Dec 19, 2025

Dec 19, 2025

Frameworks for Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

Sustainability Strategy

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Explores MSPs, governance models, and co-design methods for inclusive, scalable multi-stakeholder collaboration—trade-offs, conflict resolution, and integration strategies.

Frameworks for Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

In addressing complex sustainability challenges like climate adaptation, resource management, and infrastructure resilience, collaboration among diverse stakeholders is essential. This article explores three key frameworks that facilitate such partnerships:

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs): These platforms bring together varied groups for structured dialogue, using participatory tools to align efforts and address shared concerns. MSPs emphasize broad representation, conflict management, and scalability but require significant resources and skilled facilitation.

Collaboration Governance Models: These models formalize decision-making, balancing inclusivity and efficiency. They ensure clear roles and conflict-resolution protocols, making them suitable for scaling across sectors, though they can be complex to implement.

Co-Design Frameworks: By involving stakeholders directly in solution development, co-design ensures that lived experiences shape outcomes. This approach fosters shared ownership and addresses power imbalances but demands time, resources, and skilled facilitation.

Each framework has its strengths and trade-offs. MSPs excel in coordination, governance models bring structure, and co-design focuses on tailored solutions. The best results often come from integrating elements of all three, aligning efforts with clear goals and shared accountability.

Multi-Stakeholder Collaboratives - Better Practices for Facilitation and Coordination

1. Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs)

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) bring together a range of stakeholders to tackle sustainability challenges through structured dialogue and collaborative problem-solving. These platforms follow a phased approach - exploration, divergence, co-creation, convergence, and commitment - using various participatory tools to guide discussions and decisions [2].

Inclusiveness

MSPs aim to include diverse voices, particularly those often overlooked or lacking traditional influence. By identifying "hidden" stakeholders, these platforms ensure broader representation. For example, eight landscape-level MSPs across multiple countries have improved stakeholder interactions. In India, block-level MSPs connected villages with government agencies, NGOs, and private sector players to share knowledge on agriculture and resource management [3]. Similarly, initiatives like the Partnership for Global LGBTQI+ Equality highlight how direct engagement of multiple stakeholders fosters more democratic decision-making [5].

"True inclusiveness in multi-stakeholder platforms requires moving from 'giving a seat at the table' to 'sharing the power to set the menu.'" - Council Fire [1]

To level the playing field, effective MSPs often employ neutral third-party facilitators and provide resources like financial stipends, technical support, or translation services to under-resourced groups. Platforms with inclusive governance models are 2.5 times more likely to achieve lasting policy outcomes compared to efforts led by a single sector [1]. However, building trust and fostering inclusivity often require significant upfront time and resources, particularly during the early stages.

Conflict Resolution

Disagreements are inevitable in MSPs, but they are managed through tools like Conflict Styles assessments, Ritual Dissent, and participatory learning events. These methods help stakeholders co-create solutions, prioritize actions, and commit to shared goals. MSPs are especially effective in addressing governance gaps by coordinating efforts across traditionally siloed sectors. For instance, in Oromia, Ethiopia, an MSP aligned NGO activities in rangelands, while in India, block-level platforms revived intercommunity cooperation through conservation planning [3].

Rather than focusing on positions, MSPs emphasize interest-based negotiation, uncovering solutions that address stakeholders' core needs. Joint fact-finding processes also play a crucial role, as stakeholders collectively select experts and define research parameters, creating a shared data foundation and avoiding "expert battles." Around 70% of successful MSPs cite the presence of a neutral backbone organization as essential for maintaining trust among participants [1].

Scalability

MSPs can expand their impact by linking platforms across different levels - such as villages, subdistricts, and beyond - facilitating mutual learning and influencing broader policies. In India, for example, village-level platforms evolved into block-level collaborations, enabling intervillage conservation plans and larger landscape-focused outcomes [3]. This nested governance structure allows MSPs to address large-scale issues while staying connected to local needs.

However, scalability often leads to "coordination fatigue", as the growing number of participants demands more time and resources for consensus-building. Digital tools and phased pilot projects can help MSPs scale effectively while managing these challenges.

Implementation Complexity

Designing and managing MSPs involves navigating distinct phases and employing tailored facilitation tools. For instance, NetMapping and SWOT Analysis support the exploration phase, while Open Space and Visioning techniques aid co-creation [2]. Frameworks like the Cynefin Framework for context analysis and formal Partnership Agreements help reduce complexity.

Power imbalances often complicate MSP operations, making strong facilitation and early governance charters essential. These charters clarify roles and establish conflict-resolution protocols. Additionally, the differing operational rhythms of government, private, and nonprofit sectors - each with its own timelines and success metrics - can hinder unified implementation. Long-term, flexible funding and a dedicated administrative body remain critical but challenging to secure.

MSPs promote inclusive dialogue, resolve conflicts through shared interests, and offer scalable solutions. While their complexity can be daunting, they lay the groundwork for governance models with structured decision-making frameworks, as explored in the following section.

2. Collaboration Governance Models

Collaboration governance models formalize decision-making within multi-stakeholder platforms, ensuring that all voices are heard while maintaining structure. These models can be company-led, involving direct stakeholder participation or advisory councils, or they can be multi-stakeholder, with either direct or representative participation [5].

Inclusiveness

The degree of inclusiveness hinges on whether decision-making is company-led or multi-stakeholder. In multi-stakeholder models with direct participation, like The Partnership for Global LGBTQI+ Equality, all involved parties - companies, NGOs, and governments - have formal decision-making authority to represent their interests directly [5]. Advisory models, in contrast, allow stakeholders to provide input while the company retains ultimate decision-making power.

To balance inclusiveness with efficiency, effective models use transparent representation criteria. Tools such as the Power-Interest Grid and tiered governance structures help ensure fair representation [5][6][3].

"Effective governance in multi-stakeholder environments is about creating a 'container' where conflict can be productive rather than destructive." - Council Fire [1]

Inclusiveness often requires dedicated resources. For instance, Collective Impact initiatives typically allocate 5%–15% of their total budget to governance functions, providing the administrative and technical support smaller organizations need to participate equitably. Some models even offer participation offsets, such as stipends for community members or technical assistance for smaller NGOs, to lower barriers to entry.

Once representation is established, formal conflict-resolution mechanisms are critical to sustaining collective progress.

Conflict Resolution

Formal conflict-resolution mechanisms, including conflict-style assessments, adaptive dialogue, and structured escalation processes, help shift focus from individual positions to shared interests, encouraging creative, consensus-driven solutions [2][3][9]. In company-led models, conflicts are often handled internally with minimal external involvement. Multi-stakeholder models, however, require structured negotiations among all decision-makers.

Platforms with written conflict-resolution protocols are 40% more likely to achieve long-term success than those relying on informal agreements [3]. A notable example is the Oromia MSP in Ethiopia, which addressed governance gaps by coordinating NGO activities across sectors with transparent conflict-management processes. Consent-based decision-making - where proposals move forward unless there are "paramount objections" - offers a balanced approach between full consensus and majority rule.

Scalability

Multi-stakeholder models with representative participation are well-suited for scaling by linking governance across different levels. In India, for instance, village-level platforms have evolved into block-level collaborations, enabling coordination across villages for broader conservation and landscape management through clear communication channels [3]. This nested governance structure allows local groups to contribute to regional or national steering bodies.

Company-led models, on the other hand, often face challenges in scaling beyond corporate networks due to their narrower stakeholder engagement. As collaborations expand, decision-making tends to shift from direct participation to representative systems, where stakeholder categories elect spokespeople to streamline coordination.

Tying scalability to established institutions, such as municipal councils or river-basin authorities, enhances legitimacy and reduces redundancy [3][7][8]. Digital governance tools, like asynchronous decision-making platforms, are also increasingly used to address time zone and resource challenges.

Implementation Complexity

Multi-stakeholder models demand skilled facilitation, clear processes, and written agreements to manage the diverse priorities of participating organizations. Allocating budgets for facilitation and monitoring can reduce friction and improve clarity [2][1]. For example, BSR's framework helped one partner group transition to a multi-stakeholder representative model by balancing democratic decision-making with manageable complexity [5].

"Governance is not just about who makes the decisions, but how the information flows to those decisions to ensure no stakeholder is left in the dark." - Council Fire [1]

The success of implementation depends on aligning the governance structure with the issue at hand. High-stakes or politically sensitive challenges often necessitate robust, inclusive governance, even if it slows decision-making. Conversely, technical issues with narrower scopes may benefit from lighter structures. Written agreements outlining mandates, roles, decision rules, and review cycles can help reduce ambiguity, while dedicated budgets address recurring costs - an area many collaborations underestimate. A survey of over 100 global partnerships revealed that 65% of participants identified unclear governance as the main reason for stakeholder withdrawal [1].

This structured approach to decision-making sets the stage for the co-design frameworks that follow, where stakeholders work together to develop solutions.

3. Co-Design Frameworks

Co-design frameworks redefine the role of stakeholders, turning them into active collaborators who help identify problems and craft solutions throughout the project lifecycle. Instead of experts designing for communities or organizations, this approach values lived experiences as much as technical expertise, ensuring that those most impacted by a challenge play a central role in shaping the response. Using the Double Diamond process - discovery, definition, development, and delivery - co-design integrates stakeholders directly into the solution-building process, complementing multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSPs) and governance models.

Inclusiveness

One of the strengths of co-design lies in its ability to address power imbalances intentionally. A 2022 UK study highlighted this, showing how the involvement of 50 diverse stakeholders resulted in a well-validated whole-school physical activity framework [4]. Successful co-design begins with power mapping to identify decision-makers and marginalized groups, followed by deliberate efforts to amplify underrepresented voices. Strategies include equitable compensation, plain-language communication, and accessible meeting formats.

"To create lasting change, we must move from designing for people to designing with them." - Council Fire [1]

Economic barriers must also be addressed. Providing compensation, childcare stipends, transportation support, and flexible meeting times can make participation more accessible. When participants see how their input shapes the design through iterative feedback loops, trust grows, and long-term engagement becomes achievable. With inclusiveness secured, co-design can transform potential conflicts into opportunities for creative problem-solving.

Conflict Resolution

Co-design reframes conflicts by focusing on ideas rather than individuals, using tools like rapid prototyping. The Double Diamond’s structured phases of divergence and convergence allow stakeholders to express disagreements, challenge assumptions, and explore trade-offs in a safe environment. For instance, in the UK whole-school framework project, multiple rounds of divergent brainstorming followed by convergent refinement enabled participants to overcome differences and co-create a solution no single group could have developed alone [4].

Interest-based negotiation is a key element here. Facilitators guide participants to explore why they want something, uncovering shared interests that lead to creative compromises. Neutral facilitation ensures that discussions remain productive and that no single voice dominates. Organizations like Council Fire support this process by combining tools such as joint fact-finding, multi-criteria decision analysis, and structured dialogue to help stakeholders reconcile competing environmental, social, and financial goals.

Scalability

Co-design frameworks can scale effectively when built on flexible processes and cross-scale learning rather than rigid templates. For example, the whole-school physical activity framework used a six-phase Double Diamond approach, maintaining core stages - discover, define, develop, deliver - while allowing local stakeholders to adapt activities and priorities to their specific needs [4]. Research shows that linking local co-design efforts across scales, from community to state levels, can influence broader policy and investment decisions while retaining local relevance.

As projects grow, scalability often requires shifting from intensive direct participation, like full-stakeholder workshops, to representative participation or digital collaboration platforms. Standardized toolkits, facilitation guides, and shared metrics can help regional or local teams replicate the process while maintaining feedback loops to share lessons learned. However, this modular approach must account for context-specific factors like regulatory requirements, local governance norms, and sector-specific challenges, such as U.S. public notice rules or tribal sovereignty considerations.

While scalability offers opportunities, it also introduces complexities that require careful coordination.

Implementation Complexity

Co-design processes demand significant time, resources, and skilled facilitation. For instance, the UK whole-school framework required six distinct phases involving 50 participants across workshops, online revisions, and iterative voting cycles - a timeline spanning months, not weeks [4]. Costs include professional facilitation, outreach, venue logistics, materials, data collection, and participant compensation. While these expenses may exceed those of traditional top-down planning, they can help prevent costly implementation failures later.

Skilled facilitators are essential to manage group dynamics, resolve conflicts, and address power imbalances. Aligning multiple organizations’ legal and accountability structures adds further complexity, especially when public agencies and private firms must integrate co-designed outcomes into official plans and budgets. Organizations can navigate these challenges by defining clear phases, allocating multi-year budgets, partnering with experienced intermediaries - like universities, consultancies such as Council Fire, or NGOs - and testing frameworks through phased pilots before scaling up. Despite these hurdles, co-design turns top-down interventions into collaborative solutions, revealing system-wide connections and paving the way for meaningful change.

Advantages and Disadvantages

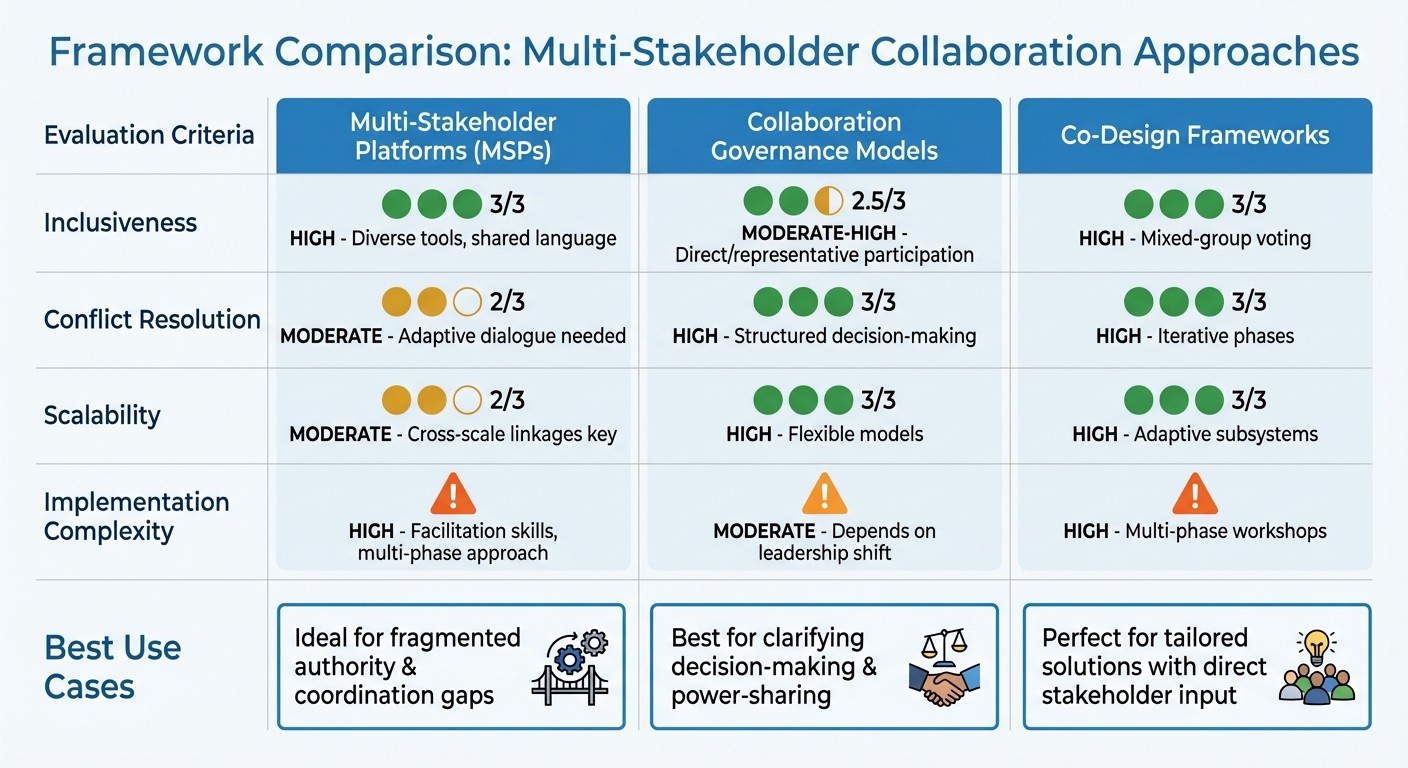

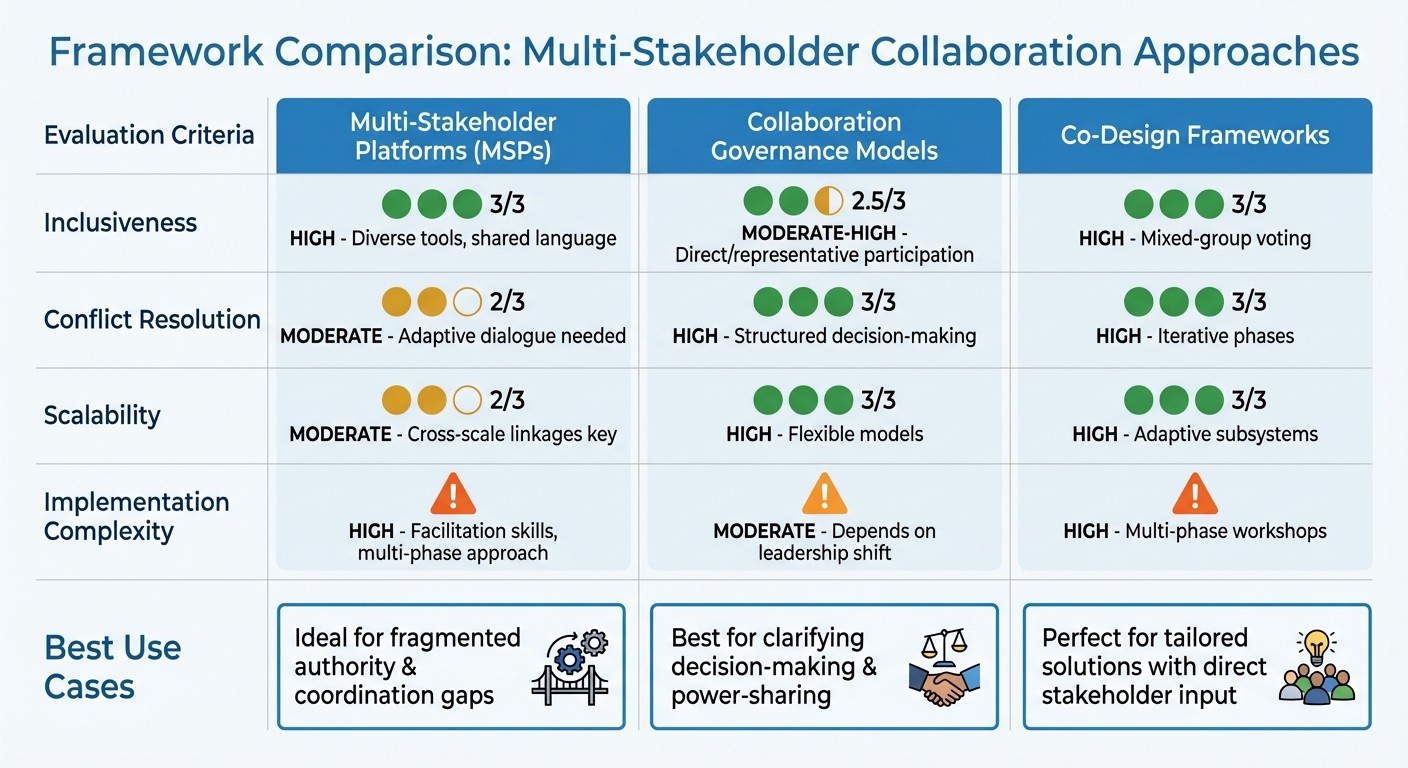

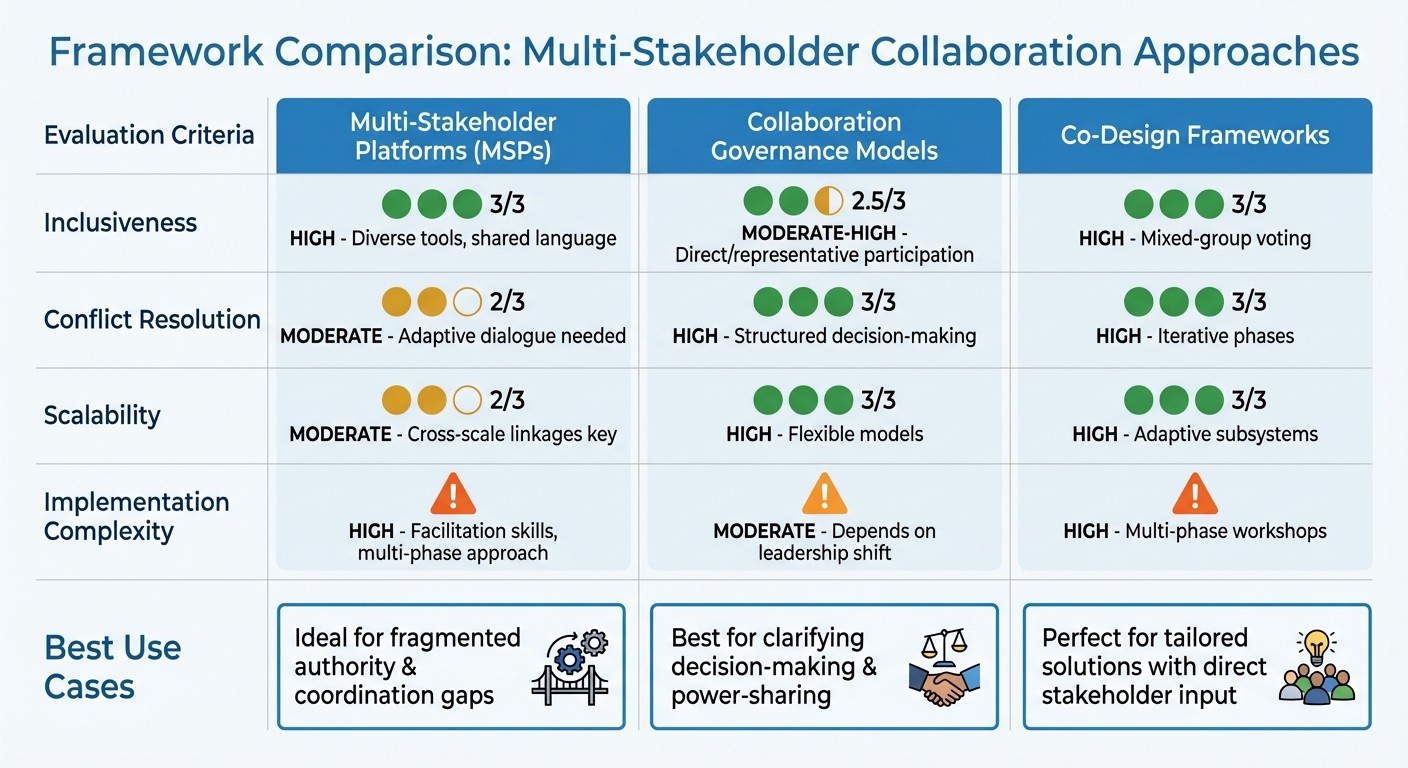

Comparison of Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration Frameworks: Strengths and Trade-offs

This section provides a concise overview of the key strengths and limitations of the frameworks discussed earlier, helping organizations weigh their options and make informed decisions based on their unique goals and circumstances.

Each framework brings its own set of benefits and challenges, offering different approaches to tackling complex issues. By understanding these trade-offs, organizations can better align their strategies with their specific needs.

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) are known for their inclusiveness, as they bring together a wide range of participants from government, businesses, and civil society to address multifaceted problems. A study of eight MSPs across seven countries revealed positive results in fostering inclusion, collaboration, and trust-building [3]. However, they come with high implementation complexity, requiring skilled facilitation and a phased approach [2]. Their scalability depends on forming effective cross-scale linkages [3]. While they encourage dialogue and trust, conflict resolution tends to be moderate, as these processes take time [3].

Collaboration Governance Models shine in conflict resolution, thanks to structured decision-making processes that clearly define roles and protocols [5]. These models also offer high scalability, as their flexible structures can expand across various sectors [5]. Their inclusiveness varies from moderate to high, depending on whether they rely on direct participation or representative committees [5]. The primary challenge is moderate implementation complexity, especially when transitioning from corporate-led to multi-stakeholder governance, which requires balancing control between companies and stakeholders [5].

Co-Design Frameworks excel in both inclusiveness and conflict resolution. For example, a UK initiative involving 50 stakeholders - ranging from headteachers to researchers - developed a whole-school physical activity framework through mixed-group workshops and iterative voting [4]. This process demonstrated the effectiveness of collaborative refinement, with one draft receiving the highest votes across nine stakeholder groups [4]. These frameworks also support scalability by using adaptive subsystems and driving systemic change [4]. However, they involve high implementation complexity, requiring iterative, multi-phase workshops [4].

Framework | Inclusiveness | Conflict Resolution | Scalability | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms | Moderate (adaptive dialogue needed) [3] | Moderate (cross-scale linkages key) [3] | High (facilitation skills, multi-phase approach) [2] | |

Collaboration Governance Models | Moderate-High (direct/representative participation) [5] | High (structured decision-making) [5] | High (flexible models) [5] | Moderate (depends on leadership shift) [5] |

Co-Design Frameworks | High (mixed-group voting) [4] | High (iterative phases) [4] | High (adaptive subsystems) [4] | High (multi-phase workshops) [4] |

Conclusion

When tackling challenges in multi-stakeholder collaboration, choosing the right framework is essential for success. The choice should be guided by the specific issue at hand. For example, Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) are ideal when the main challenge lies in fragmented authority or coordination gaps. Collaboration Governance Models excel when decision-making processes and power-sharing need clarity, particularly in business-led sustainability initiatives or public-private partnerships. Meanwhile, Co-Design Frameworks work best for creating tailored solutions with direct input from the individuals or groups who will use them.

Each framework offers distinct strengths and trade-offs. MSPs foster dialogue in previously disconnected spaces but often progress slowly. Governance models bring structure and scalability but can lead to power imbalances if not carefully constructed. Co-design, while rooted in lived experiences and fostering shared ownership, demands significant time and resources. Despite these differences, all three frameworks aim to streamline decision-making, promote collaborative ownership, and deliver measurable environmental and social benefits.

To make the best choice, organizations should ask three key questions: What’s the primary challenge - coordination, governance, or solution design? What’s the biggest risk - legitimacy, feasibility, or quality? And, what resources - budget and time - are available? Often, the most effective approach combines elements of all three frameworks: MSPs to create a platform for dialogue, governance models to define roles and responsibilities, and co-design methods for focused, actionable solutions.

Council Fire exemplifies how these frameworks can work together. Their systems-thinking approach identifies intersecting stakeholder interests, resolves conflicts early, and establishes clear engagement rules to prevent power imbalances. They also design governance structures that align multi-stakeholder efforts with ESG goals, ensuring that collaboration leads to measurable environmental and social outcomes rather than just discussions.

Ultimately, the most impactful collaborations don’t rely on a single framework. Instead, they adapt and integrate approaches as challenges evolve. By blending MSPs, governance models, and co-design methods, organizations can bridge coordination gaps, address power dynamics, and deliver community-centered solutions. Whether working across jurisdictions, forming business coalitions, or co-creating with local communities, success hinges on intentional design that prioritizes inclusion, adaptive learning, and shared accountability from the outset.

FAQs

How do Multi-Stakeholder Platforms resolve conflicts among participants with differing perspectives?

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) play a critical role in resolving conflicts by promoting open dialogue, encouraging transparency, and working toward shared objectives. They provide an inclusive environment where every participant has the opportunity to contribute, fostering mutual understanding and building trust among diverse stakeholders.

When disagreements arise, MSPs rely on collaborative problem-solving strategies. These may include addressing power imbalances, facilitating mediation, and focusing on solutions that reflect the collective interests of the group. This approach ensures decisions are equitable, widely supported, and geared toward achieving lasting cooperation and consensus.

What are the key challenges in implementing collaboration governance models?

Implementing governance models for collaboration often comes with its own set of challenges. One major hurdle is finding ways to balance the varied interests of stakeholders while addressing uneven power dynamics that might arise. Without careful attention, these issues can lead to friction or misunderstandings.

Another critical element is defining clear roles and responsibilities for all participants. Ambiguity in this area can lead to confusion and inefficiencies, making it harder for the group to function effectively.

Equally important is maintaining open communication channels and building trust and commitment among all parties over time. These aspects require consistent effort and thoughtful planning to ensure the collaboration stays productive and fair for everyone involved.

How do Co-Design Frameworks promote inclusivity and address power dynamics?

Co-Design Frameworks are all about bringing people together and making sure everyone has a say in the decision-making process. They provide a platform where individuals from different backgrounds, experiences, and levels of influence can actively participate and share their insights.

By focusing on openness and shared responsibility, these frameworks help establish trust and give a louder voice to those who might otherwise be overlooked or marginalized. This method ensures that the final outcomes incorporate a variety of viewpoints and address the needs of the whole group, balancing power dynamics and encouraging fair participation.

Related Blog Posts

Latest Articles

©2025

FAQ

FAQ

01

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

02

What makes Council Fire different?

03

Who does Council Fire you work with?

04

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

05

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

06

How does Council Fire define and measure success?

01

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

02

What makes Council Fire different?

03

Who does Council Fire you work with?

04

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

05

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

06

How does Council Fire define and measure success?

Dec 19, 2025

Frameworks for Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Explores MSPs, governance models, and co-design methods for inclusive, scalable multi-stakeholder collaboration—trade-offs, conflict resolution, and integration strategies.

Frameworks for Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

In addressing complex sustainability challenges like climate adaptation, resource management, and infrastructure resilience, collaboration among diverse stakeholders is essential. This article explores three key frameworks that facilitate such partnerships:

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs): These platforms bring together varied groups for structured dialogue, using participatory tools to align efforts and address shared concerns. MSPs emphasize broad representation, conflict management, and scalability but require significant resources and skilled facilitation.

Collaboration Governance Models: These models formalize decision-making, balancing inclusivity and efficiency. They ensure clear roles and conflict-resolution protocols, making them suitable for scaling across sectors, though they can be complex to implement.

Co-Design Frameworks: By involving stakeholders directly in solution development, co-design ensures that lived experiences shape outcomes. This approach fosters shared ownership and addresses power imbalances but demands time, resources, and skilled facilitation.

Each framework has its strengths and trade-offs. MSPs excel in coordination, governance models bring structure, and co-design focuses on tailored solutions. The best results often come from integrating elements of all three, aligning efforts with clear goals and shared accountability.

Multi-Stakeholder Collaboratives - Better Practices for Facilitation and Coordination

1. Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs)

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) bring together a range of stakeholders to tackle sustainability challenges through structured dialogue and collaborative problem-solving. These platforms follow a phased approach - exploration, divergence, co-creation, convergence, and commitment - using various participatory tools to guide discussions and decisions [2].

Inclusiveness

MSPs aim to include diverse voices, particularly those often overlooked or lacking traditional influence. By identifying "hidden" stakeholders, these platforms ensure broader representation. For example, eight landscape-level MSPs across multiple countries have improved stakeholder interactions. In India, block-level MSPs connected villages with government agencies, NGOs, and private sector players to share knowledge on agriculture and resource management [3]. Similarly, initiatives like the Partnership for Global LGBTQI+ Equality highlight how direct engagement of multiple stakeholders fosters more democratic decision-making [5].

"True inclusiveness in multi-stakeholder platforms requires moving from 'giving a seat at the table' to 'sharing the power to set the menu.'" - Council Fire [1]

To level the playing field, effective MSPs often employ neutral third-party facilitators and provide resources like financial stipends, technical support, or translation services to under-resourced groups. Platforms with inclusive governance models are 2.5 times more likely to achieve lasting policy outcomes compared to efforts led by a single sector [1]. However, building trust and fostering inclusivity often require significant upfront time and resources, particularly during the early stages.

Conflict Resolution

Disagreements are inevitable in MSPs, but they are managed through tools like Conflict Styles assessments, Ritual Dissent, and participatory learning events. These methods help stakeholders co-create solutions, prioritize actions, and commit to shared goals. MSPs are especially effective in addressing governance gaps by coordinating efforts across traditionally siloed sectors. For instance, in Oromia, Ethiopia, an MSP aligned NGO activities in rangelands, while in India, block-level platforms revived intercommunity cooperation through conservation planning [3].

Rather than focusing on positions, MSPs emphasize interest-based negotiation, uncovering solutions that address stakeholders' core needs. Joint fact-finding processes also play a crucial role, as stakeholders collectively select experts and define research parameters, creating a shared data foundation and avoiding "expert battles." Around 70% of successful MSPs cite the presence of a neutral backbone organization as essential for maintaining trust among participants [1].

Scalability

MSPs can expand their impact by linking platforms across different levels - such as villages, subdistricts, and beyond - facilitating mutual learning and influencing broader policies. In India, for example, village-level platforms evolved into block-level collaborations, enabling intervillage conservation plans and larger landscape-focused outcomes [3]. This nested governance structure allows MSPs to address large-scale issues while staying connected to local needs.

However, scalability often leads to "coordination fatigue", as the growing number of participants demands more time and resources for consensus-building. Digital tools and phased pilot projects can help MSPs scale effectively while managing these challenges.

Implementation Complexity

Designing and managing MSPs involves navigating distinct phases and employing tailored facilitation tools. For instance, NetMapping and SWOT Analysis support the exploration phase, while Open Space and Visioning techniques aid co-creation [2]. Frameworks like the Cynefin Framework for context analysis and formal Partnership Agreements help reduce complexity.

Power imbalances often complicate MSP operations, making strong facilitation and early governance charters essential. These charters clarify roles and establish conflict-resolution protocols. Additionally, the differing operational rhythms of government, private, and nonprofit sectors - each with its own timelines and success metrics - can hinder unified implementation. Long-term, flexible funding and a dedicated administrative body remain critical but challenging to secure.

MSPs promote inclusive dialogue, resolve conflicts through shared interests, and offer scalable solutions. While their complexity can be daunting, they lay the groundwork for governance models with structured decision-making frameworks, as explored in the following section.

2. Collaboration Governance Models

Collaboration governance models formalize decision-making within multi-stakeholder platforms, ensuring that all voices are heard while maintaining structure. These models can be company-led, involving direct stakeholder participation or advisory councils, or they can be multi-stakeholder, with either direct or representative participation [5].

Inclusiveness

The degree of inclusiveness hinges on whether decision-making is company-led or multi-stakeholder. In multi-stakeholder models with direct participation, like The Partnership for Global LGBTQI+ Equality, all involved parties - companies, NGOs, and governments - have formal decision-making authority to represent their interests directly [5]. Advisory models, in contrast, allow stakeholders to provide input while the company retains ultimate decision-making power.

To balance inclusiveness with efficiency, effective models use transparent representation criteria. Tools such as the Power-Interest Grid and tiered governance structures help ensure fair representation [5][6][3].

"Effective governance in multi-stakeholder environments is about creating a 'container' where conflict can be productive rather than destructive." - Council Fire [1]

Inclusiveness often requires dedicated resources. For instance, Collective Impact initiatives typically allocate 5%–15% of their total budget to governance functions, providing the administrative and technical support smaller organizations need to participate equitably. Some models even offer participation offsets, such as stipends for community members or technical assistance for smaller NGOs, to lower barriers to entry.

Once representation is established, formal conflict-resolution mechanisms are critical to sustaining collective progress.

Conflict Resolution

Formal conflict-resolution mechanisms, including conflict-style assessments, adaptive dialogue, and structured escalation processes, help shift focus from individual positions to shared interests, encouraging creative, consensus-driven solutions [2][3][9]. In company-led models, conflicts are often handled internally with minimal external involvement. Multi-stakeholder models, however, require structured negotiations among all decision-makers.

Platforms with written conflict-resolution protocols are 40% more likely to achieve long-term success than those relying on informal agreements [3]. A notable example is the Oromia MSP in Ethiopia, which addressed governance gaps by coordinating NGO activities across sectors with transparent conflict-management processes. Consent-based decision-making - where proposals move forward unless there are "paramount objections" - offers a balanced approach between full consensus and majority rule.

Scalability

Multi-stakeholder models with representative participation are well-suited for scaling by linking governance across different levels. In India, for instance, village-level platforms have evolved into block-level collaborations, enabling coordination across villages for broader conservation and landscape management through clear communication channels [3]. This nested governance structure allows local groups to contribute to regional or national steering bodies.

Company-led models, on the other hand, often face challenges in scaling beyond corporate networks due to their narrower stakeholder engagement. As collaborations expand, decision-making tends to shift from direct participation to representative systems, where stakeholder categories elect spokespeople to streamline coordination.

Tying scalability to established institutions, such as municipal councils or river-basin authorities, enhances legitimacy and reduces redundancy [3][7][8]. Digital governance tools, like asynchronous decision-making platforms, are also increasingly used to address time zone and resource challenges.

Implementation Complexity

Multi-stakeholder models demand skilled facilitation, clear processes, and written agreements to manage the diverse priorities of participating organizations. Allocating budgets for facilitation and monitoring can reduce friction and improve clarity [2][1]. For example, BSR's framework helped one partner group transition to a multi-stakeholder representative model by balancing democratic decision-making with manageable complexity [5].

"Governance is not just about who makes the decisions, but how the information flows to those decisions to ensure no stakeholder is left in the dark." - Council Fire [1]

The success of implementation depends on aligning the governance structure with the issue at hand. High-stakes or politically sensitive challenges often necessitate robust, inclusive governance, even if it slows decision-making. Conversely, technical issues with narrower scopes may benefit from lighter structures. Written agreements outlining mandates, roles, decision rules, and review cycles can help reduce ambiguity, while dedicated budgets address recurring costs - an area many collaborations underestimate. A survey of over 100 global partnerships revealed that 65% of participants identified unclear governance as the main reason for stakeholder withdrawal [1].

This structured approach to decision-making sets the stage for the co-design frameworks that follow, where stakeholders work together to develop solutions.

3. Co-Design Frameworks

Co-design frameworks redefine the role of stakeholders, turning them into active collaborators who help identify problems and craft solutions throughout the project lifecycle. Instead of experts designing for communities or organizations, this approach values lived experiences as much as technical expertise, ensuring that those most impacted by a challenge play a central role in shaping the response. Using the Double Diamond process - discovery, definition, development, and delivery - co-design integrates stakeholders directly into the solution-building process, complementing multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSPs) and governance models.

Inclusiveness

One of the strengths of co-design lies in its ability to address power imbalances intentionally. A 2022 UK study highlighted this, showing how the involvement of 50 diverse stakeholders resulted in a well-validated whole-school physical activity framework [4]. Successful co-design begins with power mapping to identify decision-makers and marginalized groups, followed by deliberate efforts to amplify underrepresented voices. Strategies include equitable compensation, plain-language communication, and accessible meeting formats.

"To create lasting change, we must move from designing for people to designing with them." - Council Fire [1]

Economic barriers must also be addressed. Providing compensation, childcare stipends, transportation support, and flexible meeting times can make participation more accessible. When participants see how their input shapes the design through iterative feedback loops, trust grows, and long-term engagement becomes achievable. With inclusiveness secured, co-design can transform potential conflicts into opportunities for creative problem-solving.

Conflict Resolution

Co-design reframes conflicts by focusing on ideas rather than individuals, using tools like rapid prototyping. The Double Diamond’s structured phases of divergence and convergence allow stakeholders to express disagreements, challenge assumptions, and explore trade-offs in a safe environment. For instance, in the UK whole-school framework project, multiple rounds of divergent brainstorming followed by convergent refinement enabled participants to overcome differences and co-create a solution no single group could have developed alone [4].

Interest-based negotiation is a key element here. Facilitators guide participants to explore why they want something, uncovering shared interests that lead to creative compromises. Neutral facilitation ensures that discussions remain productive and that no single voice dominates. Organizations like Council Fire support this process by combining tools such as joint fact-finding, multi-criteria decision analysis, and structured dialogue to help stakeholders reconcile competing environmental, social, and financial goals.

Scalability

Co-design frameworks can scale effectively when built on flexible processes and cross-scale learning rather than rigid templates. For example, the whole-school physical activity framework used a six-phase Double Diamond approach, maintaining core stages - discover, define, develop, deliver - while allowing local stakeholders to adapt activities and priorities to their specific needs [4]. Research shows that linking local co-design efforts across scales, from community to state levels, can influence broader policy and investment decisions while retaining local relevance.

As projects grow, scalability often requires shifting from intensive direct participation, like full-stakeholder workshops, to representative participation or digital collaboration platforms. Standardized toolkits, facilitation guides, and shared metrics can help regional or local teams replicate the process while maintaining feedback loops to share lessons learned. However, this modular approach must account for context-specific factors like regulatory requirements, local governance norms, and sector-specific challenges, such as U.S. public notice rules or tribal sovereignty considerations.

While scalability offers opportunities, it also introduces complexities that require careful coordination.

Implementation Complexity

Co-design processes demand significant time, resources, and skilled facilitation. For instance, the UK whole-school framework required six distinct phases involving 50 participants across workshops, online revisions, and iterative voting cycles - a timeline spanning months, not weeks [4]. Costs include professional facilitation, outreach, venue logistics, materials, data collection, and participant compensation. While these expenses may exceed those of traditional top-down planning, they can help prevent costly implementation failures later.

Skilled facilitators are essential to manage group dynamics, resolve conflicts, and address power imbalances. Aligning multiple organizations’ legal and accountability structures adds further complexity, especially when public agencies and private firms must integrate co-designed outcomes into official plans and budgets. Organizations can navigate these challenges by defining clear phases, allocating multi-year budgets, partnering with experienced intermediaries - like universities, consultancies such as Council Fire, or NGOs - and testing frameworks through phased pilots before scaling up. Despite these hurdles, co-design turns top-down interventions into collaborative solutions, revealing system-wide connections and paving the way for meaningful change.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Comparison of Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration Frameworks: Strengths and Trade-offs

This section provides a concise overview of the key strengths and limitations of the frameworks discussed earlier, helping organizations weigh their options and make informed decisions based on their unique goals and circumstances.

Each framework brings its own set of benefits and challenges, offering different approaches to tackling complex issues. By understanding these trade-offs, organizations can better align their strategies with their specific needs.

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) are known for their inclusiveness, as they bring together a wide range of participants from government, businesses, and civil society to address multifaceted problems. A study of eight MSPs across seven countries revealed positive results in fostering inclusion, collaboration, and trust-building [3]. However, they come with high implementation complexity, requiring skilled facilitation and a phased approach [2]. Their scalability depends on forming effective cross-scale linkages [3]. While they encourage dialogue and trust, conflict resolution tends to be moderate, as these processes take time [3].

Collaboration Governance Models shine in conflict resolution, thanks to structured decision-making processes that clearly define roles and protocols [5]. These models also offer high scalability, as their flexible structures can expand across various sectors [5]. Their inclusiveness varies from moderate to high, depending on whether they rely on direct participation or representative committees [5]. The primary challenge is moderate implementation complexity, especially when transitioning from corporate-led to multi-stakeholder governance, which requires balancing control between companies and stakeholders [5].

Co-Design Frameworks excel in both inclusiveness and conflict resolution. For example, a UK initiative involving 50 stakeholders - ranging from headteachers to researchers - developed a whole-school physical activity framework through mixed-group workshops and iterative voting [4]. This process demonstrated the effectiveness of collaborative refinement, with one draft receiving the highest votes across nine stakeholder groups [4]. These frameworks also support scalability by using adaptive subsystems and driving systemic change [4]. However, they involve high implementation complexity, requiring iterative, multi-phase workshops [4].

Framework | Inclusiveness | Conflict Resolution | Scalability | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms | Moderate (adaptive dialogue needed) [3] | Moderate (cross-scale linkages key) [3] | High (facilitation skills, multi-phase approach) [2] | |

Collaboration Governance Models | Moderate-High (direct/representative participation) [5] | High (structured decision-making) [5] | High (flexible models) [5] | Moderate (depends on leadership shift) [5] |

Co-Design Frameworks | High (mixed-group voting) [4] | High (iterative phases) [4] | High (adaptive subsystems) [4] | High (multi-phase workshops) [4] |

Conclusion

When tackling challenges in multi-stakeholder collaboration, choosing the right framework is essential for success. The choice should be guided by the specific issue at hand. For example, Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) are ideal when the main challenge lies in fragmented authority or coordination gaps. Collaboration Governance Models excel when decision-making processes and power-sharing need clarity, particularly in business-led sustainability initiatives or public-private partnerships. Meanwhile, Co-Design Frameworks work best for creating tailored solutions with direct input from the individuals or groups who will use them.

Each framework offers distinct strengths and trade-offs. MSPs foster dialogue in previously disconnected spaces but often progress slowly. Governance models bring structure and scalability but can lead to power imbalances if not carefully constructed. Co-design, while rooted in lived experiences and fostering shared ownership, demands significant time and resources. Despite these differences, all three frameworks aim to streamline decision-making, promote collaborative ownership, and deliver measurable environmental and social benefits.

To make the best choice, organizations should ask three key questions: What’s the primary challenge - coordination, governance, or solution design? What’s the biggest risk - legitimacy, feasibility, or quality? And, what resources - budget and time - are available? Often, the most effective approach combines elements of all three frameworks: MSPs to create a platform for dialogue, governance models to define roles and responsibilities, and co-design methods for focused, actionable solutions.

Council Fire exemplifies how these frameworks can work together. Their systems-thinking approach identifies intersecting stakeholder interests, resolves conflicts early, and establishes clear engagement rules to prevent power imbalances. They also design governance structures that align multi-stakeholder efforts with ESG goals, ensuring that collaboration leads to measurable environmental and social outcomes rather than just discussions.

Ultimately, the most impactful collaborations don’t rely on a single framework. Instead, they adapt and integrate approaches as challenges evolve. By blending MSPs, governance models, and co-design methods, organizations can bridge coordination gaps, address power dynamics, and deliver community-centered solutions. Whether working across jurisdictions, forming business coalitions, or co-creating with local communities, success hinges on intentional design that prioritizes inclusion, adaptive learning, and shared accountability from the outset.

FAQs

How do Multi-Stakeholder Platforms resolve conflicts among participants with differing perspectives?

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) play a critical role in resolving conflicts by promoting open dialogue, encouraging transparency, and working toward shared objectives. They provide an inclusive environment where every participant has the opportunity to contribute, fostering mutual understanding and building trust among diverse stakeholders.

When disagreements arise, MSPs rely on collaborative problem-solving strategies. These may include addressing power imbalances, facilitating mediation, and focusing on solutions that reflect the collective interests of the group. This approach ensures decisions are equitable, widely supported, and geared toward achieving lasting cooperation and consensus.

What are the key challenges in implementing collaboration governance models?

Implementing governance models for collaboration often comes with its own set of challenges. One major hurdle is finding ways to balance the varied interests of stakeholders while addressing uneven power dynamics that might arise. Without careful attention, these issues can lead to friction or misunderstandings.

Another critical element is defining clear roles and responsibilities for all participants. Ambiguity in this area can lead to confusion and inefficiencies, making it harder for the group to function effectively.

Equally important is maintaining open communication channels and building trust and commitment among all parties over time. These aspects require consistent effort and thoughtful planning to ensure the collaboration stays productive and fair for everyone involved.

How do Co-Design Frameworks promote inclusivity and address power dynamics?

Co-Design Frameworks are all about bringing people together and making sure everyone has a say in the decision-making process. They provide a platform where individuals from different backgrounds, experiences, and levels of influence can actively participate and share their insights.

By focusing on openness and shared responsibility, these frameworks help establish trust and give a louder voice to those who might otherwise be overlooked or marginalized. This method ensures that the final outcomes incorporate a variety of viewpoints and address the needs of the whole group, balancing power dynamics and encouraging fair participation.

Related Blog Posts

FAQ

01

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

02

What makes Council Fire different?

03

Who does Council Fire you work with?

04

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

05

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

06

How does Council Fire define and measure success?

Dec 19, 2025

Frameworks for Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

Sustainability Strategy

In This Article

Explores MSPs, governance models, and co-design methods for inclusive, scalable multi-stakeholder collaboration—trade-offs, conflict resolution, and integration strategies.

Frameworks for Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

In addressing complex sustainability challenges like climate adaptation, resource management, and infrastructure resilience, collaboration among diverse stakeholders is essential. This article explores three key frameworks that facilitate such partnerships:

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs): These platforms bring together varied groups for structured dialogue, using participatory tools to align efforts and address shared concerns. MSPs emphasize broad representation, conflict management, and scalability but require significant resources and skilled facilitation.

Collaboration Governance Models: These models formalize decision-making, balancing inclusivity and efficiency. They ensure clear roles and conflict-resolution protocols, making them suitable for scaling across sectors, though they can be complex to implement.

Co-Design Frameworks: By involving stakeholders directly in solution development, co-design ensures that lived experiences shape outcomes. This approach fosters shared ownership and addresses power imbalances but demands time, resources, and skilled facilitation.

Each framework has its strengths and trade-offs. MSPs excel in coordination, governance models bring structure, and co-design focuses on tailored solutions. The best results often come from integrating elements of all three, aligning efforts with clear goals and shared accountability.

Multi-Stakeholder Collaboratives - Better Practices for Facilitation and Coordination

1. Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs)

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) bring together a range of stakeholders to tackle sustainability challenges through structured dialogue and collaborative problem-solving. These platforms follow a phased approach - exploration, divergence, co-creation, convergence, and commitment - using various participatory tools to guide discussions and decisions [2].

Inclusiveness

MSPs aim to include diverse voices, particularly those often overlooked or lacking traditional influence. By identifying "hidden" stakeholders, these platforms ensure broader representation. For example, eight landscape-level MSPs across multiple countries have improved stakeholder interactions. In India, block-level MSPs connected villages with government agencies, NGOs, and private sector players to share knowledge on agriculture and resource management [3]. Similarly, initiatives like the Partnership for Global LGBTQI+ Equality highlight how direct engagement of multiple stakeholders fosters more democratic decision-making [5].

"True inclusiveness in multi-stakeholder platforms requires moving from 'giving a seat at the table' to 'sharing the power to set the menu.'" - Council Fire [1]

To level the playing field, effective MSPs often employ neutral third-party facilitators and provide resources like financial stipends, technical support, or translation services to under-resourced groups. Platforms with inclusive governance models are 2.5 times more likely to achieve lasting policy outcomes compared to efforts led by a single sector [1]. However, building trust and fostering inclusivity often require significant upfront time and resources, particularly during the early stages.

Conflict Resolution

Disagreements are inevitable in MSPs, but they are managed through tools like Conflict Styles assessments, Ritual Dissent, and participatory learning events. These methods help stakeholders co-create solutions, prioritize actions, and commit to shared goals. MSPs are especially effective in addressing governance gaps by coordinating efforts across traditionally siloed sectors. For instance, in Oromia, Ethiopia, an MSP aligned NGO activities in rangelands, while in India, block-level platforms revived intercommunity cooperation through conservation planning [3].

Rather than focusing on positions, MSPs emphasize interest-based negotiation, uncovering solutions that address stakeholders' core needs. Joint fact-finding processes also play a crucial role, as stakeholders collectively select experts and define research parameters, creating a shared data foundation and avoiding "expert battles." Around 70% of successful MSPs cite the presence of a neutral backbone organization as essential for maintaining trust among participants [1].

Scalability

MSPs can expand their impact by linking platforms across different levels - such as villages, subdistricts, and beyond - facilitating mutual learning and influencing broader policies. In India, for example, village-level platforms evolved into block-level collaborations, enabling intervillage conservation plans and larger landscape-focused outcomes [3]. This nested governance structure allows MSPs to address large-scale issues while staying connected to local needs.

However, scalability often leads to "coordination fatigue", as the growing number of participants demands more time and resources for consensus-building. Digital tools and phased pilot projects can help MSPs scale effectively while managing these challenges.

Implementation Complexity

Designing and managing MSPs involves navigating distinct phases and employing tailored facilitation tools. For instance, NetMapping and SWOT Analysis support the exploration phase, while Open Space and Visioning techniques aid co-creation [2]. Frameworks like the Cynefin Framework for context analysis and formal Partnership Agreements help reduce complexity.

Power imbalances often complicate MSP operations, making strong facilitation and early governance charters essential. These charters clarify roles and establish conflict-resolution protocols. Additionally, the differing operational rhythms of government, private, and nonprofit sectors - each with its own timelines and success metrics - can hinder unified implementation. Long-term, flexible funding and a dedicated administrative body remain critical but challenging to secure.

MSPs promote inclusive dialogue, resolve conflicts through shared interests, and offer scalable solutions. While their complexity can be daunting, they lay the groundwork for governance models with structured decision-making frameworks, as explored in the following section.

2. Collaboration Governance Models

Collaboration governance models formalize decision-making within multi-stakeholder platforms, ensuring that all voices are heard while maintaining structure. These models can be company-led, involving direct stakeholder participation or advisory councils, or they can be multi-stakeholder, with either direct or representative participation [5].

Inclusiveness

The degree of inclusiveness hinges on whether decision-making is company-led or multi-stakeholder. In multi-stakeholder models with direct participation, like The Partnership for Global LGBTQI+ Equality, all involved parties - companies, NGOs, and governments - have formal decision-making authority to represent their interests directly [5]. Advisory models, in contrast, allow stakeholders to provide input while the company retains ultimate decision-making power.

To balance inclusiveness with efficiency, effective models use transparent representation criteria. Tools such as the Power-Interest Grid and tiered governance structures help ensure fair representation [5][6][3].

"Effective governance in multi-stakeholder environments is about creating a 'container' where conflict can be productive rather than destructive." - Council Fire [1]

Inclusiveness often requires dedicated resources. For instance, Collective Impact initiatives typically allocate 5%–15% of their total budget to governance functions, providing the administrative and technical support smaller organizations need to participate equitably. Some models even offer participation offsets, such as stipends for community members or technical assistance for smaller NGOs, to lower barriers to entry.

Once representation is established, formal conflict-resolution mechanisms are critical to sustaining collective progress.

Conflict Resolution

Formal conflict-resolution mechanisms, including conflict-style assessments, adaptive dialogue, and structured escalation processes, help shift focus from individual positions to shared interests, encouraging creative, consensus-driven solutions [2][3][9]. In company-led models, conflicts are often handled internally with minimal external involvement. Multi-stakeholder models, however, require structured negotiations among all decision-makers.

Platforms with written conflict-resolution protocols are 40% more likely to achieve long-term success than those relying on informal agreements [3]. A notable example is the Oromia MSP in Ethiopia, which addressed governance gaps by coordinating NGO activities across sectors with transparent conflict-management processes. Consent-based decision-making - where proposals move forward unless there are "paramount objections" - offers a balanced approach between full consensus and majority rule.

Scalability

Multi-stakeholder models with representative participation are well-suited for scaling by linking governance across different levels. In India, for instance, village-level platforms have evolved into block-level collaborations, enabling coordination across villages for broader conservation and landscape management through clear communication channels [3]. This nested governance structure allows local groups to contribute to regional or national steering bodies.

Company-led models, on the other hand, often face challenges in scaling beyond corporate networks due to their narrower stakeholder engagement. As collaborations expand, decision-making tends to shift from direct participation to representative systems, where stakeholder categories elect spokespeople to streamline coordination.

Tying scalability to established institutions, such as municipal councils or river-basin authorities, enhances legitimacy and reduces redundancy [3][7][8]. Digital governance tools, like asynchronous decision-making platforms, are also increasingly used to address time zone and resource challenges.

Implementation Complexity

Multi-stakeholder models demand skilled facilitation, clear processes, and written agreements to manage the diverse priorities of participating organizations. Allocating budgets for facilitation and monitoring can reduce friction and improve clarity [2][1]. For example, BSR's framework helped one partner group transition to a multi-stakeholder representative model by balancing democratic decision-making with manageable complexity [5].

"Governance is not just about who makes the decisions, but how the information flows to those decisions to ensure no stakeholder is left in the dark." - Council Fire [1]

The success of implementation depends on aligning the governance structure with the issue at hand. High-stakes or politically sensitive challenges often necessitate robust, inclusive governance, even if it slows decision-making. Conversely, technical issues with narrower scopes may benefit from lighter structures. Written agreements outlining mandates, roles, decision rules, and review cycles can help reduce ambiguity, while dedicated budgets address recurring costs - an area many collaborations underestimate. A survey of over 100 global partnerships revealed that 65% of participants identified unclear governance as the main reason for stakeholder withdrawal [1].

This structured approach to decision-making sets the stage for the co-design frameworks that follow, where stakeholders work together to develop solutions.

3. Co-Design Frameworks

Co-design frameworks redefine the role of stakeholders, turning them into active collaborators who help identify problems and craft solutions throughout the project lifecycle. Instead of experts designing for communities or organizations, this approach values lived experiences as much as technical expertise, ensuring that those most impacted by a challenge play a central role in shaping the response. Using the Double Diamond process - discovery, definition, development, and delivery - co-design integrates stakeholders directly into the solution-building process, complementing multi-stakeholder partnerships (MSPs) and governance models.

Inclusiveness

One of the strengths of co-design lies in its ability to address power imbalances intentionally. A 2022 UK study highlighted this, showing how the involvement of 50 diverse stakeholders resulted in a well-validated whole-school physical activity framework [4]. Successful co-design begins with power mapping to identify decision-makers and marginalized groups, followed by deliberate efforts to amplify underrepresented voices. Strategies include equitable compensation, plain-language communication, and accessible meeting formats.

"To create lasting change, we must move from designing for people to designing with them." - Council Fire [1]

Economic barriers must also be addressed. Providing compensation, childcare stipends, transportation support, and flexible meeting times can make participation more accessible. When participants see how their input shapes the design through iterative feedback loops, trust grows, and long-term engagement becomes achievable. With inclusiveness secured, co-design can transform potential conflicts into opportunities for creative problem-solving.

Conflict Resolution

Co-design reframes conflicts by focusing on ideas rather than individuals, using tools like rapid prototyping. The Double Diamond’s structured phases of divergence and convergence allow stakeholders to express disagreements, challenge assumptions, and explore trade-offs in a safe environment. For instance, in the UK whole-school framework project, multiple rounds of divergent brainstorming followed by convergent refinement enabled participants to overcome differences and co-create a solution no single group could have developed alone [4].

Interest-based negotiation is a key element here. Facilitators guide participants to explore why they want something, uncovering shared interests that lead to creative compromises. Neutral facilitation ensures that discussions remain productive and that no single voice dominates. Organizations like Council Fire support this process by combining tools such as joint fact-finding, multi-criteria decision analysis, and structured dialogue to help stakeholders reconcile competing environmental, social, and financial goals.

Scalability

Co-design frameworks can scale effectively when built on flexible processes and cross-scale learning rather than rigid templates. For example, the whole-school physical activity framework used a six-phase Double Diamond approach, maintaining core stages - discover, define, develop, deliver - while allowing local stakeholders to adapt activities and priorities to their specific needs [4]. Research shows that linking local co-design efforts across scales, from community to state levels, can influence broader policy and investment decisions while retaining local relevance.

As projects grow, scalability often requires shifting from intensive direct participation, like full-stakeholder workshops, to representative participation or digital collaboration platforms. Standardized toolkits, facilitation guides, and shared metrics can help regional or local teams replicate the process while maintaining feedback loops to share lessons learned. However, this modular approach must account for context-specific factors like regulatory requirements, local governance norms, and sector-specific challenges, such as U.S. public notice rules or tribal sovereignty considerations.

While scalability offers opportunities, it also introduces complexities that require careful coordination.

Implementation Complexity

Co-design processes demand significant time, resources, and skilled facilitation. For instance, the UK whole-school framework required six distinct phases involving 50 participants across workshops, online revisions, and iterative voting cycles - a timeline spanning months, not weeks [4]. Costs include professional facilitation, outreach, venue logistics, materials, data collection, and participant compensation. While these expenses may exceed those of traditional top-down planning, they can help prevent costly implementation failures later.

Skilled facilitators are essential to manage group dynamics, resolve conflicts, and address power imbalances. Aligning multiple organizations’ legal and accountability structures adds further complexity, especially when public agencies and private firms must integrate co-designed outcomes into official plans and budgets. Organizations can navigate these challenges by defining clear phases, allocating multi-year budgets, partnering with experienced intermediaries - like universities, consultancies such as Council Fire, or NGOs - and testing frameworks through phased pilots before scaling up. Despite these hurdles, co-design turns top-down interventions into collaborative solutions, revealing system-wide connections and paving the way for meaningful change.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Comparison of Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration Frameworks: Strengths and Trade-offs

This section provides a concise overview of the key strengths and limitations of the frameworks discussed earlier, helping organizations weigh their options and make informed decisions based on their unique goals and circumstances.

Each framework brings its own set of benefits and challenges, offering different approaches to tackling complex issues. By understanding these trade-offs, organizations can better align their strategies with their specific needs.

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) are known for their inclusiveness, as they bring together a wide range of participants from government, businesses, and civil society to address multifaceted problems. A study of eight MSPs across seven countries revealed positive results in fostering inclusion, collaboration, and trust-building [3]. However, they come with high implementation complexity, requiring skilled facilitation and a phased approach [2]. Their scalability depends on forming effective cross-scale linkages [3]. While they encourage dialogue and trust, conflict resolution tends to be moderate, as these processes take time [3].

Collaboration Governance Models shine in conflict resolution, thanks to structured decision-making processes that clearly define roles and protocols [5]. These models also offer high scalability, as their flexible structures can expand across various sectors [5]. Their inclusiveness varies from moderate to high, depending on whether they rely on direct participation or representative committees [5]. The primary challenge is moderate implementation complexity, especially when transitioning from corporate-led to multi-stakeholder governance, which requires balancing control between companies and stakeholders [5].

Co-Design Frameworks excel in both inclusiveness and conflict resolution. For example, a UK initiative involving 50 stakeholders - ranging from headteachers to researchers - developed a whole-school physical activity framework through mixed-group workshops and iterative voting [4]. This process demonstrated the effectiveness of collaborative refinement, with one draft receiving the highest votes across nine stakeholder groups [4]. These frameworks also support scalability by using adaptive subsystems and driving systemic change [4]. However, they involve high implementation complexity, requiring iterative, multi-phase workshops [4].

Framework | Inclusiveness | Conflict Resolution | Scalability | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms | Moderate (adaptive dialogue needed) [3] | Moderate (cross-scale linkages key) [3] | High (facilitation skills, multi-phase approach) [2] | |

Collaboration Governance Models | Moderate-High (direct/representative participation) [5] | High (structured decision-making) [5] | High (flexible models) [5] | Moderate (depends on leadership shift) [5] |

Co-Design Frameworks | High (mixed-group voting) [4] | High (iterative phases) [4] | High (adaptive subsystems) [4] | High (multi-phase workshops) [4] |

Conclusion

When tackling challenges in multi-stakeholder collaboration, choosing the right framework is essential for success. The choice should be guided by the specific issue at hand. For example, Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) are ideal when the main challenge lies in fragmented authority or coordination gaps. Collaboration Governance Models excel when decision-making processes and power-sharing need clarity, particularly in business-led sustainability initiatives or public-private partnerships. Meanwhile, Co-Design Frameworks work best for creating tailored solutions with direct input from the individuals or groups who will use them.

Each framework offers distinct strengths and trade-offs. MSPs foster dialogue in previously disconnected spaces but often progress slowly. Governance models bring structure and scalability but can lead to power imbalances if not carefully constructed. Co-design, while rooted in lived experiences and fostering shared ownership, demands significant time and resources. Despite these differences, all three frameworks aim to streamline decision-making, promote collaborative ownership, and deliver measurable environmental and social benefits.

To make the best choice, organizations should ask three key questions: What’s the primary challenge - coordination, governance, or solution design? What’s the biggest risk - legitimacy, feasibility, or quality? And, what resources - budget and time - are available? Often, the most effective approach combines elements of all three frameworks: MSPs to create a platform for dialogue, governance models to define roles and responsibilities, and co-design methods for focused, actionable solutions.

Council Fire exemplifies how these frameworks can work together. Their systems-thinking approach identifies intersecting stakeholder interests, resolves conflicts early, and establishes clear engagement rules to prevent power imbalances. They also design governance structures that align multi-stakeholder efforts with ESG goals, ensuring that collaboration leads to measurable environmental and social outcomes rather than just discussions.

Ultimately, the most impactful collaborations don’t rely on a single framework. Instead, they adapt and integrate approaches as challenges evolve. By blending MSPs, governance models, and co-design methods, organizations can bridge coordination gaps, address power dynamics, and deliver community-centered solutions. Whether working across jurisdictions, forming business coalitions, or co-creating with local communities, success hinges on intentional design that prioritizes inclusion, adaptive learning, and shared accountability from the outset.

FAQs

How do Multi-Stakeholder Platforms resolve conflicts among participants with differing perspectives?

Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) play a critical role in resolving conflicts by promoting open dialogue, encouraging transparency, and working toward shared objectives. They provide an inclusive environment where every participant has the opportunity to contribute, fostering mutual understanding and building trust among diverse stakeholders.

When disagreements arise, MSPs rely on collaborative problem-solving strategies. These may include addressing power imbalances, facilitating mediation, and focusing on solutions that reflect the collective interests of the group. This approach ensures decisions are equitable, widely supported, and geared toward achieving lasting cooperation and consensus.

What are the key challenges in implementing collaboration governance models?

Implementing governance models for collaboration often comes with its own set of challenges. One major hurdle is finding ways to balance the varied interests of stakeholders while addressing uneven power dynamics that might arise. Without careful attention, these issues can lead to friction or misunderstandings.

Another critical element is defining clear roles and responsibilities for all participants. Ambiguity in this area can lead to confusion and inefficiencies, making it harder for the group to function effectively.

Equally important is maintaining open communication channels and building trust and commitment among all parties over time. These aspects require consistent effort and thoughtful planning to ensure the collaboration stays productive and fair for everyone involved.

How do Co-Design Frameworks promote inclusivity and address power dynamics?

Co-Design Frameworks are all about bringing people together and making sure everyone has a say in the decision-making process. They provide a platform where individuals from different backgrounds, experiences, and levels of influence can actively participate and share their insights.

By focusing on openness and shared responsibility, these frameworks help establish trust and give a louder voice to those who might otherwise be overlooked or marginalized. This method ensures that the final outcomes incorporate a variety of viewpoints and address the needs of the whole group, balancing power dynamics and encouraging fair participation.

Related Blog Posts

FAQ

What does it really mean to “redefine profit”?

What makes Council Fire different?

Who does Council Fire you work with?

What does working with Council Fire actually look like?

How does Council Fire help organizations turn big goals into action?

How does Council Fire define and measure success?