Jan 20, 2026

How to Develop a Nature-Based Solutions Strategy for Universities & Research Institutions

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Step-by-step guide for universities to plan, fund, implement, and monitor nature-based solutions—stormwater, urban greening, biodiversity, and campus resilience.

How to Develop a Nature-Based Solutions Strategy for Universities & Research Institutions

Universities can lead the way in addressing environmental challenges by integrating Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) into their campuses. These approaches use natural systems like rain gardens, bioswales, and urban forests to manage issues such as stormwater, heat, and biodiversity loss. Beyond ecological benefits, NbS can improve campus operations, create learning opportunities, and align with sustainability goals.

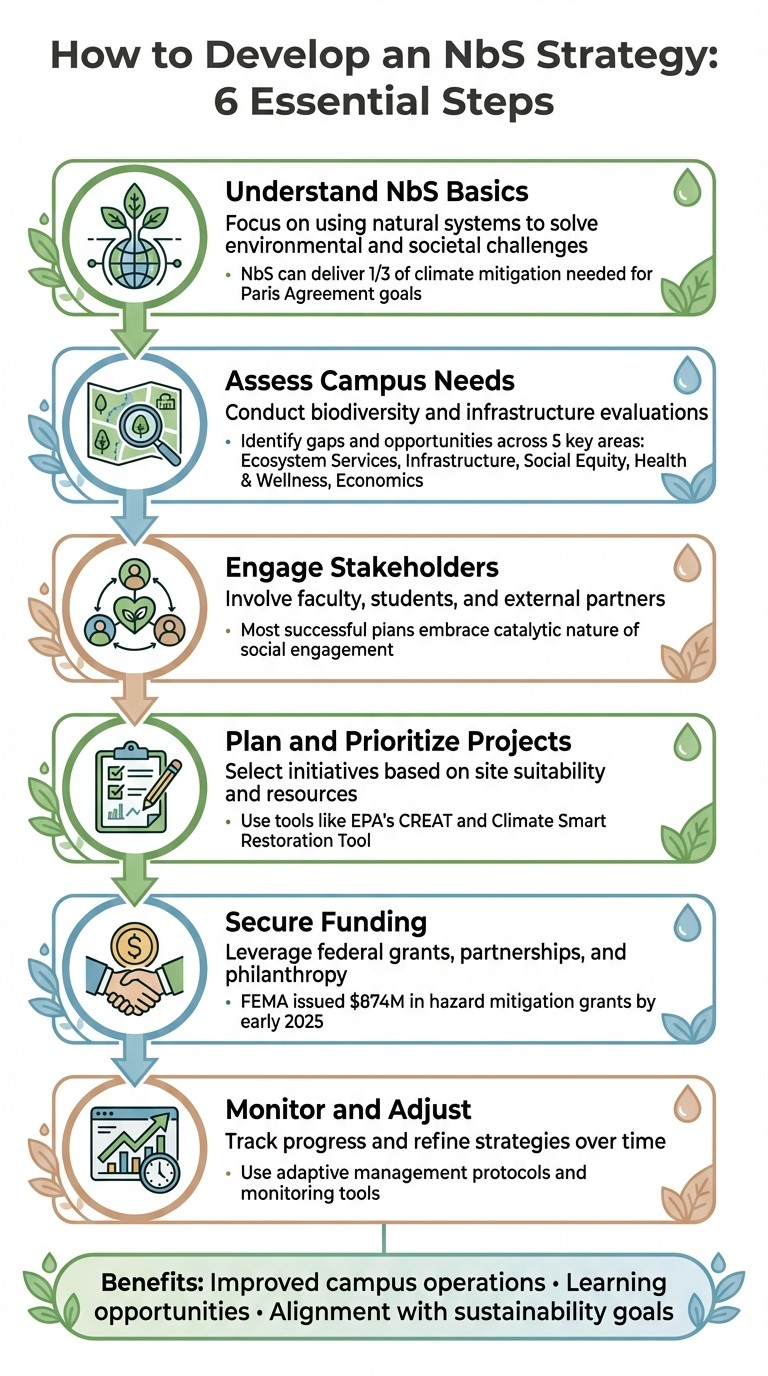

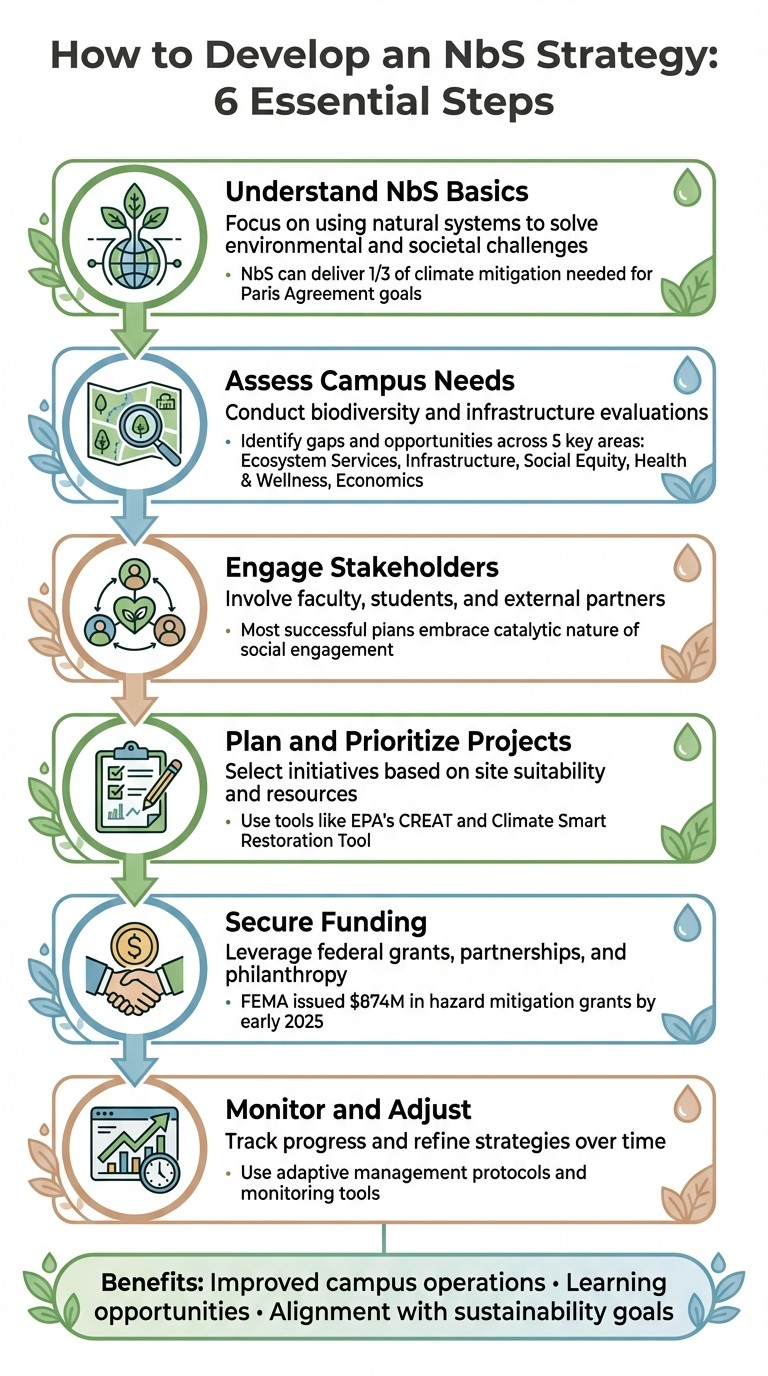

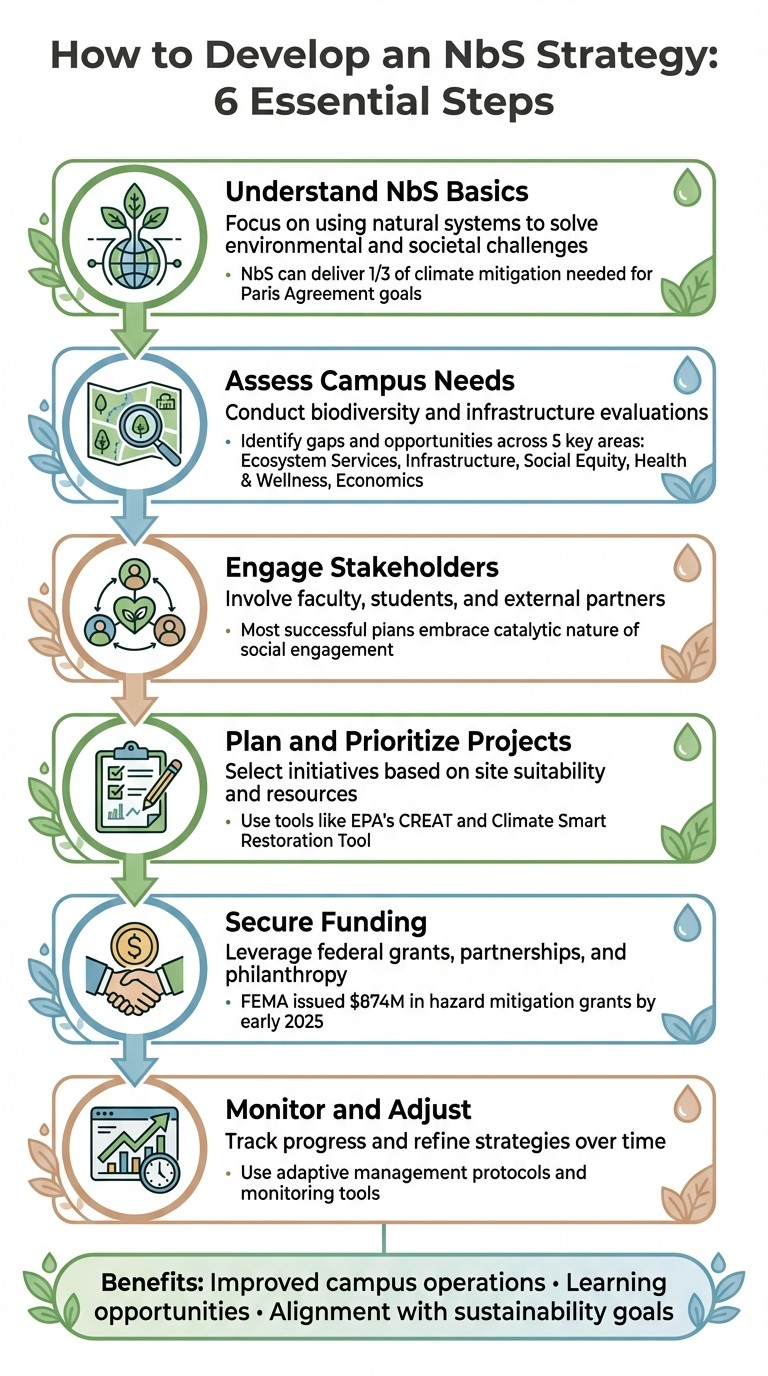

Key steps to develop an NbS strategy:

Understand NbS Basics: Focus on using natural systems to solve environmental and societal challenges.

Assess Campus Needs: Conduct biodiversity and infrastructure evaluations to identify gaps and opportunities.

Engage Stakeholders: Involve faculty, students, and external partners in planning and implementation.

Plan and Prioritize Projects: Select initiatives based on site suitability, resources, and long-term maintenance.

Secure Funding: Leverage federal grants, partnerships, and philanthropic contributions to support projects.

Monitor and Adjust: Use tools and metrics to track progress and refine strategies over time.

6-Step Process for Developing Nature-Based Solutions Strategy at Universities

Understanding Nature-Based Solutions Basics

What Are Nature-Based Solutions?

Nature-based solutions (NbS) focus on protecting, managing, and restoring natural and managed ecosystems to tackle societal challenges while benefiting both people and the environment [1][8]. Unlike traditional gray infrastructure, NbS use natural systems such as rain gardens or urban forests to address environmental needs effectively.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) succinctly explains:

"Nature-based solutions leverage nature and the power of healthy ecosystems to protect people, optimise infrastructure and safeguard a stable and biodiverse future." [8]

These approaches offer more than just functionality - they provide multiple benefits. For example, a bioswale on campus not only manages stormwater runoff but also supports wildlife habitats, reduces flood risks, and creates green spaces for students to enjoy. On a global scale, NbS are powerful tools. They could deliver about one-third of the climate mitigation required to meet the Paris Agreement goals, with ecosystem services valued at $170 billion annually [8]. Specific measures, like mangroves, prevent approximately $57 billion in flood damages each year, including in the United States [8].

This foundational understanding highlights the importance of applying guiding principles to integrate NbS effectively into campus planning.

Core Principles of NbS for Universities

For universities to successfully implement NbS, they need to follow key principles. Solutions should aim for net positive biodiversity outcomes and be designed to address future climate conditions. For instance, selecting tree species that can thrive in warmer climates or placing wetlands strategically to handle stronger storms ensures long-term success.

Equity and community involvement are equally vital. Katie Warnell from the Nicholas Institute emphasizes that while many institutions already use NbS strategies, they often miss opportunities to maximize their impact:

"While [institutions] already use many of the strategies included in the Roadmap, these projects are not always designed using a nature-based solutions framing. The approaches and information in the Roadmap can help expand value to both people and nature." [7]

This underscores the importance of engaging students, faculty, staff, and nearby communities in planning efforts. Incorporating Indigenous Knowledges when appropriate and ensuring projects serve all groups equitably are also essential steps [1][7]. Additionally, universities should treat natural systems as infrastructure, not just as decorative landscaping. For example, a healthy riparian buffer along a campus stream offers critical services like erosion control and water filtration. By embedding these principles into campus planning, NbS can function as essential infrastructure.

Finally, adaptive management is crucial. Regular monitoring allows universities to assess project performance and make necessary adjustments based on collected data and evolving conditions [1].

NbS Strategy | Campus Application | Primary Environmental Benefit |

|---|---|---|

Bioretention | Rain gardens, bioswales | Manages stormwater and runoff |

Urban Greening | Campus forests, tree planting | Reduces heat and supports human health |

Riparian Restoration | Stream buffer zones | Improves water quality and prevents erosion |

Permeable Pavement | Parking lots, walkways | Minimizes flooding and runoff |

Ecosystem Restoration | Wetland or meadow restoration | Enhances biodiversity and captures carbon |

Assessing Your Institution's Needs and Resources

Conduct Environmental and Biodiversity Assessments

Before launching Nature-based Solutions (NbS) projects, it’s essential to evaluate your campus's current environmental conditions and resilience. According to Second Nature, resilience is shaped by unique local factors, including specific goals, capacities, and vulnerabilities [9]. Start with a comprehensive environmental and biodiversity assessment that examines five key areas: Ecosystem Services, Infrastructure (both traditional and green systems), Social Equity & Governance, Health & Wellness, and Economic considerations [9].

Take a close look at how existing wetlands, forests, and green spaces perform. Do these areas effectively manage stormwater runoff, provide cooling during heat waves, or support local biodiversity? These insights can help identify where natural systems could replace or complement traditional engineered solutions [1]. Incorporate adaptive management strategies that continuously monitor these natural systems, and involve diverse stakeholders - faculty, students, facilities staff, and community members. As Second Nature highlights:

"the most successful plans embrace the catalytic nature of social engagement" [9]

This process will help uncover campus-specific challenges and opportunities for enhancing resilience.

Identify Campus-Specific Challenges and Opportunities

Once you’ve established a baseline assessment, focus on identifying the unique challenges and opportunities your campus faces. Tools like asset mapping can go beyond physical infrastructure to include faculty expertise, student participation, financial resources, and partnerships with the surrounding community [10].

Use methods such as SWOT analysis and visioning exercises to explore potential scenarios for the coming decades. These activities can help balance broader priorities - like advancing research or increasing student diversity - with climate-related goals [10]. Sometimes, these sessions reveal unexpected opportunities. For instance, unused parking lots could be transformed into bioswales, or neglected stream corridors might be restored to serve as outdoor classrooms. Seek out projects that offer multiple benefits, such as green roofs that reduce stormwater runoff, lower cooling costs, and create habitats for wildlife [1].

To ensure these efforts are sustainable and not just one-off initiatives, integrate NbS objectives into your institution’s long-term plans. Align them with 5-year budgets and 10-year master plans, embedding these strategies into the broader framework [10]. Focus on high-impact, low-cost projects, such as LED lighting upgrades, which can save over $1,000,000 annually while reducing energy use by 25% [10]. By doing so, you can make NbS a lasting part of your institution's development.

Engaging Stakeholders for Collaborative NbS Development

Internal Stakeholder Collaboration

Developing an effective Nature-based Solutions (NbS) strategy depends on the active involvement of internal stakeholders such as faculty, students, and administrative staff. Faculty often take on roles as technical experts and project leaders, guiding the scientific and practical aspects of initiatives. Meanwhile, students can contribute as researchers and even co-authors on institutional plans, gaining valuable hands-on experience. Administrative staff, on the other hand, ensure the smooth execution of day-to-day operations, bridging the gap between planning and implementation.

Take the example of Duke University, where a faculty-led team crafted the DOI Nature-Based Solutions Roadmap in December 2023. This roadmap outlined 29 different NbS strategies and included over 400 case studies. As Katie Warnell explained:

"The approaches and information in the Roadmap can help expand value to both people and nature." [7]

To deepen engagement, institutions can integrate green infrastructure projects into their academic curriculum, offering students opportunities to gain professional skills while contributing to sustainability goals. Establishing specialized research hubs, such as a Wetland Center or campus-focused restoration programs, can further centralize efforts and encourage collaboration on specific themes. These initiatives not only enhance learning but also create a cohesive internal framework that can be expanded through external collaborations.

Building Partnerships with External Organizations

While internal collaboration lays the groundwork, partnerships with external organizations significantly broaden the impact and reach of NbS strategies. Collaborating with federal, state, and local governments, nonprofits, tribal groups, community organizations, and private sector entities brings together diverse expertise in fields like ecology, engineering, and urban planning. This multidisciplinary approach is essential for tackling complex environmental challenges.

For instance, in September 2023, Duke University joined the Network for Engineering With Nature, a group of researchers and practitioners focused on using natural features to address U.S. infrastructure challenges. Spearheaded by the Nicholas Institute and the Pratt School of Engineering, this partnership has allowed Duke to work closely with federal agencies and other academic institutions.[7]

These external collaborations provide access to technical expertise, regulatory insights, and critical funding opportunities, significantly amplifying the benefits of NbS. Programs like FEMA's Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities initiative or the EPA's Urban Waters Small Grants offer financial support to advance such partnerships. These resources help deliver tangible outcomes, such as improved water quality and greater climate resilience, while fostering long-term, impactful solutions.

Designing and Implementing NbS Action Plans

Selecting and Prioritizing NbS Projects

After conducting campus assessments and identifying opportunities, the next step is selecting projects that align with your institution's sustainability goals. Focus on initiatives that provide clear benefits for both people and the environment. Evaluate each project based on its suitability for the site, the resources required for implementation, and the long-term maintenance it will need.

Duke University's 2023 Nature-Based Solutions Roadmap serves as a valuable guide for this process. It outlines 29 nature-based strategies and includes over 400 case studies, offering practical insights into project selection and execution. Developed by experts like Lydia Olander and Katie Warnell, the roadmap emphasizes transitioning from traditional, gray infrastructure to natural alternatives, with detailed guidance on site-specific considerations and ongoing upkeep requirements.[1][7]

When narrowing down projects, apply overarching principles such as engaging the community and incorporating Indigenous Knowledges to ensure initiatives are relevant and inclusive. Tools like the EPA's Climate Resilience Evaluation & Awareness Tool (CREAT) can help identify climate risks to campus assets, while the Climate Smart Restoration Tool aids in selecting native plants suited to future climate conditions at your location.[6]

This thoughtful selection process lays the groundwork for weaving nature-based solutions (NbS) into the fabric of campus life.

Integrating NbS into Campus Operations

To fully embrace NbS, connect these projects to both infrastructure upgrades and educational opportunities. Universities can extend the impact of "green campus" initiatives by embedding them into a "green curriculum", creating a ripple effect that reaches beyond landscaping into the institution’s academic mission.[5] This could involve incorporating green infrastructure projects into coursework, establishing research hubs like wetland labs, or updating landscaping policies to prioritize native species and ecosystem health.

Duke University provides a strong example of this integration. In September 2023, the university joined the Network for Engineering With Nature (N-EWN), a collaboration led by the Nicholas Institute and involving the Nicholas School of the Environment and the Pratt School of Engineering. This initiative brings nature-based engineering into both research and campus operations, showcasing how sustainability can be made a visible and actionable part of university life.[7] By transitioning from traditional infrastructure to natural or hybrid systems, institutions can make sustainability a core component of daily operations.

With NbS projects in place, ongoing monitoring ensures their continued success and relevance.

Using Monitoring Tools and Metrics

Once projects are implemented, consistent monitoring is critical to validate their impact and guide adjustments. Choose monitoring tools that align with your institution’s resources and the specific nature of each project. The Urban Nature Indexes (UNI) framework offers a comprehensive approach, covering 30 indicator topics across six themes: consumption drivers, human pressures, habitat status, species status, nature’s benefits to people, and governance responses.[12] For campuses with limited resources, begin with straightforward metrics like air and water quality or waste reduction, and expand to more complex indicators over time.

Visual inspection tools, such as Bioretention Illustrated, can help assess the performance of green infrastructure. Schedule periodic evaluations - every one to five years - to track ecological trends and determine whether conditions are improving, remaining steady, or declining. The DOI Nature-Based Solutions Roadmap provides links to specific monitoring tools and training resources for each of the 29 NbS strategies, offering practical support for tracking progress.[1][7]

As Lydia Olander, Program Director at Duke's Nicholas Institute, observed:

"Support for nature-based solutions is growing rapidly across the United States as a way to improve the resilience of our communities and ecosystems."[7]

This increasing momentum underscores the importance of robust monitoring to demonstrate the value of NbS and maintain institutional commitment.

Securing Funding and Ensuring Long-Term Success

Funding Mechanisms for NbS

Universities aiming to implement Nature-based Solutions (NbS) can tap into a variety of funding sources, including federal grants, public-private partnerships, green banks, and philanthropic contributions. Among these, federal grants are often the most substantial. Agencies like FEMA, the EPA, USDA, and the Department of the Interior (DOI) provide targeted support for large-scale projects. By early 2025, FEMA had already issued 119 hazard mitigation assistance sub-grants, totaling $874 million for disaster relief and mitigation efforts [2]. The DOI, which oversees more than 480 million acres of federal lands, is a key collaborator for expansive NbS initiatives [7].

Public-private partnerships offer an opportunity to pool resources while sharing risks and expertise among government, nonprofit, and private entities. These partnerships can bring innovative solutions but often require careful alignment of interests. On the other hand, green banks and community lenders provide long-term capital for projects that fall outside traditional grant cycles [7]. For smaller, research-focused efforts, philanthropic contributions offer flexibility, especially for pilot programs and initiatives that may not meet standard funding criteria [11].

To improve the chances of securing funding, universities should form cross-disciplinary teams, bringing together ecologists, engineers, planners, and other experts. These teams can craft compelling grant proposals that appeal to multiple funding sources [11].

Funding Source | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

Federal Grants (FEMA, EPA, USDA) | High funding potential; supports large-scale infrastructure [11] | Competitive process; strict reporting requirements [11] | Large projects like flood prevention or watershed restoration |

Public-Private Partnerships | Shared financial risk; access to private sector expertise [11] | Complex legal arrangements; requires aligned goals | Urban infrastructure or community-university collaborations |

Philanthropic Contributions | Flexible funding; ideal for pilot projects [11] | Limited scale; often one-time donations | Research-heavy NbS, campus gardens, or pilot programs |

Green Banks/Community Lenders | Scalable financing; bridges gaps between grants and loans [7] | Requires clear return on investment metrics | Projects with measurable benefits, like reducing stormwater fees |

These varied funding mechanisms provide a strong foundation for integrating NbS into university operations and ensuring their long-term viability.

Embedding NbS into Institutional Strategy

Securing funding is just the first step - embedding NbS into the institution's long-term strategy is essential for sustained success. Instead of treating NbS as isolated projects, universities should weave them into their operational and planning frameworks. For instance, replacing conventional gray infrastructure, such as concrete pipes, with natural solutions like bioswales or restored wetlands can offer enduring environmental and economic benefits [1]. To ensure these projects remain functional over time, they must be included in routine operations and maintenance budgets [1].

Creating dedicated internal hubs to oversee NbS efforts can streamline implementation and foster collaboration across departments. Duke University exemplifies this approach, integrating NbS into both academic and operational activities [7]. Their participation in professional networks, such as the Network for Engineering With Nature, which they joined in September 2023, highlights the value of partnerships for accessing technical expertise and collaboration opportunities [7].

A successful NbS strategy should be dynamic, adapting to ongoing monitoring data and shifting climate conditions. Adaptive management protocols, which allow for modifications based on real-world results, are crucial for maintaining the effectiveness of these solutions [1]. Aligning campus goals with federal resilience frameworks and diversifying funding sources - whether through grants, philanthropy, or internal budgets - can further ensure that NbS initiatives deliver lasting impact [11].

ADB and Leiden University Seminar: Biodiversity, Climate Change and Nature-Based Solutions

Conclusion: Building Resilient and Sustainable Campuses

Universities have a unique opportunity to lead the way in creating resilient and resource-efficient campuses by weaving nature-based solutions into their core strategies. This approach goes beyond isolated projects, aiming to reimagine campuses as green, low-carbon spaces. Transitioning from traditional gray infrastructure, like concrete pipes and levees, to natural solutions such as bioswales and restored floodplains can significantly enhance sustainability efforts [1][4][6].

Collaboration plays a vital role in achieving meaningful change. For example, Duke University's partnership with the U.S. Department of the Interior resulted in a comprehensive roadmap featuring over 400 tools and 29 strategies. Such partnerships illustrate how collective efforts can extend the benefits of sustainability well beyond the campus boundaries [1][3][6].

Long-term success hinges on effective management practices. Universities must adopt adaptive management protocols that rely on monitoring data to evaluate project outcomes and refine strategies as needed [1]. For technical solutions like bioswales and rain gardens, visual indicators can help verify their performance and signal when maintenance is required [6]. Additionally, incorporating operations and maintenance plans during the design phase ensures the longevity and functionality of these natural systems [1][6].

FAQs

What funding options are available for universities to support Nature-Based Solutions projects?

Universities have several avenues to secure funding for Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) projects, tapping into federal grants, philanthropic organizations, and public-private partnerships. Federal programs such as USDA Conservation Innovation Grants, EPA Green Infrastructure funding, and DOI restoration awards often favor projects that blend ecological improvements with enhanced community resilience. These grants frequently encourage collaboration and may require matching contributions to qualify.

Building partnerships with local governments, nonprofit organizations, tribal entities, and private companies can significantly bolster funding proposals, making them more competitive for larger grants. Moreover, climate-resilience funds and philanthropic foundations often provide targeted grants for initiatives like campus greening, biodiversity efforts, and ecosystem restoration.

To increase the likelihood of securing funds, universities should ensure their project goals align with national priorities like carbon storage or flood prevention. Emphasizing co-benefits and presenting well-crafted proposals that showcase collaboration among multiple stakeholders and clear, measurable outcomes can open doors to the financial and technical resources needed to bring these NbS initiatives to fruition.

What are the best practices for implementing Nature-Based Solutions on university campuses?

To put Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) into action on campus, the first step is conducting a thorough evaluation of the university's land use, biodiversity, and climate-related challenges. From there, define clear environmental goals - whether it's enhancing stormwater management, mitigating heat islands, or increasing carbon storage - and align these objectives with the institution’s overarching sustainability plans.

Choose solutions that fit the unique needs of your campus, such as rain gardens to manage runoff, permeable pavements to reduce flooding, or green roofs to improve insulation and biodiversity. Collaboration plays a vital role in success - bring together students, faculty, facilities teams, and community partners early in the process. This approach ensures that projects are not only well-executed but also integrated into academic programs, research initiatives, and daily campus life.

To bring these solutions to life, explore innovative funding options like grants, green bonds, or partnerships. Equally important is planning for ongoing maintenance to keep projects effective and responsive to future needs. By taking these steps, universities can transform their campuses into greener, more resilient spaces while contributing to meaningful environmental and social progress.

How can universities monitor and improve their Nature-Based Solutions projects over time?

To keep Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) projects on track and effective, universities should embrace an adaptive management strategy. Begin by performing a baseline assessment of key environmental factors on campus, such as biodiversity, water quality, and soil health. This provides a clear picture of current conditions and a foundation for setting SMART goals - objectives that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. For instance, you might aim to increase native pollinator habitats by 30% over four years or cut stormwater runoff by 15% within two years.

As you move into the implementation phase, make monitoring a seamless part of everyday operations. Affordable tools like soil moisture probes can provide valuable data, while ecological surveys and service-learning programs can involve students and staff in hands-on data collection. Citizen science initiatives are another great way to engage the campus community. Regularly compare your findings to the original goals, and be ready to adapt plans as needed. This might mean redesigning green spaces, planting more native species, or tweaking maintenance routines to better support the environment.

An annual review process is key to keeping everything on track. Use this time to assess progress, share updates with stakeholders, and fine-tune your strategies for the future. This approach not only ensures projects stay aligned with ecological and institutional priorities but also builds a foundation for lasting sustainability and resilience.

Related Blog Posts

Latest Articles

©2025

FAQ

01

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

02

What makes Council Fire different?

03

Who does Council Fire you work with?

04

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

05

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

06

How does Council Fire define and measure success?

Jan 20, 2026

How to Develop a Nature-Based Solutions Strategy for Universities & Research Institutions

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Step-by-step guide for universities to plan, fund, implement, and monitor nature-based solutions—stormwater, urban greening, biodiversity, and campus resilience.

How to Develop a Nature-Based Solutions Strategy for Universities & Research Institutions

Universities can lead the way in addressing environmental challenges by integrating Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) into their campuses. These approaches use natural systems like rain gardens, bioswales, and urban forests to manage issues such as stormwater, heat, and biodiversity loss. Beyond ecological benefits, NbS can improve campus operations, create learning opportunities, and align with sustainability goals.

Key steps to develop an NbS strategy:

Understand NbS Basics: Focus on using natural systems to solve environmental and societal challenges.

Assess Campus Needs: Conduct biodiversity and infrastructure evaluations to identify gaps and opportunities.

Engage Stakeholders: Involve faculty, students, and external partners in planning and implementation.

Plan and Prioritize Projects: Select initiatives based on site suitability, resources, and long-term maintenance.

Secure Funding: Leverage federal grants, partnerships, and philanthropic contributions to support projects.

Monitor and Adjust: Use tools and metrics to track progress and refine strategies over time.

6-Step Process for Developing Nature-Based Solutions Strategy at Universities

Understanding Nature-Based Solutions Basics

What Are Nature-Based Solutions?

Nature-based solutions (NbS) focus on protecting, managing, and restoring natural and managed ecosystems to tackle societal challenges while benefiting both people and the environment [1][8]. Unlike traditional gray infrastructure, NbS use natural systems such as rain gardens or urban forests to address environmental needs effectively.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) succinctly explains:

"Nature-based solutions leverage nature and the power of healthy ecosystems to protect people, optimise infrastructure and safeguard a stable and biodiverse future." [8]

These approaches offer more than just functionality - they provide multiple benefits. For example, a bioswale on campus not only manages stormwater runoff but also supports wildlife habitats, reduces flood risks, and creates green spaces for students to enjoy. On a global scale, NbS are powerful tools. They could deliver about one-third of the climate mitigation required to meet the Paris Agreement goals, with ecosystem services valued at $170 billion annually [8]. Specific measures, like mangroves, prevent approximately $57 billion in flood damages each year, including in the United States [8].

This foundational understanding highlights the importance of applying guiding principles to integrate NbS effectively into campus planning.

Core Principles of NbS for Universities

For universities to successfully implement NbS, they need to follow key principles. Solutions should aim for net positive biodiversity outcomes and be designed to address future climate conditions. For instance, selecting tree species that can thrive in warmer climates or placing wetlands strategically to handle stronger storms ensures long-term success.

Equity and community involvement are equally vital. Katie Warnell from the Nicholas Institute emphasizes that while many institutions already use NbS strategies, they often miss opportunities to maximize their impact:

"While [institutions] already use many of the strategies included in the Roadmap, these projects are not always designed using a nature-based solutions framing. The approaches and information in the Roadmap can help expand value to both people and nature." [7]

This underscores the importance of engaging students, faculty, staff, and nearby communities in planning efforts. Incorporating Indigenous Knowledges when appropriate and ensuring projects serve all groups equitably are also essential steps [1][7]. Additionally, universities should treat natural systems as infrastructure, not just as decorative landscaping. For example, a healthy riparian buffer along a campus stream offers critical services like erosion control and water filtration. By embedding these principles into campus planning, NbS can function as essential infrastructure.

Finally, adaptive management is crucial. Regular monitoring allows universities to assess project performance and make necessary adjustments based on collected data and evolving conditions [1].

NbS Strategy | Campus Application | Primary Environmental Benefit |

|---|---|---|

Bioretention | Rain gardens, bioswales | Manages stormwater and runoff |

Urban Greening | Campus forests, tree planting | Reduces heat and supports human health |

Riparian Restoration | Stream buffer zones | Improves water quality and prevents erosion |

Permeable Pavement | Parking lots, walkways | Minimizes flooding and runoff |

Ecosystem Restoration | Wetland or meadow restoration | Enhances biodiversity and captures carbon |

Assessing Your Institution's Needs and Resources

Conduct Environmental and Biodiversity Assessments

Before launching Nature-based Solutions (NbS) projects, it’s essential to evaluate your campus's current environmental conditions and resilience. According to Second Nature, resilience is shaped by unique local factors, including specific goals, capacities, and vulnerabilities [9]. Start with a comprehensive environmental and biodiversity assessment that examines five key areas: Ecosystem Services, Infrastructure (both traditional and green systems), Social Equity & Governance, Health & Wellness, and Economic considerations [9].

Take a close look at how existing wetlands, forests, and green spaces perform. Do these areas effectively manage stormwater runoff, provide cooling during heat waves, or support local biodiversity? These insights can help identify where natural systems could replace or complement traditional engineered solutions [1]. Incorporate adaptive management strategies that continuously monitor these natural systems, and involve diverse stakeholders - faculty, students, facilities staff, and community members. As Second Nature highlights:

"the most successful plans embrace the catalytic nature of social engagement" [9]

This process will help uncover campus-specific challenges and opportunities for enhancing resilience.

Identify Campus-Specific Challenges and Opportunities

Once you’ve established a baseline assessment, focus on identifying the unique challenges and opportunities your campus faces. Tools like asset mapping can go beyond physical infrastructure to include faculty expertise, student participation, financial resources, and partnerships with the surrounding community [10].

Use methods such as SWOT analysis and visioning exercises to explore potential scenarios for the coming decades. These activities can help balance broader priorities - like advancing research or increasing student diversity - with climate-related goals [10]. Sometimes, these sessions reveal unexpected opportunities. For instance, unused parking lots could be transformed into bioswales, or neglected stream corridors might be restored to serve as outdoor classrooms. Seek out projects that offer multiple benefits, such as green roofs that reduce stormwater runoff, lower cooling costs, and create habitats for wildlife [1].

To ensure these efforts are sustainable and not just one-off initiatives, integrate NbS objectives into your institution’s long-term plans. Align them with 5-year budgets and 10-year master plans, embedding these strategies into the broader framework [10]. Focus on high-impact, low-cost projects, such as LED lighting upgrades, which can save over $1,000,000 annually while reducing energy use by 25% [10]. By doing so, you can make NbS a lasting part of your institution's development.

Engaging Stakeholders for Collaborative NbS Development

Internal Stakeholder Collaboration

Developing an effective Nature-based Solutions (NbS) strategy depends on the active involvement of internal stakeholders such as faculty, students, and administrative staff. Faculty often take on roles as technical experts and project leaders, guiding the scientific and practical aspects of initiatives. Meanwhile, students can contribute as researchers and even co-authors on institutional plans, gaining valuable hands-on experience. Administrative staff, on the other hand, ensure the smooth execution of day-to-day operations, bridging the gap between planning and implementation.

Take the example of Duke University, where a faculty-led team crafted the DOI Nature-Based Solutions Roadmap in December 2023. This roadmap outlined 29 different NbS strategies and included over 400 case studies. As Katie Warnell explained:

"The approaches and information in the Roadmap can help expand value to both people and nature." [7]

To deepen engagement, institutions can integrate green infrastructure projects into their academic curriculum, offering students opportunities to gain professional skills while contributing to sustainability goals. Establishing specialized research hubs, such as a Wetland Center or campus-focused restoration programs, can further centralize efforts and encourage collaboration on specific themes. These initiatives not only enhance learning but also create a cohesive internal framework that can be expanded through external collaborations.

Building Partnerships with External Organizations

While internal collaboration lays the groundwork, partnerships with external organizations significantly broaden the impact and reach of NbS strategies. Collaborating with federal, state, and local governments, nonprofits, tribal groups, community organizations, and private sector entities brings together diverse expertise in fields like ecology, engineering, and urban planning. This multidisciplinary approach is essential for tackling complex environmental challenges.

For instance, in September 2023, Duke University joined the Network for Engineering With Nature, a group of researchers and practitioners focused on using natural features to address U.S. infrastructure challenges. Spearheaded by the Nicholas Institute and the Pratt School of Engineering, this partnership has allowed Duke to work closely with federal agencies and other academic institutions.[7]

These external collaborations provide access to technical expertise, regulatory insights, and critical funding opportunities, significantly amplifying the benefits of NbS. Programs like FEMA's Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities initiative or the EPA's Urban Waters Small Grants offer financial support to advance such partnerships. These resources help deliver tangible outcomes, such as improved water quality and greater climate resilience, while fostering long-term, impactful solutions.

Designing and Implementing NbS Action Plans

Selecting and Prioritizing NbS Projects

After conducting campus assessments and identifying opportunities, the next step is selecting projects that align with your institution's sustainability goals. Focus on initiatives that provide clear benefits for both people and the environment. Evaluate each project based on its suitability for the site, the resources required for implementation, and the long-term maintenance it will need.

Duke University's 2023 Nature-Based Solutions Roadmap serves as a valuable guide for this process. It outlines 29 nature-based strategies and includes over 400 case studies, offering practical insights into project selection and execution. Developed by experts like Lydia Olander and Katie Warnell, the roadmap emphasizes transitioning from traditional, gray infrastructure to natural alternatives, with detailed guidance on site-specific considerations and ongoing upkeep requirements.[1][7]

When narrowing down projects, apply overarching principles such as engaging the community and incorporating Indigenous Knowledges to ensure initiatives are relevant and inclusive. Tools like the EPA's Climate Resilience Evaluation & Awareness Tool (CREAT) can help identify climate risks to campus assets, while the Climate Smart Restoration Tool aids in selecting native plants suited to future climate conditions at your location.[6]

This thoughtful selection process lays the groundwork for weaving nature-based solutions (NbS) into the fabric of campus life.

Integrating NbS into Campus Operations

To fully embrace NbS, connect these projects to both infrastructure upgrades and educational opportunities. Universities can extend the impact of "green campus" initiatives by embedding them into a "green curriculum", creating a ripple effect that reaches beyond landscaping into the institution’s academic mission.[5] This could involve incorporating green infrastructure projects into coursework, establishing research hubs like wetland labs, or updating landscaping policies to prioritize native species and ecosystem health.

Duke University provides a strong example of this integration. In September 2023, the university joined the Network for Engineering With Nature (N-EWN), a collaboration led by the Nicholas Institute and involving the Nicholas School of the Environment and the Pratt School of Engineering. This initiative brings nature-based engineering into both research and campus operations, showcasing how sustainability can be made a visible and actionable part of university life.[7] By transitioning from traditional infrastructure to natural or hybrid systems, institutions can make sustainability a core component of daily operations.

With NbS projects in place, ongoing monitoring ensures their continued success and relevance.

Using Monitoring Tools and Metrics

Once projects are implemented, consistent monitoring is critical to validate their impact and guide adjustments. Choose monitoring tools that align with your institution’s resources and the specific nature of each project. The Urban Nature Indexes (UNI) framework offers a comprehensive approach, covering 30 indicator topics across six themes: consumption drivers, human pressures, habitat status, species status, nature’s benefits to people, and governance responses.[12] For campuses with limited resources, begin with straightforward metrics like air and water quality or waste reduction, and expand to more complex indicators over time.

Visual inspection tools, such as Bioretention Illustrated, can help assess the performance of green infrastructure. Schedule periodic evaluations - every one to five years - to track ecological trends and determine whether conditions are improving, remaining steady, or declining. The DOI Nature-Based Solutions Roadmap provides links to specific monitoring tools and training resources for each of the 29 NbS strategies, offering practical support for tracking progress.[1][7]

As Lydia Olander, Program Director at Duke's Nicholas Institute, observed:

"Support for nature-based solutions is growing rapidly across the United States as a way to improve the resilience of our communities and ecosystems."[7]

This increasing momentum underscores the importance of robust monitoring to demonstrate the value of NbS and maintain institutional commitment.

Securing Funding and Ensuring Long-Term Success

Funding Mechanisms for NbS

Universities aiming to implement Nature-based Solutions (NbS) can tap into a variety of funding sources, including federal grants, public-private partnerships, green banks, and philanthropic contributions. Among these, federal grants are often the most substantial. Agencies like FEMA, the EPA, USDA, and the Department of the Interior (DOI) provide targeted support for large-scale projects. By early 2025, FEMA had already issued 119 hazard mitigation assistance sub-grants, totaling $874 million for disaster relief and mitigation efforts [2]. The DOI, which oversees more than 480 million acres of federal lands, is a key collaborator for expansive NbS initiatives [7].

Public-private partnerships offer an opportunity to pool resources while sharing risks and expertise among government, nonprofit, and private entities. These partnerships can bring innovative solutions but often require careful alignment of interests. On the other hand, green banks and community lenders provide long-term capital for projects that fall outside traditional grant cycles [7]. For smaller, research-focused efforts, philanthropic contributions offer flexibility, especially for pilot programs and initiatives that may not meet standard funding criteria [11].

To improve the chances of securing funding, universities should form cross-disciplinary teams, bringing together ecologists, engineers, planners, and other experts. These teams can craft compelling grant proposals that appeal to multiple funding sources [11].

Funding Source | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

Federal Grants (FEMA, EPA, USDA) | High funding potential; supports large-scale infrastructure [11] | Competitive process; strict reporting requirements [11] | Large projects like flood prevention or watershed restoration |

Public-Private Partnerships | Shared financial risk; access to private sector expertise [11] | Complex legal arrangements; requires aligned goals | Urban infrastructure or community-university collaborations |

Philanthropic Contributions | Flexible funding; ideal for pilot projects [11] | Limited scale; often one-time donations | Research-heavy NbS, campus gardens, or pilot programs |

Green Banks/Community Lenders | Scalable financing; bridges gaps between grants and loans [7] | Requires clear return on investment metrics | Projects with measurable benefits, like reducing stormwater fees |

These varied funding mechanisms provide a strong foundation for integrating NbS into university operations and ensuring their long-term viability.

Embedding NbS into Institutional Strategy

Securing funding is just the first step - embedding NbS into the institution's long-term strategy is essential for sustained success. Instead of treating NbS as isolated projects, universities should weave them into their operational and planning frameworks. For instance, replacing conventional gray infrastructure, such as concrete pipes, with natural solutions like bioswales or restored wetlands can offer enduring environmental and economic benefits [1]. To ensure these projects remain functional over time, they must be included in routine operations and maintenance budgets [1].

Creating dedicated internal hubs to oversee NbS efforts can streamline implementation and foster collaboration across departments. Duke University exemplifies this approach, integrating NbS into both academic and operational activities [7]. Their participation in professional networks, such as the Network for Engineering With Nature, which they joined in September 2023, highlights the value of partnerships for accessing technical expertise and collaboration opportunities [7].

A successful NbS strategy should be dynamic, adapting to ongoing monitoring data and shifting climate conditions. Adaptive management protocols, which allow for modifications based on real-world results, are crucial for maintaining the effectiveness of these solutions [1]. Aligning campus goals with federal resilience frameworks and diversifying funding sources - whether through grants, philanthropy, or internal budgets - can further ensure that NbS initiatives deliver lasting impact [11].

ADB and Leiden University Seminar: Biodiversity, Climate Change and Nature-Based Solutions

Conclusion: Building Resilient and Sustainable Campuses

Universities have a unique opportunity to lead the way in creating resilient and resource-efficient campuses by weaving nature-based solutions into their core strategies. This approach goes beyond isolated projects, aiming to reimagine campuses as green, low-carbon spaces. Transitioning from traditional gray infrastructure, like concrete pipes and levees, to natural solutions such as bioswales and restored floodplains can significantly enhance sustainability efforts [1][4][6].

Collaboration plays a vital role in achieving meaningful change. For example, Duke University's partnership with the U.S. Department of the Interior resulted in a comprehensive roadmap featuring over 400 tools and 29 strategies. Such partnerships illustrate how collective efforts can extend the benefits of sustainability well beyond the campus boundaries [1][3][6].

Long-term success hinges on effective management practices. Universities must adopt adaptive management protocols that rely on monitoring data to evaluate project outcomes and refine strategies as needed [1]. For technical solutions like bioswales and rain gardens, visual indicators can help verify their performance and signal when maintenance is required [6]. Additionally, incorporating operations and maintenance plans during the design phase ensures the longevity and functionality of these natural systems [1][6].

FAQs

What funding options are available for universities to support Nature-Based Solutions projects?

Universities have several avenues to secure funding for Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) projects, tapping into federal grants, philanthropic organizations, and public-private partnerships. Federal programs such as USDA Conservation Innovation Grants, EPA Green Infrastructure funding, and DOI restoration awards often favor projects that blend ecological improvements with enhanced community resilience. These grants frequently encourage collaboration and may require matching contributions to qualify.

Building partnerships with local governments, nonprofit organizations, tribal entities, and private companies can significantly bolster funding proposals, making them more competitive for larger grants. Moreover, climate-resilience funds and philanthropic foundations often provide targeted grants for initiatives like campus greening, biodiversity efforts, and ecosystem restoration.

To increase the likelihood of securing funds, universities should ensure their project goals align with national priorities like carbon storage or flood prevention. Emphasizing co-benefits and presenting well-crafted proposals that showcase collaboration among multiple stakeholders and clear, measurable outcomes can open doors to the financial and technical resources needed to bring these NbS initiatives to fruition.

What are the best practices for implementing Nature-Based Solutions on university campuses?

To put Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) into action on campus, the first step is conducting a thorough evaluation of the university's land use, biodiversity, and climate-related challenges. From there, define clear environmental goals - whether it's enhancing stormwater management, mitigating heat islands, or increasing carbon storage - and align these objectives with the institution’s overarching sustainability plans.

Choose solutions that fit the unique needs of your campus, such as rain gardens to manage runoff, permeable pavements to reduce flooding, or green roofs to improve insulation and biodiversity. Collaboration plays a vital role in success - bring together students, faculty, facilities teams, and community partners early in the process. This approach ensures that projects are not only well-executed but also integrated into academic programs, research initiatives, and daily campus life.

To bring these solutions to life, explore innovative funding options like grants, green bonds, or partnerships. Equally important is planning for ongoing maintenance to keep projects effective and responsive to future needs. By taking these steps, universities can transform their campuses into greener, more resilient spaces while contributing to meaningful environmental and social progress.

How can universities monitor and improve their Nature-Based Solutions projects over time?

To keep Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) projects on track and effective, universities should embrace an adaptive management strategy. Begin by performing a baseline assessment of key environmental factors on campus, such as biodiversity, water quality, and soil health. This provides a clear picture of current conditions and a foundation for setting SMART goals - objectives that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. For instance, you might aim to increase native pollinator habitats by 30% over four years or cut stormwater runoff by 15% within two years.

As you move into the implementation phase, make monitoring a seamless part of everyday operations. Affordable tools like soil moisture probes can provide valuable data, while ecological surveys and service-learning programs can involve students and staff in hands-on data collection. Citizen science initiatives are another great way to engage the campus community. Regularly compare your findings to the original goals, and be ready to adapt plans as needed. This might mean redesigning green spaces, planting more native species, or tweaking maintenance routines to better support the environment.

An annual review process is key to keeping everything on track. Use this time to assess progress, share updates with stakeholders, and fine-tune your strategies for the future. This approach not only ensures projects stay aligned with ecological and institutional priorities but also builds a foundation for lasting sustainability and resilience.

Related Blog Posts

FAQ

01

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

02

What makes Council Fire different?

03

Who does Council Fire you work with?

04

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

05

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

06

How does Council Fire define and measure success?

Jan 20, 2026

How to Develop a Nature-Based Solutions Strategy for Universities & Research Institutions

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Step-by-step guide for universities to plan, fund, implement, and monitor nature-based solutions—stormwater, urban greening, biodiversity, and campus resilience.

How to Develop a Nature-Based Solutions Strategy for Universities & Research Institutions

Universities can lead the way in addressing environmental challenges by integrating Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) into their campuses. These approaches use natural systems like rain gardens, bioswales, and urban forests to manage issues such as stormwater, heat, and biodiversity loss. Beyond ecological benefits, NbS can improve campus operations, create learning opportunities, and align with sustainability goals.

Key steps to develop an NbS strategy:

Understand NbS Basics: Focus on using natural systems to solve environmental and societal challenges.

Assess Campus Needs: Conduct biodiversity and infrastructure evaluations to identify gaps and opportunities.

Engage Stakeholders: Involve faculty, students, and external partners in planning and implementation.

Plan and Prioritize Projects: Select initiatives based on site suitability, resources, and long-term maintenance.

Secure Funding: Leverage federal grants, partnerships, and philanthropic contributions to support projects.

Monitor and Adjust: Use tools and metrics to track progress and refine strategies over time.

6-Step Process for Developing Nature-Based Solutions Strategy at Universities

Understanding Nature-Based Solutions Basics

What Are Nature-Based Solutions?

Nature-based solutions (NbS) focus on protecting, managing, and restoring natural and managed ecosystems to tackle societal challenges while benefiting both people and the environment [1][8]. Unlike traditional gray infrastructure, NbS use natural systems such as rain gardens or urban forests to address environmental needs effectively.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) succinctly explains:

"Nature-based solutions leverage nature and the power of healthy ecosystems to protect people, optimise infrastructure and safeguard a stable and biodiverse future." [8]

These approaches offer more than just functionality - they provide multiple benefits. For example, a bioswale on campus not only manages stormwater runoff but also supports wildlife habitats, reduces flood risks, and creates green spaces for students to enjoy. On a global scale, NbS are powerful tools. They could deliver about one-third of the climate mitigation required to meet the Paris Agreement goals, with ecosystem services valued at $170 billion annually [8]. Specific measures, like mangroves, prevent approximately $57 billion in flood damages each year, including in the United States [8].

This foundational understanding highlights the importance of applying guiding principles to integrate NbS effectively into campus planning.

Core Principles of NbS for Universities

For universities to successfully implement NbS, they need to follow key principles. Solutions should aim for net positive biodiversity outcomes and be designed to address future climate conditions. For instance, selecting tree species that can thrive in warmer climates or placing wetlands strategically to handle stronger storms ensures long-term success.

Equity and community involvement are equally vital. Katie Warnell from the Nicholas Institute emphasizes that while many institutions already use NbS strategies, they often miss opportunities to maximize their impact:

"While [institutions] already use many of the strategies included in the Roadmap, these projects are not always designed using a nature-based solutions framing. The approaches and information in the Roadmap can help expand value to both people and nature." [7]

This underscores the importance of engaging students, faculty, staff, and nearby communities in planning efforts. Incorporating Indigenous Knowledges when appropriate and ensuring projects serve all groups equitably are also essential steps [1][7]. Additionally, universities should treat natural systems as infrastructure, not just as decorative landscaping. For example, a healthy riparian buffer along a campus stream offers critical services like erosion control and water filtration. By embedding these principles into campus planning, NbS can function as essential infrastructure.

Finally, adaptive management is crucial. Regular monitoring allows universities to assess project performance and make necessary adjustments based on collected data and evolving conditions [1].

NbS Strategy | Campus Application | Primary Environmental Benefit |

|---|---|---|

Bioretention | Rain gardens, bioswales | Manages stormwater and runoff |

Urban Greening | Campus forests, tree planting | Reduces heat and supports human health |

Riparian Restoration | Stream buffer zones | Improves water quality and prevents erosion |

Permeable Pavement | Parking lots, walkways | Minimizes flooding and runoff |

Ecosystem Restoration | Wetland or meadow restoration | Enhances biodiversity and captures carbon |

Assessing Your Institution's Needs and Resources

Conduct Environmental and Biodiversity Assessments

Before launching Nature-based Solutions (NbS) projects, it’s essential to evaluate your campus's current environmental conditions and resilience. According to Second Nature, resilience is shaped by unique local factors, including specific goals, capacities, and vulnerabilities [9]. Start with a comprehensive environmental and biodiversity assessment that examines five key areas: Ecosystem Services, Infrastructure (both traditional and green systems), Social Equity & Governance, Health & Wellness, and Economic considerations [9].

Take a close look at how existing wetlands, forests, and green spaces perform. Do these areas effectively manage stormwater runoff, provide cooling during heat waves, or support local biodiversity? These insights can help identify where natural systems could replace or complement traditional engineered solutions [1]. Incorporate adaptive management strategies that continuously monitor these natural systems, and involve diverse stakeholders - faculty, students, facilities staff, and community members. As Second Nature highlights:

"the most successful plans embrace the catalytic nature of social engagement" [9]

This process will help uncover campus-specific challenges and opportunities for enhancing resilience.

Identify Campus-Specific Challenges and Opportunities

Once you’ve established a baseline assessment, focus on identifying the unique challenges and opportunities your campus faces. Tools like asset mapping can go beyond physical infrastructure to include faculty expertise, student participation, financial resources, and partnerships with the surrounding community [10].

Use methods such as SWOT analysis and visioning exercises to explore potential scenarios for the coming decades. These activities can help balance broader priorities - like advancing research or increasing student diversity - with climate-related goals [10]. Sometimes, these sessions reveal unexpected opportunities. For instance, unused parking lots could be transformed into bioswales, or neglected stream corridors might be restored to serve as outdoor classrooms. Seek out projects that offer multiple benefits, such as green roofs that reduce stormwater runoff, lower cooling costs, and create habitats for wildlife [1].

To ensure these efforts are sustainable and not just one-off initiatives, integrate NbS objectives into your institution’s long-term plans. Align them with 5-year budgets and 10-year master plans, embedding these strategies into the broader framework [10]. Focus on high-impact, low-cost projects, such as LED lighting upgrades, which can save over $1,000,000 annually while reducing energy use by 25% [10]. By doing so, you can make NbS a lasting part of your institution's development.

Engaging Stakeholders for Collaborative NbS Development

Internal Stakeholder Collaboration

Developing an effective Nature-based Solutions (NbS) strategy depends on the active involvement of internal stakeholders such as faculty, students, and administrative staff. Faculty often take on roles as technical experts and project leaders, guiding the scientific and practical aspects of initiatives. Meanwhile, students can contribute as researchers and even co-authors on institutional plans, gaining valuable hands-on experience. Administrative staff, on the other hand, ensure the smooth execution of day-to-day operations, bridging the gap between planning and implementation.

Take the example of Duke University, where a faculty-led team crafted the DOI Nature-Based Solutions Roadmap in December 2023. This roadmap outlined 29 different NbS strategies and included over 400 case studies. As Katie Warnell explained:

"The approaches and information in the Roadmap can help expand value to both people and nature." [7]

To deepen engagement, institutions can integrate green infrastructure projects into their academic curriculum, offering students opportunities to gain professional skills while contributing to sustainability goals. Establishing specialized research hubs, such as a Wetland Center or campus-focused restoration programs, can further centralize efforts and encourage collaboration on specific themes. These initiatives not only enhance learning but also create a cohesive internal framework that can be expanded through external collaborations.

Building Partnerships with External Organizations

While internal collaboration lays the groundwork, partnerships with external organizations significantly broaden the impact and reach of NbS strategies. Collaborating with federal, state, and local governments, nonprofits, tribal groups, community organizations, and private sector entities brings together diverse expertise in fields like ecology, engineering, and urban planning. This multidisciplinary approach is essential for tackling complex environmental challenges.

For instance, in September 2023, Duke University joined the Network for Engineering With Nature, a group of researchers and practitioners focused on using natural features to address U.S. infrastructure challenges. Spearheaded by the Nicholas Institute and the Pratt School of Engineering, this partnership has allowed Duke to work closely with federal agencies and other academic institutions.[7]

These external collaborations provide access to technical expertise, regulatory insights, and critical funding opportunities, significantly amplifying the benefits of NbS. Programs like FEMA's Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities initiative or the EPA's Urban Waters Small Grants offer financial support to advance such partnerships. These resources help deliver tangible outcomes, such as improved water quality and greater climate resilience, while fostering long-term, impactful solutions.

Designing and Implementing NbS Action Plans

Selecting and Prioritizing NbS Projects

After conducting campus assessments and identifying opportunities, the next step is selecting projects that align with your institution's sustainability goals. Focus on initiatives that provide clear benefits for both people and the environment. Evaluate each project based on its suitability for the site, the resources required for implementation, and the long-term maintenance it will need.

Duke University's 2023 Nature-Based Solutions Roadmap serves as a valuable guide for this process. It outlines 29 nature-based strategies and includes over 400 case studies, offering practical insights into project selection and execution. Developed by experts like Lydia Olander and Katie Warnell, the roadmap emphasizes transitioning from traditional, gray infrastructure to natural alternatives, with detailed guidance on site-specific considerations and ongoing upkeep requirements.[1][7]

When narrowing down projects, apply overarching principles such as engaging the community and incorporating Indigenous Knowledges to ensure initiatives are relevant and inclusive. Tools like the EPA's Climate Resilience Evaluation & Awareness Tool (CREAT) can help identify climate risks to campus assets, while the Climate Smart Restoration Tool aids in selecting native plants suited to future climate conditions at your location.[6]

This thoughtful selection process lays the groundwork for weaving nature-based solutions (NbS) into the fabric of campus life.

Integrating NbS into Campus Operations

To fully embrace NbS, connect these projects to both infrastructure upgrades and educational opportunities. Universities can extend the impact of "green campus" initiatives by embedding them into a "green curriculum", creating a ripple effect that reaches beyond landscaping into the institution’s academic mission.[5] This could involve incorporating green infrastructure projects into coursework, establishing research hubs like wetland labs, or updating landscaping policies to prioritize native species and ecosystem health.

Duke University provides a strong example of this integration. In September 2023, the university joined the Network for Engineering With Nature (N-EWN), a collaboration led by the Nicholas Institute and involving the Nicholas School of the Environment and the Pratt School of Engineering. This initiative brings nature-based engineering into both research and campus operations, showcasing how sustainability can be made a visible and actionable part of university life.[7] By transitioning from traditional infrastructure to natural or hybrid systems, institutions can make sustainability a core component of daily operations.

With NbS projects in place, ongoing monitoring ensures their continued success and relevance.

Using Monitoring Tools and Metrics

Once projects are implemented, consistent monitoring is critical to validate their impact and guide adjustments. Choose monitoring tools that align with your institution’s resources and the specific nature of each project. The Urban Nature Indexes (UNI) framework offers a comprehensive approach, covering 30 indicator topics across six themes: consumption drivers, human pressures, habitat status, species status, nature’s benefits to people, and governance responses.[12] For campuses with limited resources, begin with straightforward metrics like air and water quality or waste reduction, and expand to more complex indicators over time.

Visual inspection tools, such as Bioretention Illustrated, can help assess the performance of green infrastructure. Schedule periodic evaluations - every one to five years - to track ecological trends and determine whether conditions are improving, remaining steady, or declining. The DOI Nature-Based Solutions Roadmap provides links to specific monitoring tools and training resources for each of the 29 NbS strategies, offering practical support for tracking progress.[1][7]

As Lydia Olander, Program Director at Duke's Nicholas Institute, observed:

"Support for nature-based solutions is growing rapidly across the United States as a way to improve the resilience of our communities and ecosystems."[7]

This increasing momentum underscores the importance of robust monitoring to demonstrate the value of NbS and maintain institutional commitment.

Securing Funding and Ensuring Long-Term Success

Funding Mechanisms for NbS

Universities aiming to implement Nature-based Solutions (NbS) can tap into a variety of funding sources, including federal grants, public-private partnerships, green banks, and philanthropic contributions. Among these, federal grants are often the most substantial. Agencies like FEMA, the EPA, USDA, and the Department of the Interior (DOI) provide targeted support for large-scale projects. By early 2025, FEMA had already issued 119 hazard mitigation assistance sub-grants, totaling $874 million for disaster relief and mitigation efforts [2]. The DOI, which oversees more than 480 million acres of federal lands, is a key collaborator for expansive NbS initiatives [7].

Public-private partnerships offer an opportunity to pool resources while sharing risks and expertise among government, nonprofit, and private entities. These partnerships can bring innovative solutions but often require careful alignment of interests. On the other hand, green banks and community lenders provide long-term capital for projects that fall outside traditional grant cycles [7]. For smaller, research-focused efforts, philanthropic contributions offer flexibility, especially for pilot programs and initiatives that may not meet standard funding criteria [11].

To improve the chances of securing funding, universities should form cross-disciplinary teams, bringing together ecologists, engineers, planners, and other experts. These teams can craft compelling grant proposals that appeal to multiple funding sources [11].

Funding Source | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

Federal Grants (FEMA, EPA, USDA) | High funding potential; supports large-scale infrastructure [11] | Competitive process; strict reporting requirements [11] | Large projects like flood prevention or watershed restoration |

Public-Private Partnerships | Shared financial risk; access to private sector expertise [11] | Complex legal arrangements; requires aligned goals | Urban infrastructure or community-university collaborations |

Philanthropic Contributions | Flexible funding; ideal for pilot projects [11] | Limited scale; often one-time donations | Research-heavy NbS, campus gardens, or pilot programs |

Green Banks/Community Lenders | Scalable financing; bridges gaps between grants and loans [7] | Requires clear return on investment metrics | Projects with measurable benefits, like reducing stormwater fees |

These varied funding mechanisms provide a strong foundation for integrating NbS into university operations and ensuring their long-term viability.

Embedding NbS into Institutional Strategy

Securing funding is just the first step - embedding NbS into the institution's long-term strategy is essential for sustained success. Instead of treating NbS as isolated projects, universities should weave them into their operational and planning frameworks. For instance, replacing conventional gray infrastructure, such as concrete pipes, with natural solutions like bioswales or restored wetlands can offer enduring environmental and economic benefits [1]. To ensure these projects remain functional over time, they must be included in routine operations and maintenance budgets [1].

Creating dedicated internal hubs to oversee NbS efforts can streamline implementation and foster collaboration across departments. Duke University exemplifies this approach, integrating NbS into both academic and operational activities [7]. Their participation in professional networks, such as the Network for Engineering With Nature, which they joined in September 2023, highlights the value of partnerships for accessing technical expertise and collaboration opportunities [7].

A successful NbS strategy should be dynamic, adapting to ongoing monitoring data and shifting climate conditions. Adaptive management protocols, which allow for modifications based on real-world results, are crucial for maintaining the effectiveness of these solutions [1]. Aligning campus goals with federal resilience frameworks and diversifying funding sources - whether through grants, philanthropy, or internal budgets - can further ensure that NbS initiatives deliver lasting impact [11].

ADB and Leiden University Seminar: Biodiversity, Climate Change and Nature-Based Solutions

Conclusion: Building Resilient and Sustainable Campuses

Universities have a unique opportunity to lead the way in creating resilient and resource-efficient campuses by weaving nature-based solutions into their core strategies. This approach goes beyond isolated projects, aiming to reimagine campuses as green, low-carbon spaces. Transitioning from traditional gray infrastructure, like concrete pipes and levees, to natural solutions such as bioswales and restored floodplains can significantly enhance sustainability efforts [1][4][6].

Collaboration plays a vital role in achieving meaningful change. For example, Duke University's partnership with the U.S. Department of the Interior resulted in a comprehensive roadmap featuring over 400 tools and 29 strategies. Such partnerships illustrate how collective efforts can extend the benefits of sustainability well beyond the campus boundaries [1][3][6].

Long-term success hinges on effective management practices. Universities must adopt adaptive management protocols that rely on monitoring data to evaluate project outcomes and refine strategies as needed [1]. For technical solutions like bioswales and rain gardens, visual indicators can help verify their performance and signal when maintenance is required [6]. Additionally, incorporating operations and maintenance plans during the design phase ensures the longevity and functionality of these natural systems [1][6].

FAQs

What funding options are available for universities to support Nature-Based Solutions projects?

Universities have several avenues to secure funding for Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) projects, tapping into federal grants, philanthropic organizations, and public-private partnerships. Federal programs such as USDA Conservation Innovation Grants, EPA Green Infrastructure funding, and DOI restoration awards often favor projects that blend ecological improvements with enhanced community resilience. These grants frequently encourage collaboration and may require matching contributions to qualify.

Building partnerships with local governments, nonprofit organizations, tribal entities, and private companies can significantly bolster funding proposals, making them more competitive for larger grants. Moreover, climate-resilience funds and philanthropic foundations often provide targeted grants for initiatives like campus greening, biodiversity efforts, and ecosystem restoration.

To increase the likelihood of securing funds, universities should ensure their project goals align with national priorities like carbon storage or flood prevention. Emphasizing co-benefits and presenting well-crafted proposals that showcase collaboration among multiple stakeholders and clear, measurable outcomes can open doors to the financial and technical resources needed to bring these NbS initiatives to fruition.

What are the best practices for implementing Nature-Based Solutions on university campuses?

To put Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) into action on campus, the first step is conducting a thorough evaluation of the university's land use, biodiversity, and climate-related challenges. From there, define clear environmental goals - whether it's enhancing stormwater management, mitigating heat islands, or increasing carbon storage - and align these objectives with the institution’s overarching sustainability plans.

Choose solutions that fit the unique needs of your campus, such as rain gardens to manage runoff, permeable pavements to reduce flooding, or green roofs to improve insulation and biodiversity. Collaboration plays a vital role in success - bring together students, faculty, facilities teams, and community partners early in the process. This approach ensures that projects are not only well-executed but also integrated into academic programs, research initiatives, and daily campus life.

To bring these solutions to life, explore innovative funding options like grants, green bonds, or partnerships. Equally important is planning for ongoing maintenance to keep projects effective and responsive to future needs. By taking these steps, universities can transform their campuses into greener, more resilient spaces while contributing to meaningful environmental and social progress.

How can universities monitor and improve their Nature-Based Solutions projects over time?

To keep Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) projects on track and effective, universities should embrace an adaptive management strategy. Begin by performing a baseline assessment of key environmental factors on campus, such as biodiversity, water quality, and soil health. This provides a clear picture of current conditions and a foundation for setting SMART goals - objectives that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. For instance, you might aim to increase native pollinator habitats by 30% over four years or cut stormwater runoff by 15% within two years.

As you move into the implementation phase, make monitoring a seamless part of everyday operations. Affordable tools like soil moisture probes can provide valuable data, while ecological surveys and service-learning programs can involve students and staff in hands-on data collection. Citizen science initiatives are another great way to engage the campus community. Regularly compare your findings to the original goals, and be ready to adapt plans as needed. This might mean redesigning green spaces, planting more native species, or tweaking maintenance routines to better support the environment.

An annual review process is key to keeping everything on track. Use this time to assess progress, share updates with stakeholders, and fine-tune your strategies for the future. This approach not only ensures projects stay aligned with ecological and institutional priorities but also builds a foundation for lasting sustainability and resilience.

Related Blog Posts

FAQ

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

What makes Council Fire different?

Who does Council Fire you work with?

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

How does Council Fire define and measure success?