Feb 1, 2026

Feb 1, 2026

How to Build Heat Resilience & Urban Greening for Universities & Research Institutions

Sustainability Strategy

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Actionable guidance for universities to map heat risks, expand urban greening, set up cooling centers, protect vulnerable groups, and monitor outcomes.

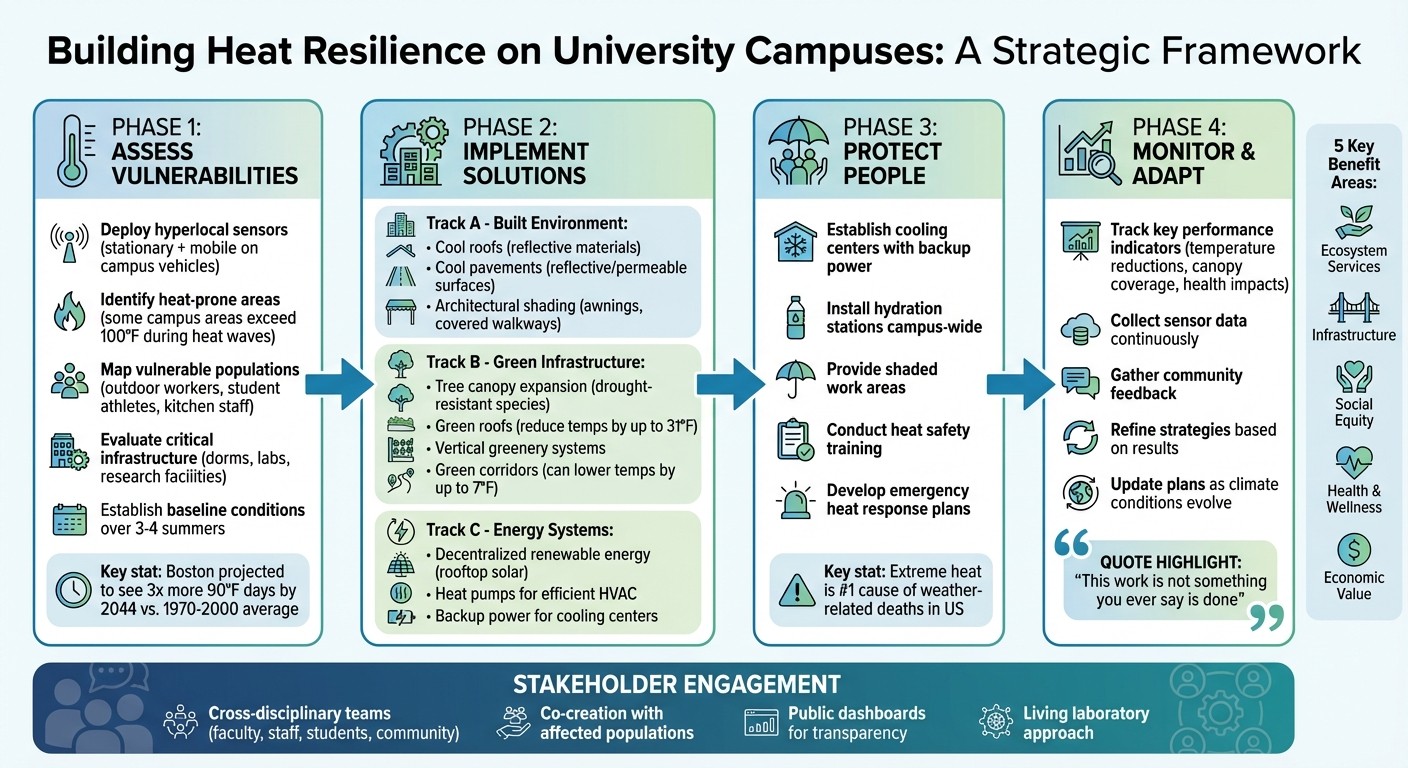

How to Build Heat Resilience & Urban Greening for Universities & Research Institutions

Universities face rising temperatures and urban heat islands that disrupt campus life, strain infrastructure, and endanger public health. Extreme heat impacts outdoor workers, student athletes, and infrastructure like dorms and labs. Projections indicate heat waves will intensify, with Boston seeing triple the 90°F days by 2044 compared to past decades.

To address these challenges, universities are adopting strategies such as:

Mapping Heat Risks: Using sensors for localized data to identify hotspots and vulnerable populations.

Green Infrastructure: Planting trees, installing green roofs, and using vegetation to cool campuses.

Energy Upgrades: Adding cool roofs, reflective pavements, and renewable energy systems to reduce heat absorption.

Cooling Centers: Preparing air-conditioned spaces for heat waves, with backup power and accessible resources.

Worker Safety: Providing hydration stations, shaded areas, and heat safety training for outdoor staff.

Collaborative Planning: Engaging students, staff, and local communities to prioritize solutions.

Long-term efforts include climate-adaptive landscaping, sustainable transportation systems, and continuous monitoring to refine strategies over time. These measures not only protect campus communities but also serve as models for broader urban resilience.

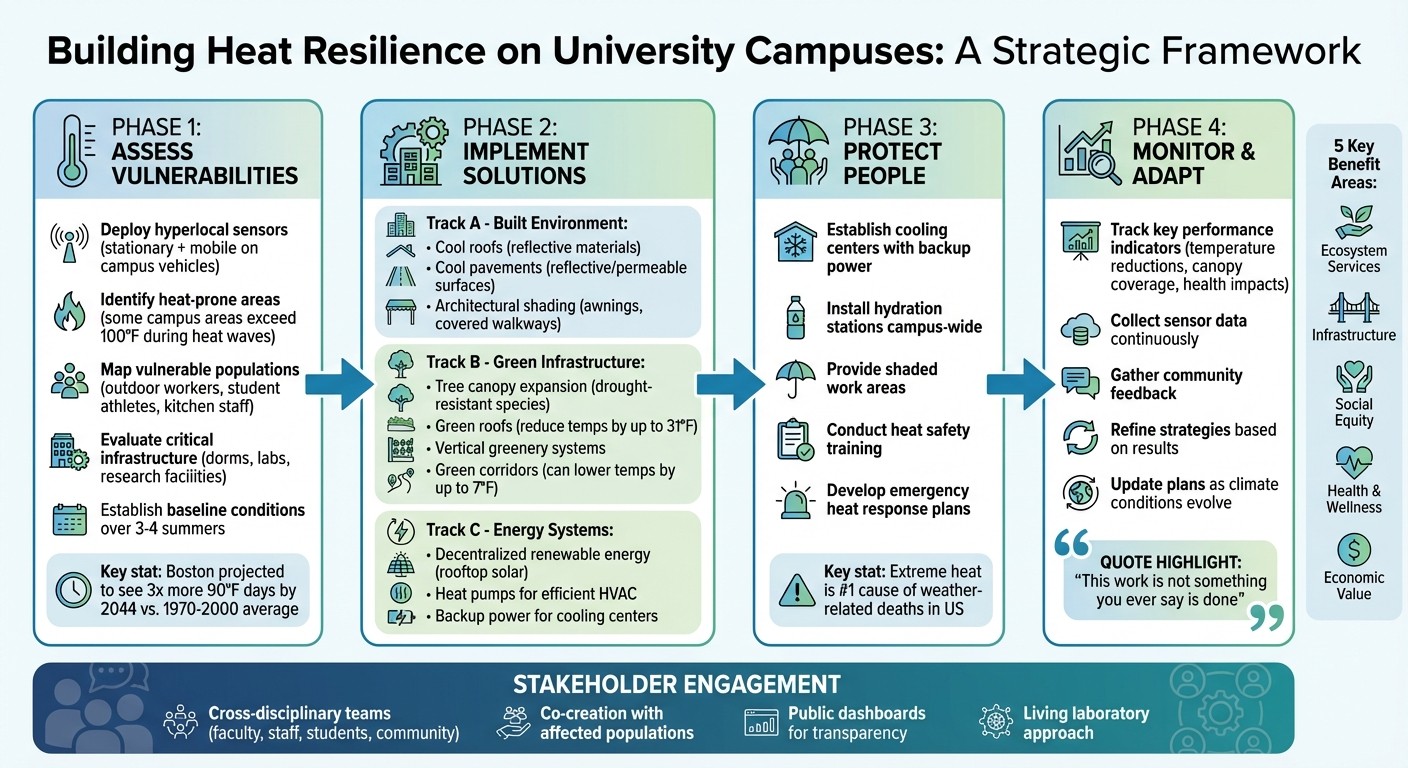

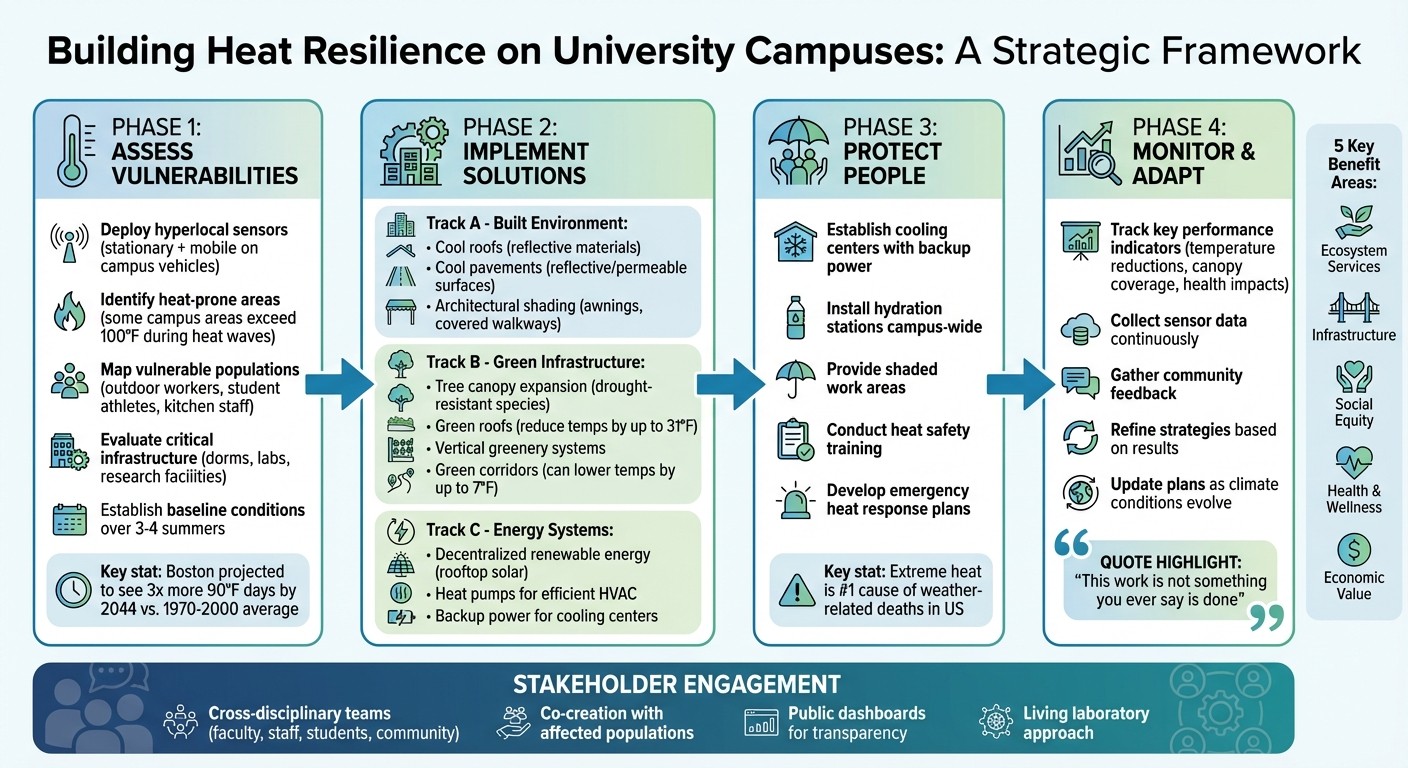

University Heat Resilience Implementation Framework: Assessment to Action

Building Urban Resilience – Session 3 from the Urban & Heat Learning Journey

How to Assess Campus Heat Vulnerability and Climate Risks

To effectively implement strategies for resilience, campuses must first conduct detailed mapping of extreme heat. This requires hyperlocal data that captures the unique microclimates created by buildings, pavement, and vegetation. Such assessments form the foundation for precise and impactful heat resilience measures.

How to Identify Heat-Prone Areas and Climate Hazards

Utilizing a combination of stationary and mobile sensors is key to gathering high-frequency, localized temperature data. In July 2024, MIT deployed sensors across its campus and on recycling trucks, uncovering that certain areas consistently recorded temperatures over 100°F - significantly higher than readings from regional weather stations[3].

Graduate student Sanjana Paul explained:

"Urban environmental phenomena are hyperlocal. While National Weather Service readouts at locations like Logan Airport are extremely valuable, this gives us a detailed understanding of campus microclimates."[3]

To expand sensor networks affordably, universities can involve engineering students in designing and building custom sensors. For example, MIT's "Engineering for Impact" course enabled students to create specialized heat sensors, which not only enhanced data collection but also provided hands-on educational opportunities. The collected data is then integrated into a Climate Resiliency Dashboard, offering a clear visualization of building-level impacts and helping planners identify high-priority areas.

Laura Tenny, Senior Campus Planner at MIT, highlighted the challenges of mapping heat:

"Heat also doesn't conform to topography like flooding, making it harder to map it with localized specificity. Microclimates, humidity levels, shade or sun aspect, and other factors contribute to heat risk."[3]

To reliably identify hotspots, institutions should gather data over three to four summers. For instance, in July 2023, the University of Texas at Arlington hosted design charrettes where faculty, students, and staff collaborated to locate heat-prone areas and create a prioritization matrix. This matrix incorporated watershed locations alongside ecological and community factors[6].

How to Evaluate Vulnerable Populations and Infrastructure

Mapping heat-prone areas is just one step; universities also need to assess who and what is most vulnerable. Brian Goldberg, Assistant Director of MIT's Office of Sustainability, emphasized:

"While stress on campus infrastructure is one factor we are evaluating, our primary focus is the vulnerability of people to extreme heat."[3]

To identify at-risk groups, universities should focus on roles with high heat exposure - such as maintenance crews, kitchen staff, and student athletes. This evaluation can be guided by four factors: social and environmental conditions, isolation, access to air conditioning, and the prevalence of chronic health conditions[8].

Susy Jones, Senior Sustainability Project Manager at MIT, reflected on the equity aspects of heat vulnerability:

"We know that people on our campus are already experiencing these extreme heat days differently. We need to design strategies and augment existing interventions with equity in mind."[3]

In addition to human vulnerability, institutions must assess critical infrastructure such as dormitories and research laboratories. Effective temperature control in these spaces is vital for safety and operational continuity. A thorough evaluation should consider five dimensions: Ecosystem Services, Infrastructure, Social Equity and Governance, Health and Wellness, and Economic factors[7].

How to Document Baseline Conditions

Establishing baseline conditions requires combining sensor data with community surveys to capture the lived experiences of heat impacts.

Universities should centralize this information on digital platforms for better organization and analysis. For example, MIT's Climate Resiliency Dashboard integrates heat risk data with other climate hazards, such as flooding, offering planners a comprehensive view of vulnerabilities. These dashboards must remain adaptable, evolving as new data becomes available, to ensure resilience mapping is an ongoing process[7].

Baseline documentation also involves evaluating the institution's current adaptive capacity - the ability to adjust to climate challenges and reduce potential damages. By collecting both environmental data and community feedback over multiple years, universities can create a solid foundation for effective, targeted heat resilience strategies.

Heat Mitigation Strategies for University Campuses

When universities assess their heat vulnerabilities, they can take specific steps to lower temperatures and improve comfort across campus. These efforts typically fall into three main areas: improving the built environment, introducing green infrastructure, and refining energy systems.

Cooling the Built Environment

One of the most effective ways to address heat at the building level is through cool roofs. These roofs use materials that reflect sunlight and release heat more effectively than traditional roofing, reducing heat buildup.

In addition to roofs, universities can adopt cool pavements for parking lots and pedestrian pathways. Materials designed to reflect sunlight or allow water to pass through can significantly cut down on heat absorption in these frequently used spaces. Adding architectural shading, such as covered walkways, awnings, or extended building overhangs, also improves outdoor comfort by providing relief from direct sunlight.

Incorporating these updates into routine capital improvement projects ensures that heat mitigation becomes a long-term commitment rather than a series of standalone fixes. Pairing these structural upgrades with natural cooling methods further amplifies their impact.

Green Infrastructure Solutions

Tree canopies offer immediate relief by shading surfaces and cooling the surrounding air through evapotranspiration. Planting drought-resistant, dense-canopy trees along busy walkways and near building entrances can maximize their cooling effects. However, careful planning is essential to ensure tree roots don’t interfere with nearby rain gardens or bioswales.

Another effective strategy is green roofs, which cool buildings by reducing rooftop temperatures through evapotranspiration. Studies show that green roofs can lower rooftop temperatures by as much as 31°F compared to conventional roofs[9]. Universities often offset the costs of these installations by tapping into local rebate programs, like the District of Columbia's RiverSmart Rooftops program or Philadelphia's Green Roof Tax Credit Program[1].

For campuses with limited ground space, vertical greenery systems (like green walls) and blue-green infrastructure - which combines water features with vegetation - can provide cooling benefits. By creating green corridors that align with local wind patterns, universities can enhance airflow and redistribute heat, potentially lowering temperatures by up to 7°F[9].

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Systems

Reducing heat starts with cutting energy use. Universities can install decentralized renewable energy systems, such as rooftop solar panels, which not only generate clean energy but also shade buildings and reduce heat absorption. Heat pumps are another option, offering efficient heating and cooling while producing less waste heat than traditional HVAC systems[1].

UC Davis serves as an example of integrating energy-efficient practices with climate adaptation. Their 70-year "Living Landscape Adaptation Plan" merges horticultural science with sustainable infrastructure to prepare the campus for future climate challenges. As UC Davis Campus Planning explains:

"The UC Davis campus can become a demonstration project integrating good science, community building and teamwork that will become a model for universities and institutions facing the same threats."[4]

Universities also act as testing grounds for broader solutions. In March 2023, sustainability leaders from colleges across all 50 states, including MIT’s Julie Newman, gathered to explore ways campus-scale climate initiatives could inspire changes in surrounding communities[5]. This collaborative approach not only benefits individual campuses but also supports regional efforts to tackle climate challenges.

How to Protect People from Extreme Heat

While long-term infrastructure upgrades can help reduce campus temperatures, universities must also be ready with immediate strategies to safeguard people during heat waves. Extreme heat is the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the United States, making it critical for campuses to act swiftly and effectively during such events[11]. These measures build on earlier discussions of heat resilience and vulnerability assessments, ensuring that campuses are equipped to protect their communities when temperatures soar.

How to Establish Cooling Centers

Cooling centers provide a vital refuge during heat waves. Universities should identify and prepare campus buildings, such as libraries, student centers, or recreation facilities, that already have air conditioning and extended hours. To ensure these spaces remain functional even during power outages, they should be equipped with backup energy systems or microgrids[11].

Location is a key factor in the success of cooling centers. For example, in July 2023, the University of Texas at Arlington collaborated with the US EPA to create a prioritization matrix, helping determine where cooling interventions would best serve populations based on heat exposure and community needs[6]. Research in Los Angeles County revealed that while only 20% of people used official cooling centers during heat events, 90% sought informal options like shopping malls[10]. Universities can adapt by extending hours at campus pools and other air-conditioned areas to meet these preferences.

Cooling centers should offer more than just a cool environment. They need to provide shade, drinking water, restrooms, and clear multilingual signage. Groups most at risk include those without air conditioning at home, outdoor workers, individuals with chronic health conditions, and people living alone[10][11]. Additionally, formerly redlined neighborhoods often experience temperatures up to 7.5°F hotter during the day and 3.6°F hotter at night compared to other areas, highlighting the need for targeted support in these communities[11].

These efforts lay the groundwork for addressing the needs of vulnerable groups, including outdoor workers, as explored in the next section.

Outdoor Worker Protection and Heat Safety Protocols

Certain campus groups, such as maintenance crews, groundskeepers, kitchen staff, and student-athletes, face heightened risks due to prolonged outdoor activity in the heat. To protect these workers, universities should implement measures like hydration stations across campus, mandatory water breaks during peak heat hours, and shaded workspaces, which can include temporary canopies or permanent structures.

Training is essential to ensure workers can recognize and respond to heat illness symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, and confusion[2]. The first heat wave of the season is often the most dangerous because individuals have not yet acclimated to the high temperatures[2]. For example, Toronto Public Health holds an annual media day in May to educate the public about heat risks before summer begins[2]. Universities could adopt similar strategies by hosting campus-wide training sessions in late spring to prepare their communities.

These immediate actions complement broader heat response efforts, which should be integrated into campus emergency planning.

How to Develop Campus Emergency Heat Plans

Emergency heat plans should be woven into existing campus emergency frameworks. For instance, in July 2024, MIT's Office of Sustainability used heat sensors on tripods and recycling trucks to map campus microclimates where temperatures exceeded 100°F. This data informed their Climate Resiliency and Adaptation Roadmap, helping determine where new cooling centers were most needed[3].

Successful emergency plans require collaboration across departments. Universities should form cross-functional teams involving Sustainability, Emergency Management, Facilities, and Health Services to ensure resources are prepared before heat waves hit. This might include distributing cooling towels, setting up portable shade structures, and ensuring communication systems reach everyone, including those with language barriers or limited mobility[11].

Chicago’s experience highlights the importance of comprehensive planning. After a devastating heat wave in 1995 caused around 700 deaths, the city launched its first heat notification and response program in partnership with the National Weather Service. This initiative reduced heat-related deaths to approximately 100 by 1999[2]. Universities can achieve similar outcomes by monitoring 5-day weather forecasts, activating early warning systems, and providing resource guides - complete with utility assistance information and cooling center details in multiple languages[2][11].

Climate-Resilient Landscaping and Transportation Planning

Long-term planning for landscapes and transportation systems can reshape campuses into cooler, more sustainable spaces while complementing immediate heat mitigation efforts. Below, we delve into strategies like urban greening and transportation planning that bolster campus resilience.

Urban Greening and Climate-Adaptive Landscaping

Universities must rethink their campus landscapes to prepare for future climate conditions. A prime example is UC Davis's 70-year Living Landscape Adaptation Plan, which focuses on transitioning to drought-resistant native plants. This shift not only protects campus ecosystems but also addresses the vulnerability of horticultural plants that struggle when grown far outside their native habitats [4].

This initiative highlights the importance of combining research with community collaboration to tackle climate challenges:

"The UC Davis campus can become a demonstration project integrating good science, community building and teamwork that will become a model for universities and institutions facing the same threats while planning for the climate of tomorrow." - UC Davis [4]

To build resilience, campuses should expand tree canopies, incorporate drought-tolerant species, and gradually introduce plants suited to changing climates. Universities can act as living laboratories, testing innovative solutions on campus before applying them to surrounding areas [4][5]. In March 2023, sustainability leaders from colleges across all 50 states convened to exchange ideas on campus-scale climate strategies. Their insights were later compiled in a June 2024 report, offering actionable steps for other institutions [5].

Sustainable Transportation Infrastructure

Shaded walkways and bike paths, when paired with green infrastructure, can address both heat and stormwater challenges. Designing such systems requires a deep understanding of campus watershed dynamics and the interplay between transportation networks and the environment [6]. Rather than treating these as isolated projects, universities should integrate them into broader master plans that tackle multiple climate issues at once. Water management techniques, for example, naturally complement these transportation upgrades.

Stormwater Management for Heat Resilience

Building on green infrastructure, stormwater management plays a key role in addressing both heat and flooding. By managing rainwater where it falls, green solutions reduce flood risks while cooling the environment through vegetation and moisture retention [6]. In July 2023, the University of Texas at Arlington released a Green Infrastructure Report after working with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the Campus RainWorks Challenge. The effort included a collaborative design session where students, faculty, and staff developed strategies for rainwater management and heat mitigation. The resulting prioritization matrix now guides future campus investments [6].

"Investing in green infrastructure is critical for managing stormwater and heat stress today and addressing the emerging challenges caused by a changing climate: shifting precipitation patterns, 'cloudbursts' or flash floods, and more frequent and severe extreme heat events." - Center for Metropolitan Density, UTA Office of Facilities Management et al. [6]

To enhance resilience, universities can strategically incorporate bioswales, permeable pavements, and rain gardens based on watershed dynamics and ecological requirements. Incorporating cloudburst visioning into master plans ensures infrastructure can withstand sudden, heavy rainfall while supporting broader goals for heat resilience [6].

How to Engage Stakeholders and Build Institutional Support

Engaging stakeholders is essential for driving heat resilience strategies and urban greening efforts that safeguard campus communities. Success hinges on securing support from a broad range of campus and community groups, each contributing unique insights and expertise. Without intentional collaboration, even the most carefully planned initiatives risk falling short due to lack of alignment with community priorities or insufficient backing.

Identifying and Engaging Stakeholder Groups

Start by forming a cross-disciplinary team that includes faculty, staff, students, and external partners such as public health officials and city planners [12][14]. Focus on engaging those most affected by extreme heat, ensuring their voices shape the project from the outset.

Move beyond traditional surveys to a model of community co-creation. This inclusive approach allows stakeholders to actively participate in planning and design, addressing past inequities like redlining, which left certain areas with fewer green spaces and higher heat risks. It also helps avoid unintended consequences, such as green gentrification [12][13]. As Olivia J. Keenan and her colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine emphasize:

"Urban greening interventions are often implemented without input from communities, which can result in vegetation planted in unwelcome locations" [12].

A 2022 study by Hopkins et al. offers a strong example of this approach. Researchers used health data, such as rates of cardiac arrest and asthma attacks, to prioritize tree planting in areas with the greatest need. This strategy ensured that interventions directly benefitted the most vulnerable populations [12]. Such collaborative efforts naturally foster ongoing dialogue and partnership.

Designing Collaborative Planning Processes

Creating meaningful collaboration requires consistent engagement, not just occasional meetings. Many institutions have used this approach to guide successful planning. For instance, in July 2024, MIT’s Office of Sustainability advanced its Climate Resiliency and Adaptation Roadmap by combining data from various research labs, while students in Course 6.900 deployed heat sensors across campus [3]. Assistant Director Brian Goldberg highlighted the importance of blending data with lived experiences:

"The data tells an important story, but individuals help us complete the picture" [3].

Establish a Resilience Planning Working Group to bring together diverse perspectives. This team should include facilities management staff (to assess operational feasibility), faculty (to provide technical and academic expertise), students (who experience campus conditions firsthand), and local community members (who share similar heat-related challenges) [12][13].

Communicating the Benefits of Resilience and Greening

Once stakeholder engagement and planning are underway, clear communication about the benefits of resilience and urban greening can solidify institutional support. Frame heat resilience as a core part of your mission rather than an optional initiative. Julie Newman, MIT’s Director of Sustainability, articulated this approach:

"We seek to identify solutions for our own campus in a manner that others can learn from and potentially adapt for their own resiliency and climate planning purposes" [3].

Use building-level data to expose hidden heat risks. For example, climate models predict that days exceeding 90°F could triple compared to the 1970–2000 average, with some campus areas surpassing 100°F during heat waves [3]. A public dashboard mapping heat and flood risks to campus assets can help decision-makers visualize how extreme temperatures threaten operations and community health.

Communicate benefits across five key dimensions: natural cooling and stormwater management (ecosystem services), infrastructure protection, equity and governance, health and wellness, and financial value [7]. For instance, shaded areas can be up to 36°F cooler than unshaded ones during heat waves, while vegetation’s evapotranspiration can lower air temperatures by 2°F to 14°F [12]. Position your campus as a living laboratory where research, community engagement, and curriculum intersect. This approach not only attracts funding for research but also showcases solutions that other institutions can replicate [4][6].

How to Monitor Progress and Adapt to Changing Conditions

Heat resilience planning is never a one-and-done effort. As Brian Goldberg aptly puts it:

"This work is not something you ever say is done. As information and data evolves, so does our work" [3].

To keep pace with shifting climate conditions and the emergence of new data, campuses must adopt systematic tracking methods and remain flexible in their strategies. Establishing clear performance indicators is a crucial step to ensure progress and refine efforts over time.

How to Define Key Performance Indicators

Key metrics should focus on environmental changes, infrastructure performance, and social impacts. For example, monitor microclimate temperature reductions in heat-prone areas, increases in tree canopy coverage, and expanded shaded zones across the campus. Operational metrics might include energy usage during heatwaves or signs of infrastructure strain. Equally important are social equity indicators, such as tracking heat-related health issues among vulnerable groups like outdoor maintenance workers, kitchen staff, and student athletes. Gathering direct feedback from these groups about their working conditions adds an invaluable human perspective.

UC Davis exemplifies this long-term vision through its Living Landscape Adaptation Plan, a 70-year roadmap aimed at transforming the campus into a "climate-ready" landscape [4]. This approach recognizes that true resilience requires not only immediate action but also sustained monitoring and flexibility as conditions evolve.

How to Collect and Analyze Performance Data

Local sensor networks play a key role in capturing precise, high-resolution data. For instance, MIT employs compact sensors mounted on tripods and recycling trucks to measure urban microclimates [3]. These localized readings are essential because, as Sanjana Paul from MIT's Senseable City Lab explains:

"Urban environmental phenomena are hyperlocal. While National Weather Service readouts... are extremely valuable, this gives us a more high-resolution understanding of the urban microclimate on our campus" [3].

Equipping campus service vehicles with sensors can provide comprehensive coverage of the campus environment. MIT's initiative, involving the Urban Risk Lab, Senseable City Lab, and students from course 6.900 (Engineering for Impact), uncovered that campus temperatures during heatwaves often exceeded 100°F - far higher than regional airport data suggested [3]. Centralizing this information in a public-facing dashboard makes it easier to inform planning decisions and engage the campus community. Combining this quantitative data with qualitative feedback from campus users about their heat-related experiences ensures a more complete understanding of the challenges.

With robust data collection in place, campuses can identify problem areas and fine-tune their strategies for maximum effectiveness.

How to Refine Strategies Based on Results

Data analysis helps pinpoint areas needing immediate attention. For example, if certain buildings or outdoor spaces consistently exceed safe temperature thresholds, those locations should be prioritized for cooling centers or green infrastructure investments. UT Arlington’s prioritization matrix [6] offers a practical example of how ecological, economic, and community considerations can guide targeted interventions.

Addressing equity gaps is equally critical. If data reveals that certain groups face disproportionate heat exposure, strategies should be adjusted accordingly. Using tools like the WBGT index, which factors in humidity, wind, and sunlight, provides a more accurate measure of heat stress than air temperature alone [15].

Treat your resilience plan as a dynamic document that evolves with new data, updated climate projections, and changing community needs. For instance, climate models for Cambridge project that the number of days above 90°F could triple between 2015 and 2044 compared to the 1970–2000 average [3]. This makes ongoing adaptation not just beneficial but essential.

Conclusion

Addressing heat resilience and promoting urban greening are critical steps for safeguarding campus communities and ensuring academic missions remain uninterrupted. Achieving this requires a foundation of detailed baseline data, collaborative efforts, and flexible, ongoing strategies.

Start by analyzing your campus's specific heat challenges through precise, hyperlocal monitoring. Identify groups most vulnerable to extreme heat, such as outdoor staff and student athletes, to prioritize targeted actions. University leaders emphasize the importance of solutions that are both locally tailored and adaptable to other settings.

Pair immediate measures - like creating cooling centers and implementing heat safety protocols - with longer-term investments in infrastructure. These efforts should be part of a broader strategy that balances urgent needs with preparations for future climate realities.

Collaboration is the backbone of any successful resilience strategy. By involving faculty, students, staff, facilities teams, and local government, you can bridge the gap between technical data and real-world experiences. Tools like accessible dashboards can make climate risks clear to everyone while encouraging input from those directly affected by heat.

FAQs

How can universities identify and address heat-prone areas on campus?

Universities can tackle heat-prone areas on campus by leveraging data-driven tools and fostering collaborative efforts. Geographic information system (GIS) mapping serves as a powerful tool to identify hotspots, such as zones with limited vegetation or surfaces that absorb and retain heat. These maps reveal patterns like urban heat island effects and surface temperature differences, helping institutions pinpoint areas that require immediate attention.

Using real-time data from heat sensors and remote sensing technology adds another layer of precision, offering a detailed understanding of heat vulnerabilities across campus. Universities can further enrich their analysis by partnering with local agencies and incorporating feedback from the campus community. This combination of advanced tools and shared knowledge can guide effective solutions, such as planting trees, installing shade structures, or upgrading infrastructure to minimize heat exposure and improve campus resilience.

What are the best ways to protect at-risk groups during extreme heat events?

Protecting those most at risk during extreme heat events calls for a combination of planning, community involvement, and smart infrastructure. Early warning systems and public education play a key role in alerting people to heat dangers, recognizing signs of heat-related illnesses, and learning practical ways to stay safe. Ensuring access to cooling centers or air-conditioned spaces is crucial for safeguarding vulnerable groups, such as older adults, young children, and individuals with chronic health conditions.

Efforts that focus on the community, like identifying high-risk populations and creating targeted solutions, are equally important. Expanding urban tree canopies, adding more shaded areas, and using green infrastructure help reduce local temperatures while offering natural cooling benefits. Together, these measures create a proactive approach to protecting the most vulnerable during intense heat waves.

How can universities use green infrastructure to stay cooler and more sustainable?

Universities have a significant opportunity to address heat challenges and promote ecological health by integrating green infrastructure into their campuses. Initiatives such as planting shade trees, installing green roofs, and incorporating permeable surfaces help reduce urban heat, improve air quality, and manage stormwater more efficiently.

Creating shaded outdoor areas and expanding tree canopies further enhances campus comfort by offering cooler spaces for students, staff, and visitors. When combined with careful planning and collaboration among stakeholders, these strategies can be tailored to meet the specific needs of each campus. By embracing these nature-focused solutions, universities can foster environments that are both resilient to heat and supportive of long-term ecological balance.

Related Blog Posts

How to Build a Climate Resilience Plan for Universities & Research Institutions

How to Integrate Climate Risk into Infrastructure Planning for Universities & Research Institutions

How to Build Heat Resilience & Urban Greening for Municipalities & Government Agencies

How to Build Heat Resilience & Urban Greening for Corporations

Latest Articles

©2025

FAQ

FAQ

01

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

02

What makes Council Fire different?

03

Who does Council Fire you work with?

04

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

05

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

06

How does Council Fire define and measure success?

01

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

02

What makes Council Fire different?

03

Who does Council Fire you work with?

04

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

05

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

06

How does Council Fire define and measure success?

Feb 1, 2026

How to Build Heat Resilience & Urban Greening for Universities & Research Institutions

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Actionable guidance for universities to map heat risks, expand urban greening, set up cooling centers, protect vulnerable groups, and monitor outcomes.

How to Build Heat Resilience & Urban Greening for Universities & Research Institutions

Universities face rising temperatures and urban heat islands that disrupt campus life, strain infrastructure, and endanger public health. Extreme heat impacts outdoor workers, student athletes, and infrastructure like dorms and labs. Projections indicate heat waves will intensify, with Boston seeing triple the 90°F days by 2044 compared to past decades.

To address these challenges, universities are adopting strategies such as:

Mapping Heat Risks: Using sensors for localized data to identify hotspots and vulnerable populations.

Green Infrastructure: Planting trees, installing green roofs, and using vegetation to cool campuses.

Energy Upgrades: Adding cool roofs, reflective pavements, and renewable energy systems to reduce heat absorption.

Cooling Centers: Preparing air-conditioned spaces for heat waves, with backup power and accessible resources.

Worker Safety: Providing hydration stations, shaded areas, and heat safety training for outdoor staff.

Collaborative Planning: Engaging students, staff, and local communities to prioritize solutions.

Long-term efforts include climate-adaptive landscaping, sustainable transportation systems, and continuous monitoring to refine strategies over time. These measures not only protect campus communities but also serve as models for broader urban resilience.

University Heat Resilience Implementation Framework: Assessment to Action

Building Urban Resilience – Session 3 from the Urban & Heat Learning Journey

How to Assess Campus Heat Vulnerability and Climate Risks

To effectively implement strategies for resilience, campuses must first conduct detailed mapping of extreme heat. This requires hyperlocal data that captures the unique microclimates created by buildings, pavement, and vegetation. Such assessments form the foundation for precise and impactful heat resilience measures.

How to Identify Heat-Prone Areas and Climate Hazards

Utilizing a combination of stationary and mobile sensors is key to gathering high-frequency, localized temperature data. In July 2024, MIT deployed sensors across its campus and on recycling trucks, uncovering that certain areas consistently recorded temperatures over 100°F - significantly higher than readings from regional weather stations[3].

Graduate student Sanjana Paul explained:

"Urban environmental phenomena are hyperlocal. While National Weather Service readouts at locations like Logan Airport are extremely valuable, this gives us a detailed understanding of campus microclimates."[3]

To expand sensor networks affordably, universities can involve engineering students in designing and building custom sensors. For example, MIT's "Engineering for Impact" course enabled students to create specialized heat sensors, which not only enhanced data collection but also provided hands-on educational opportunities. The collected data is then integrated into a Climate Resiliency Dashboard, offering a clear visualization of building-level impacts and helping planners identify high-priority areas.

Laura Tenny, Senior Campus Planner at MIT, highlighted the challenges of mapping heat:

"Heat also doesn't conform to topography like flooding, making it harder to map it with localized specificity. Microclimates, humidity levels, shade or sun aspect, and other factors contribute to heat risk."[3]

To reliably identify hotspots, institutions should gather data over three to four summers. For instance, in July 2023, the University of Texas at Arlington hosted design charrettes where faculty, students, and staff collaborated to locate heat-prone areas and create a prioritization matrix. This matrix incorporated watershed locations alongside ecological and community factors[6].

How to Evaluate Vulnerable Populations and Infrastructure

Mapping heat-prone areas is just one step; universities also need to assess who and what is most vulnerable. Brian Goldberg, Assistant Director of MIT's Office of Sustainability, emphasized:

"While stress on campus infrastructure is one factor we are evaluating, our primary focus is the vulnerability of people to extreme heat."[3]

To identify at-risk groups, universities should focus on roles with high heat exposure - such as maintenance crews, kitchen staff, and student athletes. This evaluation can be guided by four factors: social and environmental conditions, isolation, access to air conditioning, and the prevalence of chronic health conditions[8].

Susy Jones, Senior Sustainability Project Manager at MIT, reflected on the equity aspects of heat vulnerability:

"We know that people on our campus are already experiencing these extreme heat days differently. We need to design strategies and augment existing interventions with equity in mind."[3]

In addition to human vulnerability, institutions must assess critical infrastructure such as dormitories and research laboratories. Effective temperature control in these spaces is vital for safety and operational continuity. A thorough evaluation should consider five dimensions: Ecosystem Services, Infrastructure, Social Equity and Governance, Health and Wellness, and Economic factors[7].

How to Document Baseline Conditions

Establishing baseline conditions requires combining sensor data with community surveys to capture the lived experiences of heat impacts.

Universities should centralize this information on digital platforms for better organization and analysis. For example, MIT's Climate Resiliency Dashboard integrates heat risk data with other climate hazards, such as flooding, offering planners a comprehensive view of vulnerabilities. These dashboards must remain adaptable, evolving as new data becomes available, to ensure resilience mapping is an ongoing process[7].

Baseline documentation also involves evaluating the institution's current adaptive capacity - the ability to adjust to climate challenges and reduce potential damages. By collecting both environmental data and community feedback over multiple years, universities can create a solid foundation for effective, targeted heat resilience strategies.

Heat Mitigation Strategies for University Campuses

When universities assess their heat vulnerabilities, they can take specific steps to lower temperatures and improve comfort across campus. These efforts typically fall into three main areas: improving the built environment, introducing green infrastructure, and refining energy systems.

Cooling the Built Environment

One of the most effective ways to address heat at the building level is through cool roofs. These roofs use materials that reflect sunlight and release heat more effectively than traditional roofing, reducing heat buildup.

In addition to roofs, universities can adopt cool pavements for parking lots and pedestrian pathways. Materials designed to reflect sunlight or allow water to pass through can significantly cut down on heat absorption in these frequently used spaces. Adding architectural shading, such as covered walkways, awnings, or extended building overhangs, also improves outdoor comfort by providing relief from direct sunlight.

Incorporating these updates into routine capital improvement projects ensures that heat mitigation becomes a long-term commitment rather than a series of standalone fixes. Pairing these structural upgrades with natural cooling methods further amplifies their impact.

Green Infrastructure Solutions

Tree canopies offer immediate relief by shading surfaces and cooling the surrounding air through evapotranspiration. Planting drought-resistant, dense-canopy trees along busy walkways and near building entrances can maximize their cooling effects. However, careful planning is essential to ensure tree roots don’t interfere with nearby rain gardens or bioswales.

Another effective strategy is green roofs, which cool buildings by reducing rooftop temperatures through evapotranspiration. Studies show that green roofs can lower rooftop temperatures by as much as 31°F compared to conventional roofs[9]. Universities often offset the costs of these installations by tapping into local rebate programs, like the District of Columbia's RiverSmart Rooftops program or Philadelphia's Green Roof Tax Credit Program[1].

For campuses with limited ground space, vertical greenery systems (like green walls) and blue-green infrastructure - which combines water features with vegetation - can provide cooling benefits. By creating green corridors that align with local wind patterns, universities can enhance airflow and redistribute heat, potentially lowering temperatures by up to 7°F[9].

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Systems

Reducing heat starts with cutting energy use. Universities can install decentralized renewable energy systems, such as rooftop solar panels, which not only generate clean energy but also shade buildings and reduce heat absorption. Heat pumps are another option, offering efficient heating and cooling while producing less waste heat than traditional HVAC systems[1].

UC Davis serves as an example of integrating energy-efficient practices with climate adaptation. Their 70-year "Living Landscape Adaptation Plan" merges horticultural science with sustainable infrastructure to prepare the campus for future climate challenges. As UC Davis Campus Planning explains:

"The UC Davis campus can become a demonstration project integrating good science, community building and teamwork that will become a model for universities and institutions facing the same threats."[4]

Universities also act as testing grounds for broader solutions. In March 2023, sustainability leaders from colleges across all 50 states, including MIT’s Julie Newman, gathered to explore ways campus-scale climate initiatives could inspire changes in surrounding communities[5]. This collaborative approach not only benefits individual campuses but also supports regional efforts to tackle climate challenges.

How to Protect People from Extreme Heat

While long-term infrastructure upgrades can help reduce campus temperatures, universities must also be ready with immediate strategies to safeguard people during heat waves. Extreme heat is the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the United States, making it critical for campuses to act swiftly and effectively during such events[11]. These measures build on earlier discussions of heat resilience and vulnerability assessments, ensuring that campuses are equipped to protect their communities when temperatures soar.

How to Establish Cooling Centers

Cooling centers provide a vital refuge during heat waves. Universities should identify and prepare campus buildings, such as libraries, student centers, or recreation facilities, that already have air conditioning and extended hours. To ensure these spaces remain functional even during power outages, they should be equipped with backup energy systems or microgrids[11].

Location is a key factor in the success of cooling centers. For example, in July 2023, the University of Texas at Arlington collaborated with the US EPA to create a prioritization matrix, helping determine where cooling interventions would best serve populations based on heat exposure and community needs[6]. Research in Los Angeles County revealed that while only 20% of people used official cooling centers during heat events, 90% sought informal options like shopping malls[10]. Universities can adapt by extending hours at campus pools and other air-conditioned areas to meet these preferences.

Cooling centers should offer more than just a cool environment. They need to provide shade, drinking water, restrooms, and clear multilingual signage. Groups most at risk include those without air conditioning at home, outdoor workers, individuals with chronic health conditions, and people living alone[10][11]. Additionally, formerly redlined neighborhoods often experience temperatures up to 7.5°F hotter during the day and 3.6°F hotter at night compared to other areas, highlighting the need for targeted support in these communities[11].

These efforts lay the groundwork for addressing the needs of vulnerable groups, including outdoor workers, as explored in the next section.

Outdoor Worker Protection and Heat Safety Protocols

Certain campus groups, such as maintenance crews, groundskeepers, kitchen staff, and student-athletes, face heightened risks due to prolonged outdoor activity in the heat. To protect these workers, universities should implement measures like hydration stations across campus, mandatory water breaks during peak heat hours, and shaded workspaces, which can include temporary canopies or permanent structures.

Training is essential to ensure workers can recognize and respond to heat illness symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, and confusion[2]. The first heat wave of the season is often the most dangerous because individuals have not yet acclimated to the high temperatures[2]. For example, Toronto Public Health holds an annual media day in May to educate the public about heat risks before summer begins[2]. Universities could adopt similar strategies by hosting campus-wide training sessions in late spring to prepare their communities.

These immediate actions complement broader heat response efforts, which should be integrated into campus emergency planning.

How to Develop Campus Emergency Heat Plans

Emergency heat plans should be woven into existing campus emergency frameworks. For instance, in July 2024, MIT's Office of Sustainability used heat sensors on tripods and recycling trucks to map campus microclimates where temperatures exceeded 100°F. This data informed their Climate Resiliency and Adaptation Roadmap, helping determine where new cooling centers were most needed[3].

Successful emergency plans require collaboration across departments. Universities should form cross-functional teams involving Sustainability, Emergency Management, Facilities, and Health Services to ensure resources are prepared before heat waves hit. This might include distributing cooling towels, setting up portable shade structures, and ensuring communication systems reach everyone, including those with language barriers or limited mobility[11].

Chicago’s experience highlights the importance of comprehensive planning. After a devastating heat wave in 1995 caused around 700 deaths, the city launched its first heat notification and response program in partnership with the National Weather Service. This initiative reduced heat-related deaths to approximately 100 by 1999[2]. Universities can achieve similar outcomes by monitoring 5-day weather forecasts, activating early warning systems, and providing resource guides - complete with utility assistance information and cooling center details in multiple languages[2][11].

Climate-Resilient Landscaping and Transportation Planning

Long-term planning for landscapes and transportation systems can reshape campuses into cooler, more sustainable spaces while complementing immediate heat mitigation efforts. Below, we delve into strategies like urban greening and transportation planning that bolster campus resilience.

Urban Greening and Climate-Adaptive Landscaping

Universities must rethink their campus landscapes to prepare for future climate conditions. A prime example is UC Davis's 70-year Living Landscape Adaptation Plan, which focuses on transitioning to drought-resistant native plants. This shift not only protects campus ecosystems but also addresses the vulnerability of horticultural plants that struggle when grown far outside their native habitats [4].

This initiative highlights the importance of combining research with community collaboration to tackle climate challenges:

"The UC Davis campus can become a demonstration project integrating good science, community building and teamwork that will become a model for universities and institutions facing the same threats while planning for the climate of tomorrow." - UC Davis [4]

To build resilience, campuses should expand tree canopies, incorporate drought-tolerant species, and gradually introduce plants suited to changing climates. Universities can act as living laboratories, testing innovative solutions on campus before applying them to surrounding areas [4][5]. In March 2023, sustainability leaders from colleges across all 50 states convened to exchange ideas on campus-scale climate strategies. Their insights were later compiled in a June 2024 report, offering actionable steps for other institutions [5].

Sustainable Transportation Infrastructure

Shaded walkways and bike paths, when paired with green infrastructure, can address both heat and stormwater challenges. Designing such systems requires a deep understanding of campus watershed dynamics and the interplay between transportation networks and the environment [6]. Rather than treating these as isolated projects, universities should integrate them into broader master plans that tackle multiple climate issues at once. Water management techniques, for example, naturally complement these transportation upgrades.

Stormwater Management for Heat Resilience

Building on green infrastructure, stormwater management plays a key role in addressing both heat and flooding. By managing rainwater where it falls, green solutions reduce flood risks while cooling the environment through vegetation and moisture retention [6]. In July 2023, the University of Texas at Arlington released a Green Infrastructure Report after working with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the Campus RainWorks Challenge. The effort included a collaborative design session where students, faculty, and staff developed strategies for rainwater management and heat mitigation. The resulting prioritization matrix now guides future campus investments [6].

"Investing in green infrastructure is critical for managing stormwater and heat stress today and addressing the emerging challenges caused by a changing climate: shifting precipitation patterns, 'cloudbursts' or flash floods, and more frequent and severe extreme heat events." - Center for Metropolitan Density, UTA Office of Facilities Management et al. [6]

To enhance resilience, universities can strategically incorporate bioswales, permeable pavements, and rain gardens based on watershed dynamics and ecological requirements. Incorporating cloudburst visioning into master plans ensures infrastructure can withstand sudden, heavy rainfall while supporting broader goals for heat resilience [6].

How to Engage Stakeholders and Build Institutional Support

Engaging stakeholders is essential for driving heat resilience strategies and urban greening efforts that safeguard campus communities. Success hinges on securing support from a broad range of campus and community groups, each contributing unique insights and expertise. Without intentional collaboration, even the most carefully planned initiatives risk falling short due to lack of alignment with community priorities or insufficient backing.

Identifying and Engaging Stakeholder Groups

Start by forming a cross-disciplinary team that includes faculty, staff, students, and external partners such as public health officials and city planners [12][14]. Focus on engaging those most affected by extreme heat, ensuring their voices shape the project from the outset.

Move beyond traditional surveys to a model of community co-creation. This inclusive approach allows stakeholders to actively participate in planning and design, addressing past inequities like redlining, which left certain areas with fewer green spaces and higher heat risks. It also helps avoid unintended consequences, such as green gentrification [12][13]. As Olivia J. Keenan and her colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine emphasize:

"Urban greening interventions are often implemented without input from communities, which can result in vegetation planted in unwelcome locations" [12].

A 2022 study by Hopkins et al. offers a strong example of this approach. Researchers used health data, such as rates of cardiac arrest and asthma attacks, to prioritize tree planting in areas with the greatest need. This strategy ensured that interventions directly benefitted the most vulnerable populations [12]. Such collaborative efforts naturally foster ongoing dialogue and partnership.

Designing Collaborative Planning Processes

Creating meaningful collaboration requires consistent engagement, not just occasional meetings. Many institutions have used this approach to guide successful planning. For instance, in July 2024, MIT’s Office of Sustainability advanced its Climate Resiliency and Adaptation Roadmap by combining data from various research labs, while students in Course 6.900 deployed heat sensors across campus [3]. Assistant Director Brian Goldberg highlighted the importance of blending data with lived experiences:

"The data tells an important story, but individuals help us complete the picture" [3].

Establish a Resilience Planning Working Group to bring together diverse perspectives. This team should include facilities management staff (to assess operational feasibility), faculty (to provide technical and academic expertise), students (who experience campus conditions firsthand), and local community members (who share similar heat-related challenges) [12][13].

Communicating the Benefits of Resilience and Greening

Once stakeholder engagement and planning are underway, clear communication about the benefits of resilience and urban greening can solidify institutional support. Frame heat resilience as a core part of your mission rather than an optional initiative. Julie Newman, MIT’s Director of Sustainability, articulated this approach:

"We seek to identify solutions for our own campus in a manner that others can learn from and potentially adapt for their own resiliency and climate planning purposes" [3].

Use building-level data to expose hidden heat risks. For example, climate models predict that days exceeding 90°F could triple compared to the 1970–2000 average, with some campus areas surpassing 100°F during heat waves [3]. A public dashboard mapping heat and flood risks to campus assets can help decision-makers visualize how extreme temperatures threaten operations and community health.

Communicate benefits across five key dimensions: natural cooling and stormwater management (ecosystem services), infrastructure protection, equity and governance, health and wellness, and financial value [7]. For instance, shaded areas can be up to 36°F cooler than unshaded ones during heat waves, while vegetation’s evapotranspiration can lower air temperatures by 2°F to 14°F [12]. Position your campus as a living laboratory where research, community engagement, and curriculum intersect. This approach not only attracts funding for research but also showcases solutions that other institutions can replicate [4][6].

How to Monitor Progress and Adapt to Changing Conditions

Heat resilience planning is never a one-and-done effort. As Brian Goldberg aptly puts it:

"This work is not something you ever say is done. As information and data evolves, so does our work" [3].

To keep pace with shifting climate conditions and the emergence of new data, campuses must adopt systematic tracking methods and remain flexible in their strategies. Establishing clear performance indicators is a crucial step to ensure progress and refine efforts over time.

How to Define Key Performance Indicators

Key metrics should focus on environmental changes, infrastructure performance, and social impacts. For example, monitor microclimate temperature reductions in heat-prone areas, increases in tree canopy coverage, and expanded shaded zones across the campus. Operational metrics might include energy usage during heatwaves or signs of infrastructure strain. Equally important are social equity indicators, such as tracking heat-related health issues among vulnerable groups like outdoor maintenance workers, kitchen staff, and student athletes. Gathering direct feedback from these groups about their working conditions adds an invaluable human perspective.

UC Davis exemplifies this long-term vision through its Living Landscape Adaptation Plan, a 70-year roadmap aimed at transforming the campus into a "climate-ready" landscape [4]. This approach recognizes that true resilience requires not only immediate action but also sustained monitoring and flexibility as conditions evolve.

How to Collect and Analyze Performance Data

Local sensor networks play a key role in capturing precise, high-resolution data. For instance, MIT employs compact sensors mounted on tripods and recycling trucks to measure urban microclimates [3]. These localized readings are essential because, as Sanjana Paul from MIT's Senseable City Lab explains:

"Urban environmental phenomena are hyperlocal. While National Weather Service readouts... are extremely valuable, this gives us a more high-resolution understanding of the urban microclimate on our campus" [3].

Equipping campus service vehicles with sensors can provide comprehensive coverage of the campus environment. MIT's initiative, involving the Urban Risk Lab, Senseable City Lab, and students from course 6.900 (Engineering for Impact), uncovered that campus temperatures during heatwaves often exceeded 100°F - far higher than regional airport data suggested [3]. Centralizing this information in a public-facing dashboard makes it easier to inform planning decisions and engage the campus community. Combining this quantitative data with qualitative feedback from campus users about their heat-related experiences ensures a more complete understanding of the challenges.

With robust data collection in place, campuses can identify problem areas and fine-tune their strategies for maximum effectiveness.

How to Refine Strategies Based on Results

Data analysis helps pinpoint areas needing immediate attention. For example, if certain buildings or outdoor spaces consistently exceed safe temperature thresholds, those locations should be prioritized for cooling centers or green infrastructure investments. UT Arlington’s prioritization matrix [6] offers a practical example of how ecological, economic, and community considerations can guide targeted interventions.

Addressing equity gaps is equally critical. If data reveals that certain groups face disproportionate heat exposure, strategies should be adjusted accordingly. Using tools like the WBGT index, which factors in humidity, wind, and sunlight, provides a more accurate measure of heat stress than air temperature alone [15].

Treat your resilience plan as a dynamic document that evolves with new data, updated climate projections, and changing community needs. For instance, climate models for Cambridge project that the number of days above 90°F could triple between 2015 and 2044 compared to the 1970–2000 average [3]. This makes ongoing adaptation not just beneficial but essential.

Conclusion

Addressing heat resilience and promoting urban greening are critical steps for safeguarding campus communities and ensuring academic missions remain uninterrupted. Achieving this requires a foundation of detailed baseline data, collaborative efforts, and flexible, ongoing strategies.

Start by analyzing your campus's specific heat challenges through precise, hyperlocal monitoring. Identify groups most vulnerable to extreme heat, such as outdoor staff and student athletes, to prioritize targeted actions. University leaders emphasize the importance of solutions that are both locally tailored and adaptable to other settings.

Pair immediate measures - like creating cooling centers and implementing heat safety protocols - with longer-term investments in infrastructure. These efforts should be part of a broader strategy that balances urgent needs with preparations for future climate realities.

Collaboration is the backbone of any successful resilience strategy. By involving faculty, students, staff, facilities teams, and local government, you can bridge the gap between technical data and real-world experiences. Tools like accessible dashboards can make climate risks clear to everyone while encouraging input from those directly affected by heat.

FAQs

How can universities identify and address heat-prone areas on campus?

Universities can tackle heat-prone areas on campus by leveraging data-driven tools and fostering collaborative efforts. Geographic information system (GIS) mapping serves as a powerful tool to identify hotspots, such as zones with limited vegetation or surfaces that absorb and retain heat. These maps reveal patterns like urban heat island effects and surface temperature differences, helping institutions pinpoint areas that require immediate attention.

Using real-time data from heat sensors and remote sensing technology adds another layer of precision, offering a detailed understanding of heat vulnerabilities across campus. Universities can further enrich their analysis by partnering with local agencies and incorporating feedback from the campus community. This combination of advanced tools and shared knowledge can guide effective solutions, such as planting trees, installing shade structures, or upgrading infrastructure to minimize heat exposure and improve campus resilience.

What are the best ways to protect at-risk groups during extreme heat events?

Protecting those most at risk during extreme heat events calls for a combination of planning, community involvement, and smart infrastructure. Early warning systems and public education play a key role in alerting people to heat dangers, recognizing signs of heat-related illnesses, and learning practical ways to stay safe. Ensuring access to cooling centers or air-conditioned spaces is crucial for safeguarding vulnerable groups, such as older adults, young children, and individuals with chronic health conditions.

Efforts that focus on the community, like identifying high-risk populations and creating targeted solutions, are equally important. Expanding urban tree canopies, adding more shaded areas, and using green infrastructure help reduce local temperatures while offering natural cooling benefits. Together, these measures create a proactive approach to protecting the most vulnerable during intense heat waves.

How can universities use green infrastructure to stay cooler and more sustainable?

Universities have a significant opportunity to address heat challenges and promote ecological health by integrating green infrastructure into their campuses. Initiatives such as planting shade trees, installing green roofs, and incorporating permeable surfaces help reduce urban heat, improve air quality, and manage stormwater more efficiently.

Creating shaded outdoor areas and expanding tree canopies further enhances campus comfort by offering cooler spaces for students, staff, and visitors. When combined with careful planning and collaboration among stakeholders, these strategies can be tailored to meet the specific needs of each campus. By embracing these nature-focused solutions, universities can foster environments that are both resilient to heat and supportive of long-term ecological balance.

Related Blog Posts

How to Build a Climate Resilience Plan for Universities & Research Institutions

How to Integrate Climate Risk into Infrastructure Planning for Universities & Research Institutions

How to Build Heat Resilience & Urban Greening for Municipalities & Government Agencies

How to Build Heat Resilience & Urban Greening for Corporations

FAQ

01

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

02

What makes Council Fire different?

03

Who does Council Fire you work with?

04

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

05

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

06

How does Council Fire define and measure success?

Feb 1, 2026

How to Build Heat Resilience & Urban Greening for Universities & Research Institutions

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Actionable guidance for universities to map heat risks, expand urban greening, set up cooling centers, protect vulnerable groups, and monitor outcomes.

How to Build Heat Resilience & Urban Greening for Universities & Research Institutions

Universities face rising temperatures and urban heat islands that disrupt campus life, strain infrastructure, and endanger public health. Extreme heat impacts outdoor workers, student athletes, and infrastructure like dorms and labs. Projections indicate heat waves will intensify, with Boston seeing triple the 90°F days by 2044 compared to past decades.

To address these challenges, universities are adopting strategies such as:

Mapping Heat Risks: Using sensors for localized data to identify hotspots and vulnerable populations.

Green Infrastructure: Planting trees, installing green roofs, and using vegetation to cool campuses.

Energy Upgrades: Adding cool roofs, reflective pavements, and renewable energy systems to reduce heat absorption.

Cooling Centers: Preparing air-conditioned spaces for heat waves, with backup power and accessible resources.

Worker Safety: Providing hydration stations, shaded areas, and heat safety training for outdoor staff.

Collaborative Planning: Engaging students, staff, and local communities to prioritize solutions.

Long-term efforts include climate-adaptive landscaping, sustainable transportation systems, and continuous monitoring to refine strategies over time. These measures not only protect campus communities but also serve as models for broader urban resilience.

University Heat Resilience Implementation Framework: Assessment to Action

Building Urban Resilience – Session 3 from the Urban & Heat Learning Journey

How to Assess Campus Heat Vulnerability and Climate Risks

To effectively implement strategies for resilience, campuses must first conduct detailed mapping of extreme heat. This requires hyperlocal data that captures the unique microclimates created by buildings, pavement, and vegetation. Such assessments form the foundation for precise and impactful heat resilience measures.

How to Identify Heat-Prone Areas and Climate Hazards

Utilizing a combination of stationary and mobile sensors is key to gathering high-frequency, localized temperature data. In July 2024, MIT deployed sensors across its campus and on recycling trucks, uncovering that certain areas consistently recorded temperatures over 100°F - significantly higher than readings from regional weather stations[3].

Graduate student Sanjana Paul explained:

"Urban environmental phenomena are hyperlocal. While National Weather Service readouts at locations like Logan Airport are extremely valuable, this gives us a detailed understanding of campus microclimates."[3]

To expand sensor networks affordably, universities can involve engineering students in designing and building custom sensors. For example, MIT's "Engineering for Impact" course enabled students to create specialized heat sensors, which not only enhanced data collection but also provided hands-on educational opportunities. The collected data is then integrated into a Climate Resiliency Dashboard, offering a clear visualization of building-level impacts and helping planners identify high-priority areas.

Laura Tenny, Senior Campus Planner at MIT, highlighted the challenges of mapping heat:

"Heat also doesn't conform to topography like flooding, making it harder to map it with localized specificity. Microclimates, humidity levels, shade or sun aspect, and other factors contribute to heat risk."[3]

To reliably identify hotspots, institutions should gather data over three to four summers. For instance, in July 2023, the University of Texas at Arlington hosted design charrettes where faculty, students, and staff collaborated to locate heat-prone areas and create a prioritization matrix. This matrix incorporated watershed locations alongside ecological and community factors[6].

How to Evaluate Vulnerable Populations and Infrastructure

Mapping heat-prone areas is just one step; universities also need to assess who and what is most vulnerable. Brian Goldberg, Assistant Director of MIT's Office of Sustainability, emphasized:

"While stress on campus infrastructure is one factor we are evaluating, our primary focus is the vulnerability of people to extreme heat."[3]

To identify at-risk groups, universities should focus on roles with high heat exposure - such as maintenance crews, kitchen staff, and student athletes. This evaluation can be guided by four factors: social and environmental conditions, isolation, access to air conditioning, and the prevalence of chronic health conditions[8].

Susy Jones, Senior Sustainability Project Manager at MIT, reflected on the equity aspects of heat vulnerability:

"We know that people on our campus are already experiencing these extreme heat days differently. We need to design strategies and augment existing interventions with equity in mind."[3]

In addition to human vulnerability, institutions must assess critical infrastructure such as dormitories and research laboratories. Effective temperature control in these spaces is vital for safety and operational continuity. A thorough evaluation should consider five dimensions: Ecosystem Services, Infrastructure, Social Equity and Governance, Health and Wellness, and Economic factors[7].

How to Document Baseline Conditions

Establishing baseline conditions requires combining sensor data with community surveys to capture the lived experiences of heat impacts.

Universities should centralize this information on digital platforms for better organization and analysis. For example, MIT's Climate Resiliency Dashboard integrates heat risk data with other climate hazards, such as flooding, offering planners a comprehensive view of vulnerabilities. These dashboards must remain adaptable, evolving as new data becomes available, to ensure resilience mapping is an ongoing process[7].

Baseline documentation also involves evaluating the institution's current adaptive capacity - the ability to adjust to climate challenges and reduce potential damages. By collecting both environmental data and community feedback over multiple years, universities can create a solid foundation for effective, targeted heat resilience strategies.

Heat Mitigation Strategies for University Campuses

When universities assess their heat vulnerabilities, they can take specific steps to lower temperatures and improve comfort across campus. These efforts typically fall into three main areas: improving the built environment, introducing green infrastructure, and refining energy systems.

Cooling the Built Environment

One of the most effective ways to address heat at the building level is through cool roofs. These roofs use materials that reflect sunlight and release heat more effectively than traditional roofing, reducing heat buildup.

In addition to roofs, universities can adopt cool pavements for parking lots and pedestrian pathways. Materials designed to reflect sunlight or allow water to pass through can significantly cut down on heat absorption in these frequently used spaces. Adding architectural shading, such as covered walkways, awnings, or extended building overhangs, also improves outdoor comfort by providing relief from direct sunlight.

Incorporating these updates into routine capital improvement projects ensures that heat mitigation becomes a long-term commitment rather than a series of standalone fixes. Pairing these structural upgrades with natural cooling methods further amplifies their impact.

Green Infrastructure Solutions

Tree canopies offer immediate relief by shading surfaces and cooling the surrounding air through evapotranspiration. Planting drought-resistant, dense-canopy trees along busy walkways and near building entrances can maximize their cooling effects. However, careful planning is essential to ensure tree roots don’t interfere with nearby rain gardens or bioswales.

Another effective strategy is green roofs, which cool buildings by reducing rooftop temperatures through evapotranspiration. Studies show that green roofs can lower rooftop temperatures by as much as 31°F compared to conventional roofs[9]. Universities often offset the costs of these installations by tapping into local rebate programs, like the District of Columbia's RiverSmart Rooftops program or Philadelphia's Green Roof Tax Credit Program[1].

For campuses with limited ground space, vertical greenery systems (like green walls) and blue-green infrastructure - which combines water features with vegetation - can provide cooling benefits. By creating green corridors that align with local wind patterns, universities can enhance airflow and redistribute heat, potentially lowering temperatures by up to 7°F[9].

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Systems

Reducing heat starts with cutting energy use. Universities can install decentralized renewable energy systems, such as rooftop solar panels, which not only generate clean energy but also shade buildings and reduce heat absorption. Heat pumps are another option, offering efficient heating and cooling while producing less waste heat than traditional HVAC systems[1].

UC Davis serves as an example of integrating energy-efficient practices with climate adaptation. Their 70-year "Living Landscape Adaptation Plan" merges horticultural science with sustainable infrastructure to prepare the campus for future climate challenges. As UC Davis Campus Planning explains:

"The UC Davis campus can become a demonstration project integrating good science, community building and teamwork that will become a model for universities and institutions facing the same threats."[4]

Universities also act as testing grounds for broader solutions. In March 2023, sustainability leaders from colleges across all 50 states, including MIT’s Julie Newman, gathered to explore ways campus-scale climate initiatives could inspire changes in surrounding communities[5]. This collaborative approach not only benefits individual campuses but also supports regional efforts to tackle climate challenges.

How to Protect People from Extreme Heat

While long-term infrastructure upgrades can help reduce campus temperatures, universities must also be ready with immediate strategies to safeguard people during heat waves. Extreme heat is the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the United States, making it critical for campuses to act swiftly and effectively during such events[11]. These measures build on earlier discussions of heat resilience and vulnerability assessments, ensuring that campuses are equipped to protect their communities when temperatures soar.

How to Establish Cooling Centers

Cooling centers provide a vital refuge during heat waves. Universities should identify and prepare campus buildings, such as libraries, student centers, or recreation facilities, that already have air conditioning and extended hours. To ensure these spaces remain functional even during power outages, they should be equipped with backup energy systems or microgrids[11].

Location is a key factor in the success of cooling centers. For example, in July 2023, the University of Texas at Arlington collaborated with the US EPA to create a prioritization matrix, helping determine where cooling interventions would best serve populations based on heat exposure and community needs[6]. Research in Los Angeles County revealed that while only 20% of people used official cooling centers during heat events, 90% sought informal options like shopping malls[10]. Universities can adapt by extending hours at campus pools and other air-conditioned areas to meet these preferences.

Cooling centers should offer more than just a cool environment. They need to provide shade, drinking water, restrooms, and clear multilingual signage. Groups most at risk include those without air conditioning at home, outdoor workers, individuals with chronic health conditions, and people living alone[10][11]. Additionally, formerly redlined neighborhoods often experience temperatures up to 7.5°F hotter during the day and 3.6°F hotter at night compared to other areas, highlighting the need for targeted support in these communities[11].

These efforts lay the groundwork for addressing the needs of vulnerable groups, including outdoor workers, as explored in the next section.

Outdoor Worker Protection and Heat Safety Protocols

Certain campus groups, such as maintenance crews, groundskeepers, kitchen staff, and student-athletes, face heightened risks due to prolonged outdoor activity in the heat. To protect these workers, universities should implement measures like hydration stations across campus, mandatory water breaks during peak heat hours, and shaded workspaces, which can include temporary canopies or permanent structures.