Dec 23, 2025

Dec 23, 2025

Public-Private Models for Sustainable Growth

Sustainability Strategy

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Public-private collaboration is the fastest path to scale funding and align incentives for sustainable infrastructure and climate resilience.

Public-Private Models for Sustainable Growth

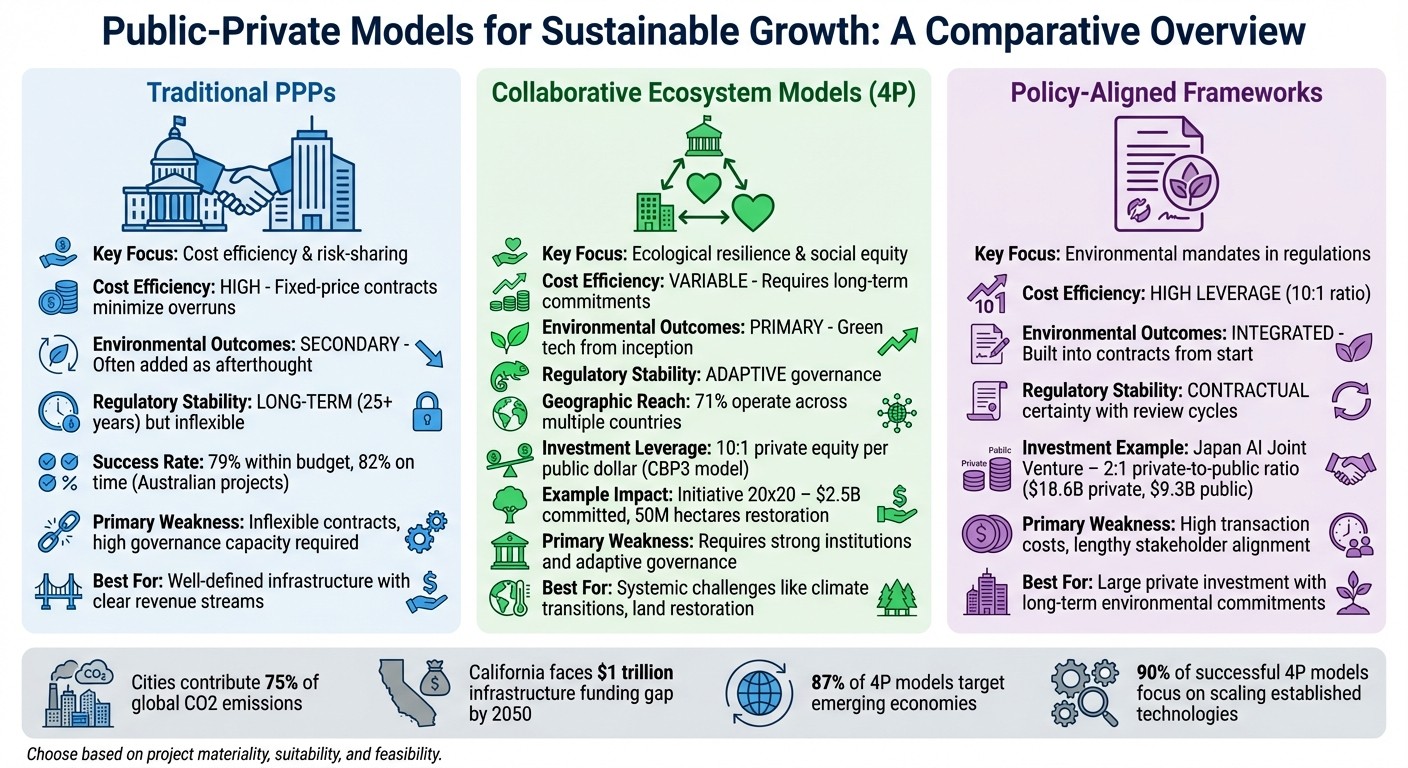

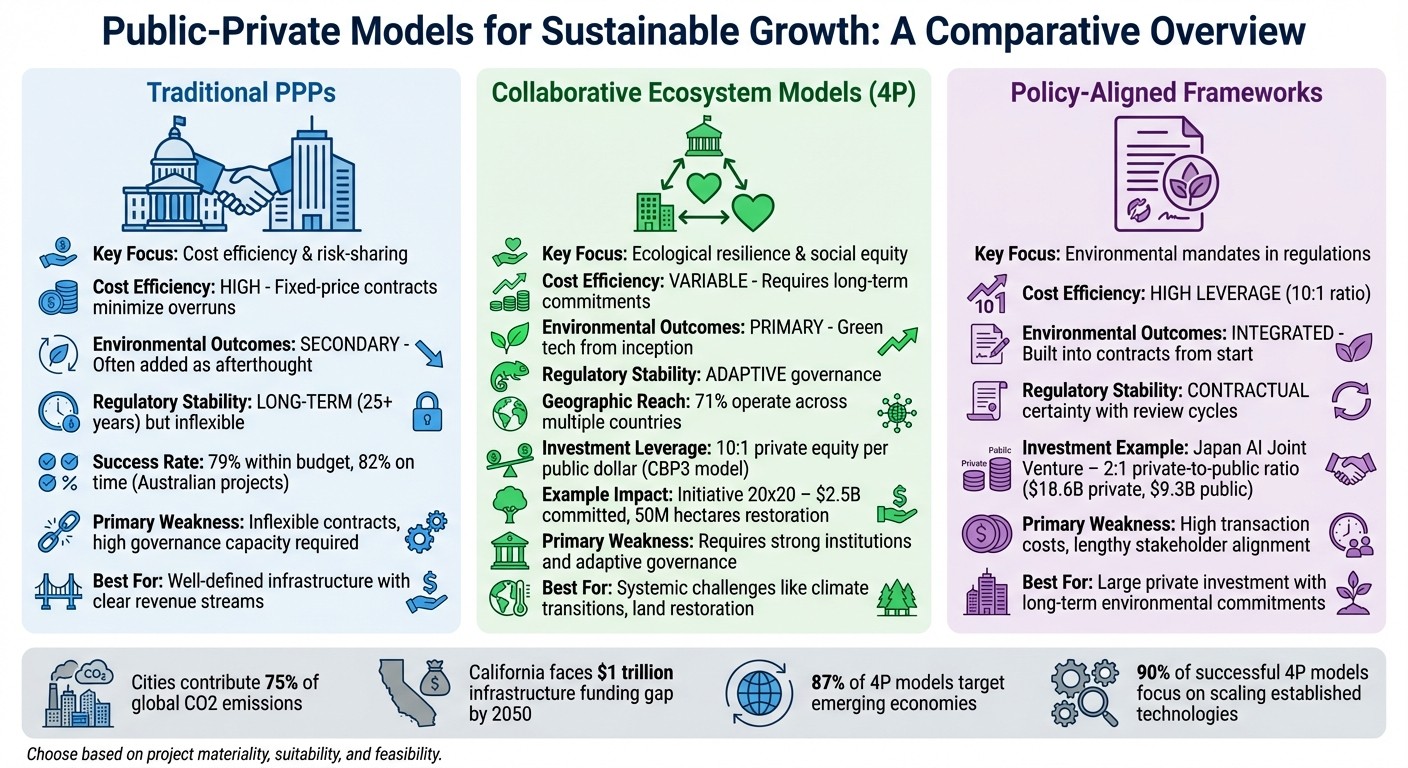

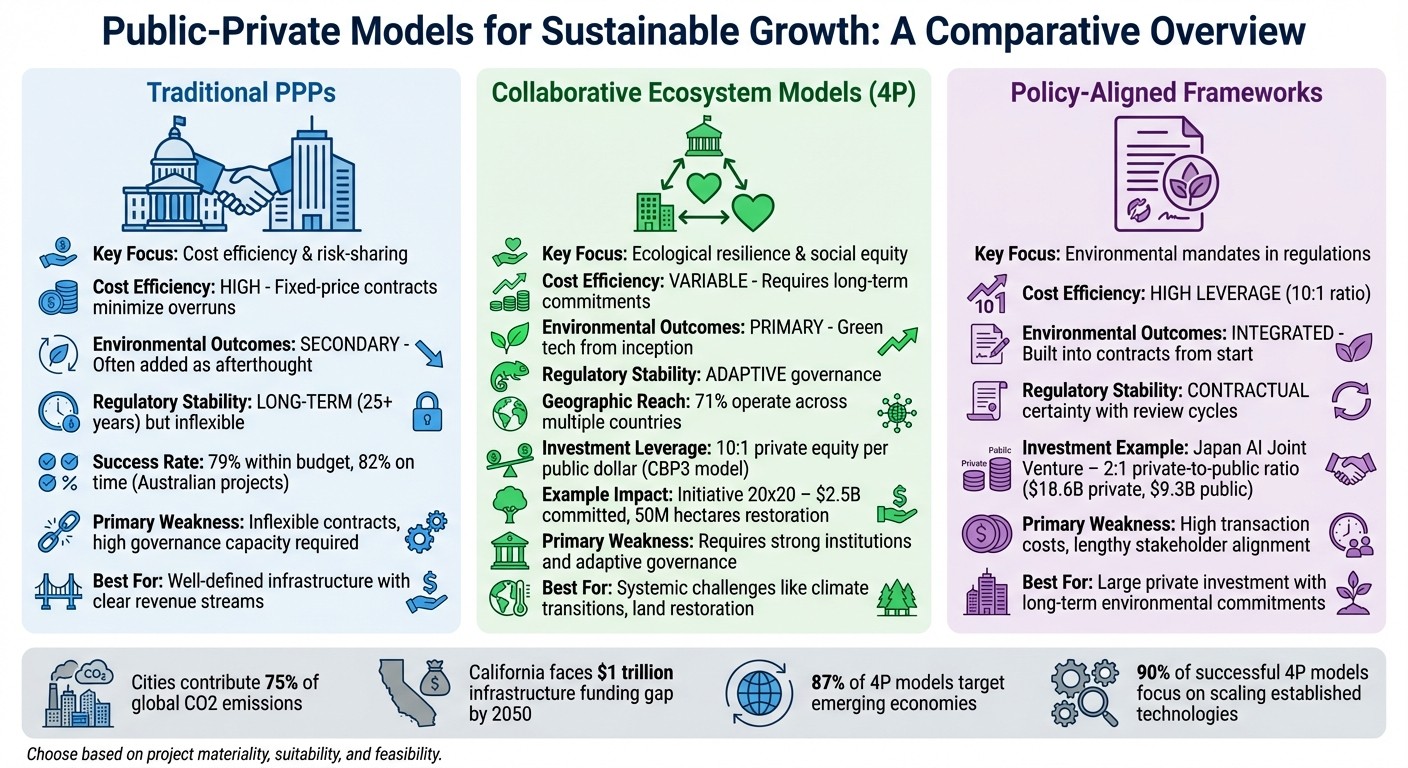

Public-private collaboration models - including PPPs, Collaborative Ecosystem Models, and Policy-Aligned Frameworks - are reshaping how governments, businesses, and philanthropic organizations address challenges like climate change and infrastructure funding gaps. These approaches combine financial resources, technical expertise, and long-term strategies to balance economic needs with environmental and social priorities.

Key Takeaways:

PPPs: Focus on cost efficiency and risk-sharing for infrastructure projects but may overlook environmental goals without specific clauses.

Collaborative Ecosystem Models: Integrate philanthropy to fund early-stage climate solutions, often addressing systemic challenges like land restoration and clean energy.

Policy-Aligned Frameworks: Embed sustainability goals directly into regulations and contracts, ensuring long-term alignment with public mandates.

Example Insights:

Cities contribute 75% of global CO2 emissions, and California faces a $1 trillion infrastructure funding gap by 2050.

Collaborative Ecosystem Models like Initiative 20x20 have committed $2.5 billion to restore 50M hectares of land.

Policy-aligned partnerships, such as Belize’s "blue bonds", leverage private investment for long-term conservation goals.

These models showcase different pathways to achieving socially responsible and economically viable outcomes, with trade-offs in cost, scalability, and stakeholder alignment.

Comparison of Three Public-Private Partnership Models for Sustainable Development

How Public-Private Partnerships can help achieve the SDGs

1. Traditional Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

Traditional Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) bring together government oversight and private-sector investment to develop infrastructure more efficiently. By assigning risks - like construction delays, operational costs, or maintenance challenges - to the party best suited to handle them, these partnerships aim to complete projects faster, stay within budget, and improve long-term outcomes compared to traditional government-led initiatives.

Each component of traditional PPPs contributes to balancing operational efficiency with broader development goals.

Resource Mobilization

One of the key strengths of traditional PPPs lies in their ability to tap into private capital, which governments often lack. For example, in fiscal year 2020, the International Finance Corporation directed $22 billion toward private companies and financial institutions in developing countries, showcasing the scale of private funding available for infrastructure projects [4].

In addition to funding, PPPs benefit from private-sector expertise, which can lead to more efficient construction and cost management [4][2]. Governments, on the other hand, provide essential non-financial contributions like land, regulatory frameworks, and research funding. They also engage local communities to align expectations and minimize delays [4].

"A successful PPP aligns private-sector practices with development priorities to deliver services that people need and can afford."

– Imad Fakhoury, Global Director, Infrastructure Finance, PPPs & Guarantees, World Bank [4]

Effective resource mobilization sets the stage for another critical element of PPP success: risk allocation.

Risk Allocation

A hallmark of traditional PPPs is their thoughtful approach to distributing risks. Risks are assigned to the party most capable of managing them [6]. For instance, construction and operational risks typically fall to private partners, while governments handle regulatory and policy-related uncertainties.

Payment structures vary based on how demand risk is managed. In user fee models, private partners collect fees or tolls directly from users, absorbing revenue uncertainty. Alternatively, availability payment models shift demand risk to the government, which pays based on whether the infrastructure meets agreed-upon performance criteria [6]. A study of PPPs in the UAE and UK identified "appropriate risk allocation" as one of the top critical factors for successful projects [7].

This strategic risk-sharing often encourages private partners to innovate, driving better performance and cost efficiency.

Innovation Transfer

Traditional PPPs often incentivize innovation by linking private-sector profits to long-term performance. Performance-based contracts encourage private companies to adopt advanced designs and life-cycle management practices that reduce maintenance costs over time. A review of Australian infrastructure projects from 1999 to 2006 found that 79% of PPP projects stayed within budget and 82% finished on time, compared to 25% and 34%, respectively, for government-led initiatives [9].

However, without specific sustainability clauses, PPPs may focus solely on efficiency without addressing environmental concerns [8]. The Hammarby Sjöstad project in Stockholm illustrates how integrating sustainability into PPPs can yield impressive results, such as a 20% reduction in waste and reliance on renewable energy [8].

Governments can further encourage innovation by requiring life-cycle cost analyses for large projects, offering predevelopment funding to strengthen agency expertise, and simplifying procurement processes [3].

Environmental Impact

Initially, traditional PPPs prioritized cost efficiency and risk management over environmental considerations [2][5]. But with global temperatures rising approximately 0.87°C (1.6°F) since the late 19th century [2], infrastructure projects must now account for their environmental impact.

"Green PPPs will thrive when backed by strong institutional frameworks, long-term financial commitments, and adaptive collaborative environments."

– Oluwatobi Mary Owojori, Department of Public Sector Finance, Tshwane University of Technology [2]

The environmental outcomes of PPPs depend heavily on contract design. When sustainability is factored into project planning, these partnerships can deliver benefits like renewable energy integration, waste reduction, and better resource efficiency. Without such provisions, PPPs risk achieving operational efficiency at the expense of broader environmental goals.

As PPP models expand globally, balancing environmental considerations with fiscal priorities becomes increasingly vital.

Scalability

The ability to replicate PPP success depends on institutional stability and governance. Countries with strong frameworks can scale these models effectively, as demonstrated by Canada, which implemented 195 PPP projects between 1990 and 2012 [8]. In contrast, weaker institutions often struggle with higher failure rates [9].

To enhance scalability, governments can establish "centers of excellence" to build expertise and streamline processes. The Wuhan East Lake Greenway project, executed under a Finance-Build-Operate-Transfer model with a $545 million investment and an 11-year concession, highlights both the potential and challenges of scaling PPPs [9].

However, scaling PPPs comes with hurdles. Each project demands rigorous legal reviews, accurate risk assessments, and coordinated stakeholder engagement. Many jurisdictions lack the technical expertise and funding required to evaluate proposals effectively [3].

When structured thoughtfully, with strong sustainability requirements and institutional support, traditional PPPs can play a pivotal role in sustainable development, balancing economic efficiency with environmental and social priorities.

2. Collaborative Ecosystem Models

Collaborative Ecosystem Models take the traditional Public-Private Partnership (PPP) structure a step further by incorporating philanthropic organizations, forming what are known as Public-Private-Philanthropic Partnerships (4P models). These partnerships blend the public sector's regulatory and policy-making capabilities, the private sector's capacity to scale solutions, and philanthropy's ability to take on higher risks over extended periods [1]. This approach helps move promising but early-stage sustainability solutions toward widespread market adoption. The following sections explore how these models expand on traditional PPP frameworks.

Resource Mobilization

In 4P models, key stakeholders - often major funders - provide the initial and long-term capital needed for solutions that are not yet commercially viable [1]. This structure addresses a critical gap, particularly in emerging economies, where 87% of 4P models are concentrated. These regions often lack the governmental capacity to implement large-scale climate solutions independently, with over 90% of these models focusing on deploying established technologies [1].

For example, the Initiative 20x20, a 4P model involving 150 partners, committed $2.5 billion in private capital to restore and protect over 50 million hectares of land in Latin America and the Caribbean, aiming for completion by 2030 [1]. Similarly, Power Africa - a U.S. government-led partnership - achieved 37.5 million new energy connections and facilitated 14,000 megawatts of clean energy projects in sub-Saharan Africa over a decade as of November 2023 [1].

"The public sector can enact policies... the private sector can establish the required business models and mobilize resources... and philanthropies can leverage their higher risk tolerance and longer time horizons."

– Hamid Samandari et al., McKinsey Sustainability [1]

These models also benefit from operating across borders, with 71% of 4P initiatives spanning multiple countries. This multinational approach allows successful strategies to be adapted to various regions. Additionally, funding sources are diversifying, with contributions from family offices, corporate foundations, and small-to-medium enterprises adding to the mix [1].

Risk Allocation

Effective risk allocation is a cornerstone of Collaborative Ecosystem Models. Unlike traditional PPPs, which assign risks to the party best equipped to handle them, these models distribute risks among sectors with varying capacities and tolerances. Philanthropic organizations often take on early-stage risks, particularly in emerging markets, while private partners manage operational and design challenges. Governments, meanwhile, provide stable regulatory frameworks to encourage long-term investments [1].

A notable example is Belize's "blue bond" debt-for-nature swap in November 2021. Facilitated by Credit Suisse and insured by the Development Finance Corporation, Belize repurchased a $553 million commercial bond at a discount, using $364 million in blue bonds. In return, the country committed to spending $4 million annually on marine conservation through 2041 [1].

This collaborative risk-sharing model has shown particular success in emerging economies. Community-Based PPPs (CBP3), a variation of these models, can leverage public funds to attract private equity at a ratio of 10:1. For instance, Prince George's County, Maryland, launched the "Clean Water Partnership" in 2015 to address stormwater management. This initiative not only met regulatory requirements but also created green jobs and supported local small businesses [10].

"A CBP3 model evolves the standard P3 contractual mechanism into a true partnership that focuses on improving water quality and a community's quality of life."

– U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [10]

Innovation Transfer

Fostering innovation is another key focus of Collaborative Ecosystem Models. These partnerships aim to help established but not yet commercially viable technologies reach a "positive tipping point" where they can sustain themselves [1]. Instead of funding basic research and development, 4P models prioritize scaling and deployment to bridge the "commercialization gap."

Global 4P models have identified 31 solution areas, accounting for roughly 30% of global emissions and land use [1]. By focusing on large-scale solutions, these models accelerate innovation in areas such as renewable energy, sustainable mobility, and land conservation.

One effective strategy involves selecting private partners early based on qualifications rather than fixed bids. This method allows for collaborative design processes and the integration of advanced technologies that traditional procurement methods might overlook [3]. Public agencies are increasingly open to unsolicited proposals, enabling them to access innovations that internal teams may not develop [3].

Organizations like Council Fire play a crucial role in aligning stakeholder goals, translating sustainability objectives into actionable plans, and ensuring that innovation transfer benefits both environmental and community needs. Their approach helps partners move beyond compliance-driven projects to create transformative, long-lasting solutions.

Environmental Impact

From the outset, Collaborative Ecosystem Models prioritize environmental outcomes, focusing on challenges like climate stability, biodiversity protection, forest conservation, and water security [1]. Unlike traditional PPPs, which initially emphasized cost efficiency and later added environmental considerations, these models integrate sustainability as a core objective.

Urban green infrastructure offers a clear example of these efforts. Cities like Vienna boast 120 square meters of green space per capita, while Lagos, Nigeria, has less than 3% of its urban area designated as green space [2]. In Accra, Ghana, green cover plummeted from 41% to 15% between 1991 and 2018, highlighting the urgent need for intervention [2].

These "resilience partnerships" go beyond individual projects to address systemic risks, such as infrastructure vulnerabilities to climate shocks. By adopting integrated strategies, these models tackle interconnected environmental, social, and economic challenges.

"Green PPPs will thrive when backed by strong institutional frameworks, long-term financial commitments, and adaptive collaborative environments."

– Oluwatobi Mary Owojori, Department of Public Sector Finance, Tshwane University of Technology [2]

Scalability

The multinational nature of 4P models - 71% operate across multiple countries - makes them well-suited for replication [1]. Scalability hinges on the presence of anchor stakeholders who provide the initial funding and the sustained momentum necessary to maintain partnerships over time. Aligning risk, return, and impact metrics among participants is also crucial to ensure smooth implementation [1].

The Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust illustrates how these models can scale effectively, even with smaller investments. This debt-for-nature swap funds ocean conservation through annual grants typically under $1 million, demonstrating the model's flexibility across varying scales [1].

A "wide tent" approach further supports scalability by uniting diverse funding sources and showcasing how climate and nature solutions contribute to broader goals like health and poverty alleviation. This strategy not only broadens the funding pool but also garners community support, stabilizing revenue streams and minimizing project delays [1][4]. States can enhance scalability by creating "centers of excellence" to provide standardized documents and facilitate skills transfer, simplifying the management of multi-stakeholder partnerships [3]. These practices strengthen collaboration between public and private sectors, paving the way for more cohesive and impactful frameworks.

3. Policy-Aligned Partnership Frameworks

Policy-Aligned Partnership Frameworks are reshaping how governments, businesses, and philanthropic organizations collaborate to meet sustainability goals. Unlike traditional public-private partnerships (PPPs) that often focus on cost efficiency, these frameworks embed environmental priorities directly into contracts and regulations. By doing so, they ensure that private sector innovation aligns with public mandates from the start, creating a stable foundation for sustainable development. This approach incorporates environmental standards from the very beginning of projects, building on earlier strategies for resource management and risk sharing.

Resource Mobilization

In policy-aligned frameworks, funding is closely tied to regulatory clarity. Governments provide incentives and establish regulations, private companies scale solutions, and philanthropic organizations contribute high-risk capital for early-stage projects. This coordinated approach addresses the challenge that 87% of current 4P models target emerging economies, where governments often lack the capacity to implement large-scale climate solutions independently [1].

A notable example of resource mobilization is Japan's AI Joint Venture. Starting in fiscal year 2026, Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) plans to invest 1 trillion yen (about $9.3 billion) over five years, while SoftBank will contribute 2 trillion yen (approximately $18.6 billion) to build data centers in Hokkaido and Osaka. This partnership, which includes Preferred Networks, aims to develop advanced AI models with 1 trillion parameters [12]. The funding structure reflects a 2:1 private-to-public investment ratio, showcasing how policy alignment can drive significant collaboration.

"The 4P model... can also be effective in advanced economies. Breathe London, whose pilot was funded by the Clean Air Fund, aims to improve air quality in the city of London." – McKinsey Sustainability Report [1]

The potential for impact is immense. Across 31 identified solution areas - spanning sectors like power generation, agriculture, and land conservation - these models address approximately 30% of global emissions and 30% of the planet's land area [1]. In California, for instance, the infrastructure funding gap is projected to hit $1 trillion by 2050 if current spending patterns persist [3].

Risk Allocation

These frameworks excel at balancing risks through performance-based contracts and full life-cycle management. Private partners handle delivery and long-term operational risks through Design-Build-Finance-Operate-Maintain (DBFOM) contracts, while governments provide stable regulatory environments to encourage investment [3]. In contrast, traditional infrastructure procurement often faces cost overruns of 10% to 20%, and sometimes even more than 100% [3].

"A successful PPP aligns private-sector practices with development priorities to deliver services that people need and can afford." – Imad Fakhoury, Global Director, Infrastructure Finance, PPPs & Guarantees, World Bank [4]

Regulatory frameworks further enhance risk-sharing. For example, Bangladesh's PPP Law of 2015 introduced clear structures for mobilizing investment and defining risk-sharing roles, creating predictability for private investors. In fiscal year 2020, the International Finance Corporation invested $22 billion in private companies and financial institutions in developing countries to leverage private-sector expertise for broader development goals [4]. These frameworks also clarify intellectual property rights, balancing the protection of proprietary innovations with public benefits.

Community engagement is another crucial element. Early involvement of labor groups, indigenous communities, and local stakeholders helps mitigate social and political risks, reducing the likelihood of delays during procurement and implementation [3][4]. Organizations like Council Fire help translate sustainability goals into actionable strategies that align environmental objectives with community needs.

Innovation Transfer

Policy-aligned frameworks accelerate the adoption of proven green technologies that have yet to achieve market viability. Instead of funding basic research, these models focus on scaling established technologies. Philanthropic capital plays a key role in de-risking early applications, allowing private partners to expand once market viability is demonstrated [1].

The Power Africa initiative exemplifies this approach. Over the decade leading up to November 2023, this U.S.-led effort brought together political leaders, private companies, and financial institutions to deliver 37.5 million new power connections and finalize financing for 14,000 megawatts of clean energy projects in sub-Saharan Africa [1].

DBFOM contracts ensure that innovations deliver long-term environmental benefits. By requiring private partners to maintain asset quality and ecological standards over 25 or more years, these agreements prioritize lasting solutions over short-term fixes [3].

"Investment in infrastructure has one of the highest economic multipliers of any form of government spending, but due to California's failure to invest in and maintain its infrastructure... the state is putting its future growth and prosperity at risk." – Bay Area Council Economic Institute [3]

Pre-competitive collaboration also supports innovation transfer in fields like AI and semiconductors. By focusing on research that benefits entire industries, these frameworks encourage competitors to pool resources for shared national priorities [11][12]. As these innovations reach commercialization, built-in environmental mandates ensure measurable sustainability outcomes.

Environmental Impact

What sets policy-aligned frameworks apart is their emphasis on environmental priorities from the outset. Unlike traditional PPPs that often add sustainability goals as an afterthought, these models integrate ecological considerations directly into contracts and regulatory requirements.

The Initiative 20x20 provides a clear example. As of September 2023, this program has gathered 150 partners and committed $2.5 billion in private funding to restore more than 50 million hectares of degraded land in Latin America and the Caribbean by 2030 [1]. By focusing explicitly on land restoration and biodiversity, the initiative has attracted diverse funding sources and ensured accountability for environmental outcomes.

"Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." – World Commission on Environment Development [2]

Resilience partnerships represent a shift toward managing systemic risks. Instead of focusing on individual projects, these frameworks address interconnected vulnerabilities to climate shocks. Strong institutional frameworks, long-term funding, and collaborative environments are essential for these partnerships to succeed [2]. Notably, 40% of climate-focused 4P models now include socioeconomic benefits like health and equity, recognizing the deep connection between environmental and social outcomes.

Scalability

The multinational nature of policy-aligned frameworks - 71% of 4P models span multiple countries - enables the replication of successful approaches [1]. This global reach allows partners to adapt proven models to different regulatory settings, cultural contexts, and resource constraints. Scalability relies on anchor stakeholders who provide initial funding and maintain momentum, as well as clear alignment on risk, return, and impact metrics [1].

Centers of excellence play a pivotal role in scaling these frameworks. By offering standardized procurement tools and facilitating knowledge transfer, these organizations reduce the complexity and costs of large partnerships. This approach empowers public agencies to engage with private entities without needing to build expertise from scratch [3]. As states adopt this model, they accelerate project pipelines while maintaining high standards across initiatives, reinforcing the integration of investment with environmental and social goals.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Building on our earlier discussion of model mechanics, let’s delve into their strengths and limitations to better understand their practical applications.

Each public-private collaboration model comes with its own set of trade-offs, influencing its effectiveness in achieving cost efficiency, environmental goals, and regulatory balance.

Traditional PPPs (Public-Private Partnerships) provide financial predictability through fixed-price contracts. While infrastructure projects often run over budget, well-structured PPPs ensure clearer cost and schedule commitments [3]. However, these models are often hindered by inflexible contracts that struggle to adapt to changing environmental demands. Additionally, they can be susceptible to opportunistic renegotiations and require a high level of governance - a resource many local governments lack [5][13].

Collaborative ecosystem models, on the other hand, focus on ecological resilience and social equity rather than just fiscal efficiency. These models integrate private sector innovation with public objectives, particularly in areas like climate action and urban sustainability [2]. A notable example is the Prince George's County Clean Water Partnership, which combines private resources for green infrastructure with the creation of green jobs and support for local small businesses [10]. However, their success hinges on adaptive governance and strong institutional frameworks, which can be challenging in weaker governance environments [2].

Policy-aligned frameworks stand out for their ability to leverage significant private investment - such as Community-Based Public-Private Partnerships (CBP3), which can attract $10 of private equity for every $1 of public funding [10]. These frameworks embed environmental priorities directly into long-term regulatory commitments, often spanning decades [3][10]. A case in point is Belize's Blue Bonds initiative, which demonstrates how these models integrate environmental mandates. However, the process of aligning diverse stakeholders, including public, private, and philanthropic entities, can lead to high transaction costs and extended timelines [1].

"PPPs are now increasingly called upon not just to deliver infrastructure, but to advance environmental outcomes and promote socio-spatial equity." – Frontiers in Sustainable Cities [2]

The table below offers a side-by-side comparison of these models across key performance dimensions:

Feature | Traditional PPPs | Collaborative Ecosystems | Policy-Aligned Frameworks |

|---|---|---|---|

Cost Efficiency | High for standard infrastructure; minimizes overruns via fixed-price contracts [3][5] | Variable; demands long-term financial commitments [2] | High leverage (10:1); reinvests savings into future projects [10] |

Environmental Outcomes | Emphasizes green technology and nature-based solutions from inception [2] | Integrates environmental mandates directly into contracts and regulations [10] | |

Regulatory Stability | Long-term contracts (25+ years) but lacks flexibility [3] | Adaptive governance; dependent on strong institutions [2] | Offers contractual certainty with mandatory review cycles [3][10] |

Primary Weakness | Inflexible contracts; requires high governance capacity [5][13] | Relies on adaptive governance; weak institutions can hinder success [2] | High transaction costs; lengthy stakeholder alignment process [1] |

These distinctions allow organizations like Council Fire to tailor specific sustainability goals to the most appropriate collaboration model. By aligning the right model with environmental and regulatory priorities, these trade-offs can be managed effectively to support sustainable development.

Conclusion

Selecting the right public-private collaboration model hinges on defining success from the outset and aligning the specific needs of your project with the strengths of each model. Traditional PPPs are particularly effective for well-defined infrastructure projects with clear revenue streams and assignable risks [14][3]. On the other hand, collaborative ecosystem models, such as 4P partnerships that include philanthropic partners, are better suited for tackling systemic challenges like climate transitions or land restoration - areas where commercial business models are still developing and require patient capital [1]. Policy-aligned frameworks stand out when significant private investment is needed alongside embedding environmental priorities into long-term regulatory commitments [1]. The key is to evaluate each approach based on its materiality, suitability, and feasibility.

When determining the best model, consider whether the initiative delivers meaningful impact, supports technology that is proven and close to market scale, and involves a committed anchor partner. Notably, over 90% of successful 4P models focus on scaling established technologies rather than early-stage innovations, highlighting that partnerships thrive when built on proven solutions [1].

"4P partnerships can make important contributions but must be carefully targeted to where they are most critically required and best suited." – McKinsey Sustainability Report [1]

These findings echo the guidance provided by Council Fire. For organizations applying this advice, choosing the right model can address challenges ranging from California's projected $1 trillion infrastructure funding gap by 2050 to implementing community-driven green infrastructure projects [3][10]. By doing so, they can transform diverse challenges into measurable environmental and social outcomes.

The most effective partnerships share a few key characteristics: they establish clear success metrics early, leverage existing frameworks instead of starting from scratch, and engage transaction-oriented advisors with a proven ability to bring complex projects to financial close [1][3]. By understanding these trade-offs, organizations can turn sustainability goals into tangible, actionable projects.

FAQs

What makes Collaborative Ecosystem Models more effective than traditional PPPs in achieving environmental goals?

Collaborative Ecosystem Models represent a step beyond the typical public-private partnership (PPP) by involving a broader mix of participants. These include corporations, NGOs, community organizations, academic institutions, and various government bodies. The emphasis here is on shared governance, setting mutual goals, and encouraging adaptive learning. This inclusive approach helps maintain alignment on sustainability targets - like cutting carbon emissions or conserving biodiversity - while embedding environmental priorities directly into decision-making processes.

On the other hand, traditional PPPs are mainly structured as contractual agreements. In these, private entities take on responsibilities such as design, construction, and operation in return for sharing risks and costs. While green PPPs can finance initiatives like renewable energy systems or water management projects, their environmental results often hinge on project-specific metrics and the robustness of the institutional framework supporting them. Collaborative Ecosystem Models, however, are better equipped to tackle intricate, multi-sector challenges that demand sustained coordination, innovation, and active community involvement. In contrast, PPPs are most effective when delivering focused infrastructure projects with well-defined financial and operational objectives.

How do philanthropic organizations contribute to public-private partnerships for sustainable growth?

Philanthropic organizations play a key role in public-private partnerships by offering flexible funding, specialized expertise, and a commitment to fairness. Their financial support, often provided through grants or non-dilutive funding, helps minimize risks for early-stage initiatives. This enables governments to take on bold policy objectives while creating opportunities for private-sector investment.

Beyond financial contributions, these organizations bring valuable knowledge and tools for assessing impact, with a strong focus on achieving social and environmental benefits. They often serve as intermediaries, helping to align the interests of diverse stakeholders, turning policy goals into practical strategies, and drawing in additional private capital. Their participation helps ensure that these partnerships balance financial, environmental, and social outcomes while aligning with broader goals for sustainability.

What makes scaling Public-Private Partnership (PPP) models challenging in emerging economies?

Scaling Public-Private Partnership (PPP) models in emerging economies comes with its fair share of hurdles. One major issue is the limited institutional capacity in these regions, which is further compounded by the absence of standardized frameworks. Variations in definitions, accounting methods, and reporting standards create a fragmented system, making it difficult to manage and assess PPPs effectively on a broader scale.

Resource constraints also play a significant role in these challenges. Many emerging economies face shortages in financial resources, technical expertise, and skilled personnel, which limits their ability to replicate successful PPP projects across different regions. Bridging these gaps is crucial for realizing the full potential of PPPs to drive meaningful and lasting development.

Related Blog Posts

Latest Articles

©2025

FAQ

FAQ

01

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

02

What makes Council Fire different?

03

Who does Council Fire you work with?

04

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

05

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

06

How does Council Fire define and measure success?

01

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

02

What makes Council Fire different?

03

Who does Council Fire you work with?

04

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

05

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

06

How does Council Fire define and measure success?

Dec 23, 2025

Public-Private Models for Sustainable Growth

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Public-private collaboration is the fastest path to scale funding and align incentives for sustainable infrastructure and climate resilience.

Public-Private Models for Sustainable Growth

Public-private collaboration models - including PPPs, Collaborative Ecosystem Models, and Policy-Aligned Frameworks - are reshaping how governments, businesses, and philanthropic organizations address challenges like climate change and infrastructure funding gaps. These approaches combine financial resources, technical expertise, and long-term strategies to balance economic needs with environmental and social priorities.

Key Takeaways:

PPPs: Focus on cost efficiency and risk-sharing for infrastructure projects but may overlook environmental goals without specific clauses.

Collaborative Ecosystem Models: Integrate philanthropy to fund early-stage climate solutions, often addressing systemic challenges like land restoration and clean energy.

Policy-Aligned Frameworks: Embed sustainability goals directly into regulations and contracts, ensuring long-term alignment with public mandates.

Example Insights:

Cities contribute 75% of global CO2 emissions, and California faces a $1 trillion infrastructure funding gap by 2050.

Collaborative Ecosystem Models like Initiative 20x20 have committed $2.5 billion to restore 50M hectares of land.

Policy-aligned partnerships, such as Belize’s "blue bonds", leverage private investment for long-term conservation goals.

These models showcase different pathways to achieving socially responsible and economically viable outcomes, with trade-offs in cost, scalability, and stakeholder alignment.

Comparison of Three Public-Private Partnership Models for Sustainable Development

How Public-Private Partnerships can help achieve the SDGs

1. Traditional Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

Traditional Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) bring together government oversight and private-sector investment to develop infrastructure more efficiently. By assigning risks - like construction delays, operational costs, or maintenance challenges - to the party best suited to handle them, these partnerships aim to complete projects faster, stay within budget, and improve long-term outcomes compared to traditional government-led initiatives.

Each component of traditional PPPs contributes to balancing operational efficiency with broader development goals.

Resource Mobilization

One of the key strengths of traditional PPPs lies in their ability to tap into private capital, which governments often lack. For example, in fiscal year 2020, the International Finance Corporation directed $22 billion toward private companies and financial institutions in developing countries, showcasing the scale of private funding available for infrastructure projects [4].

In addition to funding, PPPs benefit from private-sector expertise, which can lead to more efficient construction and cost management [4][2]. Governments, on the other hand, provide essential non-financial contributions like land, regulatory frameworks, and research funding. They also engage local communities to align expectations and minimize delays [4].

"A successful PPP aligns private-sector practices with development priorities to deliver services that people need and can afford."

– Imad Fakhoury, Global Director, Infrastructure Finance, PPPs & Guarantees, World Bank [4]

Effective resource mobilization sets the stage for another critical element of PPP success: risk allocation.

Risk Allocation

A hallmark of traditional PPPs is their thoughtful approach to distributing risks. Risks are assigned to the party most capable of managing them [6]. For instance, construction and operational risks typically fall to private partners, while governments handle regulatory and policy-related uncertainties.

Payment structures vary based on how demand risk is managed. In user fee models, private partners collect fees or tolls directly from users, absorbing revenue uncertainty. Alternatively, availability payment models shift demand risk to the government, which pays based on whether the infrastructure meets agreed-upon performance criteria [6]. A study of PPPs in the UAE and UK identified "appropriate risk allocation" as one of the top critical factors for successful projects [7].

This strategic risk-sharing often encourages private partners to innovate, driving better performance and cost efficiency.

Innovation Transfer

Traditional PPPs often incentivize innovation by linking private-sector profits to long-term performance. Performance-based contracts encourage private companies to adopt advanced designs and life-cycle management practices that reduce maintenance costs over time. A review of Australian infrastructure projects from 1999 to 2006 found that 79% of PPP projects stayed within budget and 82% finished on time, compared to 25% and 34%, respectively, for government-led initiatives [9].

However, without specific sustainability clauses, PPPs may focus solely on efficiency without addressing environmental concerns [8]. The Hammarby Sjöstad project in Stockholm illustrates how integrating sustainability into PPPs can yield impressive results, such as a 20% reduction in waste and reliance on renewable energy [8].

Governments can further encourage innovation by requiring life-cycle cost analyses for large projects, offering predevelopment funding to strengthen agency expertise, and simplifying procurement processes [3].

Environmental Impact

Initially, traditional PPPs prioritized cost efficiency and risk management over environmental considerations [2][5]. But with global temperatures rising approximately 0.87°C (1.6°F) since the late 19th century [2], infrastructure projects must now account for their environmental impact.

"Green PPPs will thrive when backed by strong institutional frameworks, long-term financial commitments, and adaptive collaborative environments."

– Oluwatobi Mary Owojori, Department of Public Sector Finance, Tshwane University of Technology [2]

The environmental outcomes of PPPs depend heavily on contract design. When sustainability is factored into project planning, these partnerships can deliver benefits like renewable energy integration, waste reduction, and better resource efficiency. Without such provisions, PPPs risk achieving operational efficiency at the expense of broader environmental goals.

As PPP models expand globally, balancing environmental considerations with fiscal priorities becomes increasingly vital.

Scalability

The ability to replicate PPP success depends on institutional stability and governance. Countries with strong frameworks can scale these models effectively, as demonstrated by Canada, which implemented 195 PPP projects between 1990 and 2012 [8]. In contrast, weaker institutions often struggle with higher failure rates [9].

To enhance scalability, governments can establish "centers of excellence" to build expertise and streamline processes. The Wuhan East Lake Greenway project, executed under a Finance-Build-Operate-Transfer model with a $545 million investment and an 11-year concession, highlights both the potential and challenges of scaling PPPs [9].

However, scaling PPPs comes with hurdles. Each project demands rigorous legal reviews, accurate risk assessments, and coordinated stakeholder engagement. Many jurisdictions lack the technical expertise and funding required to evaluate proposals effectively [3].

When structured thoughtfully, with strong sustainability requirements and institutional support, traditional PPPs can play a pivotal role in sustainable development, balancing economic efficiency with environmental and social priorities.

2. Collaborative Ecosystem Models

Collaborative Ecosystem Models take the traditional Public-Private Partnership (PPP) structure a step further by incorporating philanthropic organizations, forming what are known as Public-Private-Philanthropic Partnerships (4P models). These partnerships blend the public sector's regulatory and policy-making capabilities, the private sector's capacity to scale solutions, and philanthropy's ability to take on higher risks over extended periods [1]. This approach helps move promising but early-stage sustainability solutions toward widespread market adoption. The following sections explore how these models expand on traditional PPP frameworks.

Resource Mobilization

In 4P models, key stakeholders - often major funders - provide the initial and long-term capital needed for solutions that are not yet commercially viable [1]. This structure addresses a critical gap, particularly in emerging economies, where 87% of 4P models are concentrated. These regions often lack the governmental capacity to implement large-scale climate solutions independently, with over 90% of these models focusing on deploying established technologies [1].

For example, the Initiative 20x20, a 4P model involving 150 partners, committed $2.5 billion in private capital to restore and protect over 50 million hectares of land in Latin America and the Caribbean, aiming for completion by 2030 [1]. Similarly, Power Africa - a U.S. government-led partnership - achieved 37.5 million new energy connections and facilitated 14,000 megawatts of clean energy projects in sub-Saharan Africa over a decade as of November 2023 [1].

"The public sector can enact policies... the private sector can establish the required business models and mobilize resources... and philanthropies can leverage their higher risk tolerance and longer time horizons."

– Hamid Samandari et al., McKinsey Sustainability [1]

These models also benefit from operating across borders, with 71% of 4P initiatives spanning multiple countries. This multinational approach allows successful strategies to be adapted to various regions. Additionally, funding sources are diversifying, with contributions from family offices, corporate foundations, and small-to-medium enterprises adding to the mix [1].

Risk Allocation

Effective risk allocation is a cornerstone of Collaborative Ecosystem Models. Unlike traditional PPPs, which assign risks to the party best equipped to handle them, these models distribute risks among sectors with varying capacities and tolerances. Philanthropic organizations often take on early-stage risks, particularly in emerging markets, while private partners manage operational and design challenges. Governments, meanwhile, provide stable regulatory frameworks to encourage long-term investments [1].

A notable example is Belize's "blue bond" debt-for-nature swap in November 2021. Facilitated by Credit Suisse and insured by the Development Finance Corporation, Belize repurchased a $553 million commercial bond at a discount, using $364 million in blue bonds. In return, the country committed to spending $4 million annually on marine conservation through 2041 [1].

This collaborative risk-sharing model has shown particular success in emerging economies. Community-Based PPPs (CBP3), a variation of these models, can leverage public funds to attract private equity at a ratio of 10:1. For instance, Prince George's County, Maryland, launched the "Clean Water Partnership" in 2015 to address stormwater management. This initiative not only met regulatory requirements but also created green jobs and supported local small businesses [10].

"A CBP3 model evolves the standard P3 contractual mechanism into a true partnership that focuses on improving water quality and a community's quality of life."

– U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [10]

Innovation Transfer

Fostering innovation is another key focus of Collaborative Ecosystem Models. These partnerships aim to help established but not yet commercially viable technologies reach a "positive tipping point" where they can sustain themselves [1]. Instead of funding basic research and development, 4P models prioritize scaling and deployment to bridge the "commercialization gap."

Global 4P models have identified 31 solution areas, accounting for roughly 30% of global emissions and land use [1]. By focusing on large-scale solutions, these models accelerate innovation in areas such as renewable energy, sustainable mobility, and land conservation.

One effective strategy involves selecting private partners early based on qualifications rather than fixed bids. This method allows for collaborative design processes and the integration of advanced technologies that traditional procurement methods might overlook [3]. Public agencies are increasingly open to unsolicited proposals, enabling them to access innovations that internal teams may not develop [3].

Organizations like Council Fire play a crucial role in aligning stakeholder goals, translating sustainability objectives into actionable plans, and ensuring that innovation transfer benefits both environmental and community needs. Their approach helps partners move beyond compliance-driven projects to create transformative, long-lasting solutions.

Environmental Impact

From the outset, Collaborative Ecosystem Models prioritize environmental outcomes, focusing on challenges like climate stability, biodiversity protection, forest conservation, and water security [1]. Unlike traditional PPPs, which initially emphasized cost efficiency and later added environmental considerations, these models integrate sustainability as a core objective.

Urban green infrastructure offers a clear example of these efforts. Cities like Vienna boast 120 square meters of green space per capita, while Lagos, Nigeria, has less than 3% of its urban area designated as green space [2]. In Accra, Ghana, green cover plummeted from 41% to 15% between 1991 and 2018, highlighting the urgent need for intervention [2].

These "resilience partnerships" go beyond individual projects to address systemic risks, such as infrastructure vulnerabilities to climate shocks. By adopting integrated strategies, these models tackle interconnected environmental, social, and economic challenges.

"Green PPPs will thrive when backed by strong institutional frameworks, long-term financial commitments, and adaptive collaborative environments."

– Oluwatobi Mary Owojori, Department of Public Sector Finance, Tshwane University of Technology [2]

Scalability

The multinational nature of 4P models - 71% operate across multiple countries - makes them well-suited for replication [1]. Scalability hinges on the presence of anchor stakeholders who provide the initial funding and the sustained momentum necessary to maintain partnerships over time. Aligning risk, return, and impact metrics among participants is also crucial to ensure smooth implementation [1].

The Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust illustrates how these models can scale effectively, even with smaller investments. This debt-for-nature swap funds ocean conservation through annual grants typically under $1 million, demonstrating the model's flexibility across varying scales [1].

A "wide tent" approach further supports scalability by uniting diverse funding sources and showcasing how climate and nature solutions contribute to broader goals like health and poverty alleviation. This strategy not only broadens the funding pool but also garners community support, stabilizing revenue streams and minimizing project delays [1][4]. States can enhance scalability by creating "centers of excellence" to provide standardized documents and facilitate skills transfer, simplifying the management of multi-stakeholder partnerships [3]. These practices strengthen collaboration between public and private sectors, paving the way for more cohesive and impactful frameworks.

3. Policy-Aligned Partnership Frameworks

Policy-Aligned Partnership Frameworks are reshaping how governments, businesses, and philanthropic organizations collaborate to meet sustainability goals. Unlike traditional public-private partnerships (PPPs) that often focus on cost efficiency, these frameworks embed environmental priorities directly into contracts and regulations. By doing so, they ensure that private sector innovation aligns with public mandates from the start, creating a stable foundation for sustainable development. This approach incorporates environmental standards from the very beginning of projects, building on earlier strategies for resource management and risk sharing.

Resource Mobilization

In policy-aligned frameworks, funding is closely tied to regulatory clarity. Governments provide incentives and establish regulations, private companies scale solutions, and philanthropic organizations contribute high-risk capital for early-stage projects. This coordinated approach addresses the challenge that 87% of current 4P models target emerging economies, where governments often lack the capacity to implement large-scale climate solutions independently [1].

A notable example of resource mobilization is Japan's AI Joint Venture. Starting in fiscal year 2026, Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) plans to invest 1 trillion yen (about $9.3 billion) over five years, while SoftBank will contribute 2 trillion yen (approximately $18.6 billion) to build data centers in Hokkaido and Osaka. This partnership, which includes Preferred Networks, aims to develop advanced AI models with 1 trillion parameters [12]. The funding structure reflects a 2:1 private-to-public investment ratio, showcasing how policy alignment can drive significant collaboration.

"The 4P model... can also be effective in advanced economies. Breathe London, whose pilot was funded by the Clean Air Fund, aims to improve air quality in the city of London." – McKinsey Sustainability Report [1]

The potential for impact is immense. Across 31 identified solution areas - spanning sectors like power generation, agriculture, and land conservation - these models address approximately 30% of global emissions and 30% of the planet's land area [1]. In California, for instance, the infrastructure funding gap is projected to hit $1 trillion by 2050 if current spending patterns persist [3].

Risk Allocation

These frameworks excel at balancing risks through performance-based contracts and full life-cycle management. Private partners handle delivery and long-term operational risks through Design-Build-Finance-Operate-Maintain (DBFOM) contracts, while governments provide stable regulatory environments to encourage investment [3]. In contrast, traditional infrastructure procurement often faces cost overruns of 10% to 20%, and sometimes even more than 100% [3].

"A successful PPP aligns private-sector practices with development priorities to deliver services that people need and can afford." – Imad Fakhoury, Global Director, Infrastructure Finance, PPPs & Guarantees, World Bank [4]

Regulatory frameworks further enhance risk-sharing. For example, Bangladesh's PPP Law of 2015 introduced clear structures for mobilizing investment and defining risk-sharing roles, creating predictability for private investors. In fiscal year 2020, the International Finance Corporation invested $22 billion in private companies and financial institutions in developing countries to leverage private-sector expertise for broader development goals [4]. These frameworks also clarify intellectual property rights, balancing the protection of proprietary innovations with public benefits.

Community engagement is another crucial element. Early involvement of labor groups, indigenous communities, and local stakeholders helps mitigate social and political risks, reducing the likelihood of delays during procurement and implementation [3][4]. Organizations like Council Fire help translate sustainability goals into actionable strategies that align environmental objectives with community needs.

Innovation Transfer

Policy-aligned frameworks accelerate the adoption of proven green technologies that have yet to achieve market viability. Instead of funding basic research, these models focus on scaling established technologies. Philanthropic capital plays a key role in de-risking early applications, allowing private partners to expand once market viability is demonstrated [1].

The Power Africa initiative exemplifies this approach. Over the decade leading up to November 2023, this U.S.-led effort brought together political leaders, private companies, and financial institutions to deliver 37.5 million new power connections and finalize financing for 14,000 megawatts of clean energy projects in sub-Saharan Africa [1].

DBFOM contracts ensure that innovations deliver long-term environmental benefits. By requiring private partners to maintain asset quality and ecological standards over 25 or more years, these agreements prioritize lasting solutions over short-term fixes [3].

"Investment in infrastructure has one of the highest economic multipliers of any form of government spending, but due to California's failure to invest in and maintain its infrastructure... the state is putting its future growth and prosperity at risk." – Bay Area Council Economic Institute [3]

Pre-competitive collaboration also supports innovation transfer in fields like AI and semiconductors. By focusing on research that benefits entire industries, these frameworks encourage competitors to pool resources for shared national priorities [11][12]. As these innovations reach commercialization, built-in environmental mandates ensure measurable sustainability outcomes.

Environmental Impact

What sets policy-aligned frameworks apart is their emphasis on environmental priorities from the outset. Unlike traditional PPPs that often add sustainability goals as an afterthought, these models integrate ecological considerations directly into contracts and regulatory requirements.

The Initiative 20x20 provides a clear example. As of September 2023, this program has gathered 150 partners and committed $2.5 billion in private funding to restore more than 50 million hectares of degraded land in Latin America and the Caribbean by 2030 [1]. By focusing explicitly on land restoration and biodiversity, the initiative has attracted diverse funding sources and ensured accountability for environmental outcomes.

"Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." – World Commission on Environment Development [2]

Resilience partnerships represent a shift toward managing systemic risks. Instead of focusing on individual projects, these frameworks address interconnected vulnerabilities to climate shocks. Strong institutional frameworks, long-term funding, and collaborative environments are essential for these partnerships to succeed [2]. Notably, 40% of climate-focused 4P models now include socioeconomic benefits like health and equity, recognizing the deep connection between environmental and social outcomes.

Scalability

The multinational nature of policy-aligned frameworks - 71% of 4P models span multiple countries - enables the replication of successful approaches [1]. This global reach allows partners to adapt proven models to different regulatory settings, cultural contexts, and resource constraints. Scalability relies on anchor stakeholders who provide initial funding and maintain momentum, as well as clear alignment on risk, return, and impact metrics [1].

Centers of excellence play a pivotal role in scaling these frameworks. By offering standardized procurement tools and facilitating knowledge transfer, these organizations reduce the complexity and costs of large partnerships. This approach empowers public agencies to engage with private entities without needing to build expertise from scratch [3]. As states adopt this model, they accelerate project pipelines while maintaining high standards across initiatives, reinforcing the integration of investment with environmental and social goals.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Building on our earlier discussion of model mechanics, let’s delve into their strengths and limitations to better understand their practical applications.

Each public-private collaboration model comes with its own set of trade-offs, influencing its effectiveness in achieving cost efficiency, environmental goals, and regulatory balance.

Traditional PPPs (Public-Private Partnerships) provide financial predictability through fixed-price contracts. While infrastructure projects often run over budget, well-structured PPPs ensure clearer cost and schedule commitments [3]. However, these models are often hindered by inflexible contracts that struggle to adapt to changing environmental demands. Additionally, they can be susceptible to opportunistic renegotiations and require a high level of governance - a resource many local governments lack [5][13].

Collaborative ecosystem models, on the other hand, focus on ecological resilience and social equity rather than just fiscal efficiency. These models integrate private sector innovation with public objectives, particularly in areas like climate action and urban sustainability [2]. A notable example is the Prince George's County Clean Water Partnership, which combines private resources for green infrastructure with the creation of green jobs and support for local small businesses [10]. However, their success hinges on adaptive governance and strong institutional frameworks, which can be challenging in weaker governance environments [2].

Policy-aligned frameworks stand out for their ability to leverage significant private investment - such as Community-Based Public-Private Partnerships (CBP3), which can attract $10 of private equity for every $1 of public funding [10]. These frameworks embed environmental priorities directly into long-term regulatory commitments, often spanning decades [3][10]. A case in point is Belize's Blue Bonds initiative, which demonstrates how these models integrate environmental mandates. However, the process of aligning diverse stakeholders, including public, private, and philanthropic entities, can lead to high transaction costs and extended timelines [1].

"PPPs are now increasingly called upon not just to deliver infrastructure, but to advance environmental outcomes and promote socio-spatial equity." – Frontiers in Sustainable Cities [2]

The table below offers a side-by-side comparison of these models across key performance dimensions:

Feature | Traditional PPPs | Collaborative Ecosystems | Policy-Aligned Frameworks |

|---|---|---|---|

Cost Efficiency | High for standard infrastructure; minimizes overruns via fixed-price contracts [3][5] | Variable; demands long-term financial commitments [2] | High leverage (10:1); reinvests savings into future projects [10] |

Environmental Outcomes | Emphasizes green technology and nature-based solutions from inception [2] | Integrates environmental mandates directly into contracts and regulations [10] | |

Regulatory Stability | Long-term contracts (25+ years) but lacks flexibility [3] | Adaptive governance; dependent on strong institutions [2] | Offers contractual certainty with mandatory review cycles [3][10] |

Primary Weakness | Inflexible contracts; requires high governance capacity [5][13] | Relies on adaptive governance; weak institutions can hinder success [2] | High transaction costs; lengthy stakeholder alignment process [1] |

These distinctions allow organizations like Council Fire to tailor specific sustainability goals to the most appropriate collaboration model. By aligning the right model with environmental and regulatory priorities, these trade-offs can be managed effectively to support sustainable development.

Conclusion

Selecting the right public-private collaboration model hinges on defining success from the outset and aligning the specific needs of your project with the strengths of each model. Traditional PPPs are particularly effective for well-defined infrastructure projects with clear revenue streams and assignable risks [14][3]. On the other hand, collaborative ecosystem models, such as 4P partnerships that include philanthropic partners, are better suited for tackling systemic challenges like climate transitions or land restoration - areas where commercial business models are still developing and require patient capital [1]. Policy-aligned frameworks stand out when significant private investment is needed alongside embedding environmental priorities into long-term regulatory commitments [1]. The key is to evaluate each approach based on its materiality, suitability, and feasibility.

When determining the best model, consider whether the initiative delivers meaningful impact, supports technology that is proven and close to market scale, and involves a committed anchor partner. Notably, over 90% of successful 4P models focus on scaling established technologies rather than early-stage innovations, highlighting that partnerships thrive when built on proven solutions [1].

"4P partnerships can make important contributions but must be carefully targeted to where they are most critically required and best suited." – McKinsey Sustainability Report [1]

These findings echo the guidance provided by Council Fire. For organizations applying this advice, choosing the right model can address challenges ranging from California's projected $1 trillion infrastructure funding gap by 2050 to implementing community-driven green infrastructure projects [3][10]. By doing so, they can transform diverse challenges into measurable environmental and social outcomes.

The most effective partnerships share a few key characteristics: they establish clear success metrics early, leverage existing frameworks instead of starting from scratch, and engage transaction-oriented advisors with a proven ability to bring complex projects to financial close [1][3]. By understanding these trade-offs, organizations can turn sustainability goals into tangible, actionable projects.

FAQs

What makes Collaborative Ecosystem Models more effective than traditional PPPs in achieving environmental goals?

Collaborative Ecosystem Models represent a step beyond the typical public-private partnership (PPP) by involving a broader mix of participants. These include corporations, NGOs, community organizations, academic institutions, and various government bodies. The emphasis here is on shared governance, setting mutual goals, and encouraging adaptive learning. This inclusive approach helps maintain alignment on sustainability targets - like cutting carbon emissions or conserving biodiversity - while embedding environmental priorities directly into decision-making processes.

On the other hand, traditional PPPs are mainly structured as contractual agreements. In these, private entities take on responsibilities such as design, construction, and operation in return for sharing risks and costs. While green PPPs can finance initiatives like renewable energy systems or water management projects, their environmental results often hinge on project-specific metrics and the robustness of the institutional framework supporting them. Collaborative Ecosystem Models, however, are better equipped to tackle intricate, multi-sector challenges that demand sustained coordination, innovation, and active community involvement. In contrast, PPPs are most effective when delivering focused infrastructure projects with well-defined financial and operational objectives.

How do philanthropic organizations contribute to public-private partnerships for sustainable growth?

Philanthropic organizations play a key role in public-private partnerships by offering flexible funding, specialized expertise, and a commitment to fairness. Their financial support, often provided through grants or non-dilutive funding, helps minimize risks for early-stage initiatives. This enables governments to take on bold policy objectives while creating opportunities for private-sector investment.

Beyond financial contributions, these organizations bring valuable knowledge and tools for assessing impact, with a strong focus on achieving social and environmental benefits. They often serve as intermediaries, helping to align the interests of diverse stakeholders, turning policy goals into practical strategies, and drawing in additional private capital. Their participation helps ensure that these partnerships balance financial, environmental, and social outcomes while aligning with broader goals for sustainability.

What makes scaling Public-Private Partnership (PPP) models challenging in emerging economies?

Scaling Public-Private Partnership (PPP) models in emerging economies comes with its fair share of hurdles. One major issue is the limited institutional capacity in these regions, which is further compounded by the absence of standardized frameworks. Variations in definitions, accounting methods, and reporting standards create a fragmented system, making it difficult to manage and assess PPPs effectively on a broader scale.

Resource constraints also play a significant role in these challenges. Many emerging economies face shortages in financial resources, technical expertise, and skilled personnel, which limits their ability to replicate successful PPP projects across different regions. Bridging these gaps is crucial for realizing the full potential of PPPs to drive meaningful and lasting development.

Related Blog Posts

FAQ

01

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

02

What makes Council Fire different?

03

Who does Council Fire you work with?

04

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

05

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

06

How does Council Fire define and measure success?

Dec 23, 2025

Public-Private Models for Sustainable Growth

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Public-private collaboration is the fastest path to scale funding and align incentives for sustainable infrastructure and climate resilience.

Public-Private Models for Sustainable Growth

Public-private collaboration models - including PPPs, Collaborative Ecosystem Models, and Policy-Aligned Frameworks - are reshaping how governments, businesses, and philanthropic organizations address challenges like climate change and infrastructure funding gaps. These approaches combine financial resources, technical expertise, and long-term strategies to balance economic needs with environmental and social priorities.

Key Takeaways:

PPPs: Focus on cost efficiency and risk-sharing for infrastructure projects but may overlook environmental goals without specific clauses.

Collaborative Ecosystem Models: Integrate philanthropy to fund early-stage climate solutions, often addressing systemic challenges like land restoration and clean energy.

Policy-Aligned Frameworks: Embed sustainability goals directly into regulations and contracts, ensuring long-term alignment with public mandates.

Example Insights:

Cities contribute 75% of global CO2 emissions, and California faces a $1 trillion infrastructure funding gap by 2050.

Collaborative Ecosystem Models like Initiative 20x20 have committed $2.5 billion to restore 50M hectares of land.

Policy-aligned partnerships, such as Belize’s "blue bonds", leverage private investment for long-term conservation goals.

These models showcase different pathways to achieving socially responsible and economically viable outcomes, with trade-offs in cost, scalability, and stakeholder alignment.

Comparison of Three Public-Private Partnership Models for Sustainable Development

How Public-Private Partnerships can help achieve the SDGs

1. Traditional Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

Traditional Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) bring together government oversight and private-sector investment to develop infrastructure more efficiently. By assigning risks - like construction delays, operational costs, or maintenance challenges - to the party best suited to handle them, these partnerships aim to complete projects faster, stay within budget, and improve long-term outcomes compared to traditional government-led initiatives.

Each component of traditional PPPs contributes to balancing operational efficiency with broader development goals.

Resource Mobilization

One of the key strengths of traditional PPPs lies in their ability to tap into private capital, which governments often lack. For example, in fiscal year 2020, the International Finance Corporation directed $22 billion toward private companies and financial institutions in developing countries, showcasing the scale of private funding available for infrastructure projects [4].

In addition to funding, PPPs benefit from private-sector expertise, which can lead to more efficient construction and cost management [4][2]. Governments, on the other hand, provide essential non-financial contributions like land, regulatory frameworks, and research funding. They also engage local communities to align expectations and minimize delays [4].

"A successful PPP aligns private-sector practices with development priorities to deliver services that people need and can afford."

– Imad Fakhoury, Global Director, Infrastructure Finance, PPPs & Guarantees, World Bank [4]

Effective resource mobilization sets the stage for another critical element of PPP success: risk allocation.

Risk Allocation

A hallmark of traditional PPPs is their thoughtful approach to distributing risks. Risks are assigned to the party most capable of managing them [6]. For instance, construction and operational risks typically fall to private partners, while governments handle regulatory and policy-related uncertainties.

Payment structures vary based on how demand risk is managed. In user fee models, private partners collect fees or tolls directly from users, absorbing revenue uncertainty. Alternatively, availability payment models shift demand risk to the government, which pays based on whether the infrastructure meets agreed-upon performance criteria [6]. A study of PPPs in the UAE and UK identified "appropriate risk allocation" as one of the top critical factors for successful projects [7].

This strategic risk-sharing often encourages private partners to innovate, driving better performance and cost efficiency.

Innovation Transfer

Traditional PPPs often incentivize innovation by linking private-sector profits to long-term performance. Performance-based contracts encourage private companies to adopt advanced designs and life-cycle management practices that reduce maintenance costs over time. A review of Australian infrastructure projects from 1999 to 2006 found that 79% of PPP projects stayed within budget and 82% finished on time, compared to 25% and 34%, respectively, for government-led initiatives [9].

However, without specific sustainability clauses, PPPs may focus solely on efficiency without addressing environmental concerns [8]. The Hammarby Sjöstad project in Stockholm illustrates how integrating sustainability into PPPs can yield impressive results, such as a 20% reduction in waste and reliance on renewable energy [8].

Governments can further encourage innovation by requiring life-cycle cost analyses for large projects, offering predevelopment funding to strengthen agency expertise, and simplifying procurement processes [3].

Environmental Impact

Initially, traditional PPPs prioritized cost efficiency and risk management over environmental considerations [2][5]. But with global temperatures rising approximately 0.87°C (1.6°F) since the late 19th century [2], infrastructure projects must now account for their environmental impact.

"Green PPPs will thrive when backed by strong institutional frameworks, long-term financial commitments, and adaptive collaborative environments."

– Oluwatobi Mary Owojori, Department of Public Sector Finance, Tshwane University of Technology [2]

The environmental outcomes of PPPs depend heavily on contract design. When sustainability is factored into project planning, these partnerships can deliver benefits like renewable energy integration, waste reduction, and better resource efficiency. Without such provisions, PPPs risk achieving operational efficiency at the expense of broader environmental goals.

As PPP models expand globally, balancing environmental considerations with fiscal priorities becomes increasingly vital.

Scalability

The ability to replicate PPP success depends on institutional stability and governance. Countries with strong frameworks can scale these models effectively, as demonstrated by Canada, which implemented 195 PPP projects between 1990 and 2012 [8]. In contrast, weaker institutions often struggle with higher failure rates [9].

To enhance scalability, governments can establish "centers of excellence" to build expertise and streamline processes. The Wuhan East Lake Greenway project, executed under a Finance-Build-Operate-Transfer model with a $545 million investment and an 11-year concession, highlights both the potential and challenges of scaling PPPs [9].

However, scaling PPPs comes with hurdles. Each project demands rigorous legal reviews, accurate risk assessments, and coordinated stakeholder engagement. Many jurisdictions lack the technical expertise and funding required to evaluate proposals effectively [3].

When structured thoughtfully, with strong sustainability requirements and institutional support, traditional PPPs can play a pivotal role in sustainable development, balancing economic efficiency with environmental and social priorities.

2. Collaborative Ecosystem Models

Collaborative Ecosystem Models take the traditional Public-Private Partnership (PPP) structure a step further by incorporating philanthropic organizations, forming what are known as Public-Private-Philanthropic Partnerships (4P models). These partnerships blend the public sector's regulatory and policy-making capabilities, the private sector's capacity to scale solutions, and philanthropy's ability to take on higher risks over extended periods [1]. This approach helps move promising but early-stage sustainability solutions toward widespread market adoption. The following sections explore how these models expand on traditional PPP frameworks.

Resource Mobilization

In 4P models, key stakeholders - often major funders - provide the initial and long-term capital needed for solutions that are not yet commercially viable [1]. This structure addresses a critical gap, particularly in emerging economies, where 87% of 4P models are concentrated. These regions often lack the governmental capacity to implement large-scale climate solutions independently, with over 90% of these models focusing on deploying established technologies [1].

For example, the Initiative 20x20, a 4P model involving 150 partners, committed $2.5 billion in private capital to restore and protect over 50 million hectares of land in Latin America and the Caribbean, aiming for completion by 2030 [1]. Similarly, Power Africa - a U.S. government-led partnership - achieved 37.5 million new energy connections and facilitated 14,000 megawatts of clean energy projects in sub-Saharan Africa over a decade as of November 2023 [1].

"The public sector can enact policies... the private sector can establish the required business models and mobilize resources... and philanthropies can leverage their higher risk tolerance and longer time horizons."

– Hamid Samandari et al., McKinsey Sustainability [1]

These models also benefit from operating across borders, with 71% of 4P initiatives spanning multiple countries. This multinational approach allows successful strategies to be adapted to various regions. Additionally, funding sources are diversifying, with contributions from family offices, corporate foundations, and small-to-medium enterprises adding to the mix [1].

Risk Allocation